When Russia tried to influence the 2016 U.S. presidential election, it set off what appeared to be a reckoning with foreign disinformation campaigns in the United States.

Government investigations found that Russian hackers had penetrated the inboxes of the Democratic National Committee and the campaign chairman for presidential nominee Hillary Clinton and released internal documents. A Russian “troll factory” created thousands of social media accounts it used to interact with Americans and shape political discourse.

The Russian government had attempted to undermine Clinton’s candidacy and boost her opponent Donald Trump, the U.S. intelligence community concluded.

Words like “disinformation” became common parlance in American politics. There were calls for social media companies to take action against weaponized falsehoods online.

Eight years later, as Americans prepare to select their president for the next four years in November, some experts believe the U.S. is no better positioned to block disinformation than it was in 2016.

They say that the problem has grown bigger, politics has entered discussions of disinformation, and social media companies are increasingly backing off content moderation.

“There is a real fear that we could go back to a situation like 2016, where you could have real interference from trolls, from foreign interference in these platforms,” said Shilpa Kannan, a former content curation lead at Twitter (now rebranded as X). “And a lot of voters get their news from these platforms.”

But as with many hot-button issues in the United States, not everyone agrees that disinformation actually threatens the country.

Changing environment

As the presidential primaries kick off, Americans are sharply divided.

Polling suggests almost a third incorrectly believe that the 2020 presidential race was marred by fraud. Former President Donald Trump — who lost that vote and, according to polls, will likely be this year’s Republican nominee — has actively pushed that narrative.

On Jan. 6, 2021, a group of his supporters stormed the U.S. Capitol in an attempt to stop the ratification of the 2020 results, an event whose interpretation still divides the American public.

Domestically, conspiracy theories, falsehoods, and aggressive statements have become more commonplace in mainstream American politics, said Sara Aniano, a disinformation researcher at the Anti-Defamation League.

The so-called “Overton window,” which describes the range of politically acceptable policy options, shifted in 2016, she told VOA. “Since then,” she said, “we’ve witnessed the normalization of some really nasty rhetoric and false narratives.”

Abroad, the United States faces rivals who may want to influence the vote’s outcome.

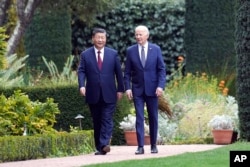

That danger appears to be on the White House’s radar. In November, President Joe Biden raised the issue with Chinese President Xi Jinping and got assurances from him that Beijing would not interfere in the 2024 election, CNN reported.

In cyberspace and the world of technology, the environment is also changing.

The U.S. Cybersecurity & Infrastructure Security Agency has raised concerns that rapidly developing generative artificial intelligence could “amplify existing risks to election infrastructure.”

Meanwhile, social media companies are rolling back efforts to moderate the information shared on their platforms, according to media nonprofit Free Press.

This has “created a toxic online environment that is vulnerable to exploitation from anti-democracy forces, white supremacists and other bad actors,” the organization said in a December report.

While this change in moderation policies is sometimes ideological — Elon Musk, the owner of X, has publicly advocated for fewer restrictions on speech — it’s more often economic.

Starting last year, tech companies laid off over 200,000 employees, including those responsible for content moderation.

Politics gets involved

But as the threat of disinformation has received more attention, it has also become increasingly politicized.

In 2022, the Biden administration launched the Disinformation Governance Board, an entity under the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) tasked with coordinating the department’s efforts to counteract misleading or false information online.

The creation of the otherwise obscure government entity proved extremely controversial.

Top Republicans on the Homeland Security and House Intelligence committees wrote to DHS demanding more information on the little-known, new entity. Senator Mitt Romney, a Republican from Utah, said the board’s creation “communicates to the world that we’re going to be spreading propaganda within our country.”

Senator Josh Hawley, a Republican from Missouri, tweeted that “Homeland Security has decided to make policing Americans’ speech its top priority.”

