China wants stabilized relations with the United States in the short term as it faces domestic economic challenges and pushback in Asia to its assertive diplomacy, White House Indo-Pacific coordinator Kurt Campbell said on Thursday.

Frustrations over China’s strict COVID-19 protocols boiled over into widespread protests last month, the biggest show of public discontent since President Xi Jinping came to power in 2012. The rules had contributed to a slowing economy, but the recent easing of restrictions has also created fresh concern that the virus could soon run wild.

Campbell said those issues, coupled with the fact that China had antagonized many of its neighbors, meant it was interested in more predictable ties with Washington in the “short term.”

“They’ve taken on and challenged many countries simultaneously,” Campbell told an Aspen Security Forum event in Washington, mentioning Chinese territorial disputes with Japan and India. “I think they recognize that that has, in many respects, backfired.”

“All of that suggests to me that the last thing the Chinese need right now is an openly hostile relationship with the United States. They want a degree of predictability and stability, and we seek that as well,” Campbell said.

In the next several months, Campbell said, the world would see “a resumption of some of the more practical, predictable elements of great-power diplomacy” between Washington and Beijing.

“I think we’re going to see some developments that I believe will be reassuring to the region as a whole,” he said without elaborating.

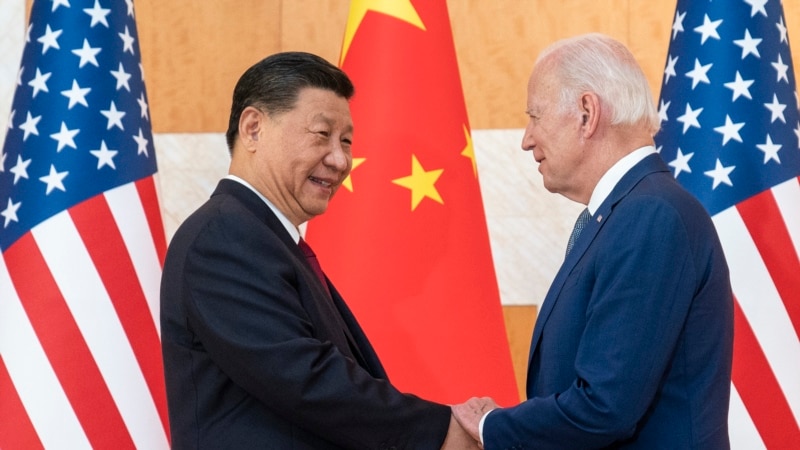

Campbell’s remarks came after a first face-to-face meeting as leaders between Xi Jinping and President Joe Biden last month and two days after Washington announced plans to step up its rotational military presence in key region ally Australia amid shared concerns about China.

Campbell said Russia’s war in Ukraine had led to more behind-the-scenes discussions in the Indo-Pacific about maintaining peace and stability over Taiwan, the democratically governed island China claims as its territory.

“If there were a challenge, it would have terrible consequences, strategically, commercially, and that is in no one’s interests. And so I think every country understands the delicacy here,” he said.

Separately on Thursday, Ely Ratner, the top Pentagon official for the Indo-Pacific, said 2023 would likely be the most transformative year for U.S. force posture in the region in a generation.

“We are going to be making good on a strategic commitment that people have been looking for for a long time,” Ratner told the American Enterprise Institute, highlighting cooperation with regional allies the Philippines and Australia.

Campbell noted currently limited U.S. diplomatic, intelligence and military capacity in the region and added: “Building that is no small feat. It’s going to take a substantial period of time.”

Australia’s U.S. Ambassador Arthur Sinodinos told another Aspen panel that Japan would also be more involved in future military force posture initiatives in northern Australia.

Australia, Britain and the United States reached a security agreement last year known as AUKUS, which will provide Australia with the technology to deploy nuclear-powered submarines, a deal their defense ministers discussed in Washington this week.

Britain’s Washington envoy Karen Pierce told the Aspen forum there was a risk of miscalculation and misunderstanding with China “because we don’t have quite as many mechanisms as I think we need to be able to deal with whatever might come out of Chinese activity.

“And if you compare that to what we had with the Soviet Union in the Cold War, I think you can see there’s a deficit there,” she said.