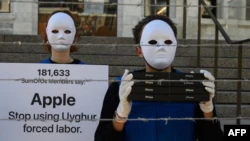

The Chinese Foreign Ministry reacted angrily on Thursday to the announcement that, later this month, the Biden administration will begin enforcing a new law barring products made with forced labor in China’s Xinjiang province from being imported to the United States.

The Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act (UFLPA), which President Joe Biden signed into law in December, is set to take effect June 21. Under the law, U.S. Customs and Border Protection will treat any goods that are made in Xinjiang, either wholly or in part, as the product of forced labor unless the importer can show “clear and convincing evidence” that they are not.

The law passed with strong bipartisan support, as lawmakers from both parties joined to condemn China’s treatment of its Uyghur Muslim minority. The U.S., Canada, the United Kingdom, the Netherlands and an array of human rights groups have accused China of perpetrating genocide against Uyghurs, with a regime that includes mass imprisonment and forced labor, vast “reeducation” camps, forced sterilization, blanket surveillance and the separation of children from families.

China reacts

China has denied the allegations against it in forceful terms, and Foreign Ministry spokesperson Zhao Lijian repeated those denials Thursday when he condemned the U.S. announcement that the UFLPA would soon come into force.

“We have rebuked U.S. lies on Xinjiang many times,” he said at a news conference. “The so-called Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act, in disregard of facts, maliciously smears the human rights conditions in China’s Xinjiang, grossly interferes in China’s internal affairs, gravely violates international law and basic norms governing international relations, and violates market rules and commercial ethics.”

Zhao warned of dire consequences that, he said, would follow from the law’s being allowed to take effect.

“If implemented, the act will seriously disrupt normal cooperation between Chinese and American businesses, undermine the stability of global supply chains and eventually hurt the U.S.’s own interests,” he said. “We urge the U.S. to refrain from enforcing the act, stop using Xinjiang-related issues to interfere in China’s internal affairs and contain China’s development. If the U.S. is bent on doing so, China will take forceful measures to firmly defend its own interests and dignity.”

China’s potential response

The Biden administration has given no indication that it would consider seeing the law go unenforced. On Wednesday, in a webinar about the new law, a Customs and Border Protection official said, “The expectation is that we will be ready to implement the Uyghur Act on June 21, and that we have the resources.”

How China will respond is not immediately obvious, but some sort of reaction is almost certain, said Marcus Noland, executive vice president and director of studies at the Peterson Institute for International Economics.

“The Chinese play hardball,” Noland told VOA. “They use what you might call legal means, they abuse legal means, and they use extralegal means in terms of economic coercion or retaliation, oftentimes linked to noneconomic issues.”

In the past, he said, Beijing has used “anti-dumping” sanctions to retaliate for what it has seen as political slights. For example, it imposed sanctions on Australian barley, beef and wine in what was widely seen as retaliation over an Australian call to probe the origins of COVID-19 on mainland China. Beijing restricted imports of Norwegian salmon after the Nobel Committee gave the Nobel Peace Prize to Chinese dissident Liu Xiao Bao.

Noland said the U.S. might see those types of retaliatory sanctions. However, he said, Beijing might resort to something more complex, such as demanding that Chinese firms break the embargoes the U.S. and its allies have imposed on Russia for the invasion of Ukraine.

US businesses concerned

U.S. companies that do business in China are concerned about the looming implementation of the UFLPA, said Doug Barry, a vice president with the U.S.-China Business Council, in an email exchange with VOA.

The law creates what is known as a “rebuttable presumption” that goods with ties to Xinjiang were produced with forced labor. This means that unless an importer can prove to the satisfaction of Customs and Border Protection that the goods are not made with forced labor, they will be subject to seizure, forfeiture, fines and other penalties.

This creates “a high bar” for importers to clear, Barry said, and the rules importers must observe remain in question.

“The specifics of what must be proven and how have not been announced, leaving American companies to worry that cargo may be seized for unspecified reasons,” he said. “Companies insist that they take every reasonable action to ensure supply chains don’t involve forced labor. The worry is that the law is so broad that it can apply to many categories of goods regardless of proximity to Xinjiang.”

The uncertainty is made worse by what Barry described as the “amped-up rhetoric” coming from both Washington and Beijing.

“In the absence of official dialogue, [it] makes it difficult to put a floor under the downward trajectory of the bilateral relationship.”

Labor investigation demanded

Also on Thursday, the United States, Canada, the U.K., Australia and the European Union asked the International Labor Organization, an arm of the United Nations, to launch a probe into whether China is abiding by its commitments to international labor conventions that Beijing has ratified.

The countries cited reports of mistreatment of Uyghurs in Xinjiang in general, and of prisoners being subject to forced labor in particular.

“We call on the PRC to immediately end its discriminatory policies and abuses against minority groups,” U.S. Ambassador to the U.N. in Geneva Sheba Crocker said in a statement.

Crocker called on China to “provide full and unhindered access, including meaningful, unrestricted and unsupervised access to all relevant organizations, individuals and locations implicated in the system of detention.”

A Chinese representative to the U.N. in Geneva denied the allegations, calling them “a political show.”