Nina Jankowicz, the disinformation expert chosen to lead the board, denies that its purpose was to censor Americans. Amid the controversy, she said she faced a wave of harassment and even death threats.

After just a few weeks on the board, she resigned. The board was later dissolved.

Since then, the subject of disinformation has remained controversial. In February 2023, the Republican-led House Judiciary Committee subpoenaed documents from five major tech companies as part of an investigation into whether they had colluded with the Biden administration to censor conservative speech.

It’s not just elected leaders who are concerned about how the government and social media companies choose to address disinformation.

Jankowicz believes the intrusion of partisan politics into efforts to prevent the spread of disinformation makes it harder for social media companies to moderate false and toxic content.

“They’re being disincentivized from doing the right thing,” she said.

But Aaron Terr, the director of public advocacy at the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression (FIRE), a nonpartisan civil liberties organization, disagrees.

He believes that, if the government is empowered to battle disinformation, politicians may deem ideas they disagree with as falsehoods and move to purge them from the public discourse. That would have a chilling effect on public debate, he told Voice of America.

“Whatever concerns exist about misinformation, there’s no reason to believe that it justifies rolling back our basic civil liberties,” Terr said.

Social media speaks

Just as the First Amendment guarantees Americans’ right to free speech, it also guarantees social media companies’ right to exercise editorial discretion.

They say they are doing just that and disagree with the assessment that they have thrown in the towel on counteracting disinformation.

VOA reached out for comment to four major social media companies: Meta (Facebook, Instagram), YouTube, TikTok and X. With the exception of X, which usually does not respond to press inquiries, all answered and outlined their strategies for fighting falsehoods.

“We’ve heavily invested in the policies and systems that connect people to high-quality election content,” Ivy Choi, a spokesperson for YouTube, said in an email. “Content misleading voters on how to vote or encouraging interference in the democratic process is prohibited, and we rigorously enforce our Community Guidelines, which apply for all types of content, including elections.”

While YouTube has previously faced criticism for an algorithm that can recommend increasingly extreme content to users, the company denies that it works that way. Choi told VOA that the platform’s recommendation system “prominently surfaces election news and information from authoritative sources.”

“Our commitment to supporting the 2024 election is steadfast, and our elections-focused teams remain vigilant,” she said.

Meta directed VOA to a publication outlining its efforts to counteract election disinformation.

“We have around 40,000 people working on safety and security, with more than $20 billion invested in teams and technology in this area since 2016,” the company wrote in that document. “While much of our approach has remained consistent for some time, we’re continually adapting to ensure we are on top of new challenges, including the use of AI.”

The company also highlighted its transparency policies surrounding political ads. Meta will block new political and social ads during the final week of the presidential campaign. It also now requires advertisers to disclose when they use AI to alter realistic images, video or audio in a political ad.

Although X did not respond to VOA’s request for comment, the company has previously said it is updating its policies during the election to prevent content that “could intimidate or deceive people into surrendering their right to participate in a civic process.” It characterizes its approach to harmful content as “freedom of speech, not reach” — meaning X will not necessarily take down posts that violate its terms of service, but will limit their visibility and publicly label them.

Of all the social media platforms, TikTok is the wildcard. The app only arrived in the United States after the 2016 election. Since then, its popularity has skyrocketed, particularly among young people. The U.S. government has contemplated banning the Chinese-owned app over national security concerns.

Unlike other social media, TikTok bans political ads. A spokesperson said the company does not allow misinformation about civic and electoral processes and removes it from the platform. TikTok also works with fact checkers to assess the accuracy of content and directs users to trusted voting information. The platform prohibits AI-generated content of politicians and requires creators to label realistic AI-generated content, the spokesperson added.

But is it enough?

Former Twitter employee Kannan worries it’s not — “especially in a crucial year like 2024, when billions of people are going to vote,” she said.

Meanwhile, other Americans fear that free political debate might get lost in the struggle against intentional falsehoods.