Abbott Elementary began its second season on Sept. 21 with an audience in line with its averages for its first season. Still, after a season of critical adoration and just days after two high-profile Emmy victories, the opening numbers on ABC — 2.92 million viewers — could seem underwhelming.

That 2.92 million figure, however, represents only about 42 percent of the people watched the show over its first seven days. Almost as many — just under 2.7 million — watched the Abbott premiere on Hulu or ABC’s streaming app, according to the network. About 1.38 million caught up via Nielsen-measured DVR use.

We’re highlighting Abbott Elementary not because those ratings numbers make it an outlier, but because its performance is pretty typical of a scripted show on a legacy outlet. With streaming now a first (or only) option for a large number of TV users, the ratings landscape has changed significantly even in the three years since THR last broke down the ins and outs of TV measurement.

In analyzing available data and conversations with research and ad sales executives at several media conglomerates, a more complicated picture of just how many people watch a given show — and where and when they choose to watch — emerges. The on-air, first-day viewing that was once the standard for networks and advertisers is now less indicative of success for most programming — sports, other live events and news very much excepted — than it ever has been. Streaming has also extended the life of any given TV episode almost indefinitely, and media companies are measuring (and occasionally touting) those long-tail viewers.

A lot of that data remains shielded from the public, the subject of transactional discussions between ad buyers and sellers or streaming outlets and creators but not generally available for the media and TV watchers to dissect. Netflix has taken a few steps toward transparency, posting weekly lists of its most watched titles online and signing up with Nielsen for measurement of its soon-to-debut ad-supported subscription tier. Amazon, similarly, has been open about its Thursday Night Football viewership, with the games part of Nielsen’s national sample and supplemented with first-party data (though good look finding much from the company about The Lord of the Rings: The Rings of Power). A host of newer analytics companies have also elbowed into the space where Nielsen had a virtual monopoly for decades, meaning that the transactional side of TV measurement is moving more toward a multi-currency model.

Nielsen ratings are, however, still the foundation for the public-facing component of TV measurement on network and cable outlets, along with occasional in-house supplemental data about streaming. From those numbers and what streaming data is out there, it’s possible to come to a decent understanding of how and when people choose to watch.

Same-Day Ratings: The Starting Point

Anyone who watches a show on the night it airs, either live or by 3 a.m. local time the next day — Nielsen’s cutoff point for the 24-hour period — gets counted in same-day ratings. Those people, however, have steadily declined as a percentage of a show’s total audience.

Live sports and news programming are big exceptions to that rule — virtually all the audience for your average NFL or NBA game is there as it airs, and news programming, from 60 Minutes to Hannity, is similar (though magazine shows like ABC’s 20/20 and NBC’s Dateline do get some delayed viewing bump).

There’s some variance within entertainment programming as well. Dramas tend fare best both in same-day and delayed viewing — for the 2022-23 season to date, they take up 12 of the top 20 spots (excluding sports) in same-day viewers and 14 of the top 20 after a week of DVR playback. Comedies, in turn, generally get a bigger bump from delayed viewing than do unscripted shows.

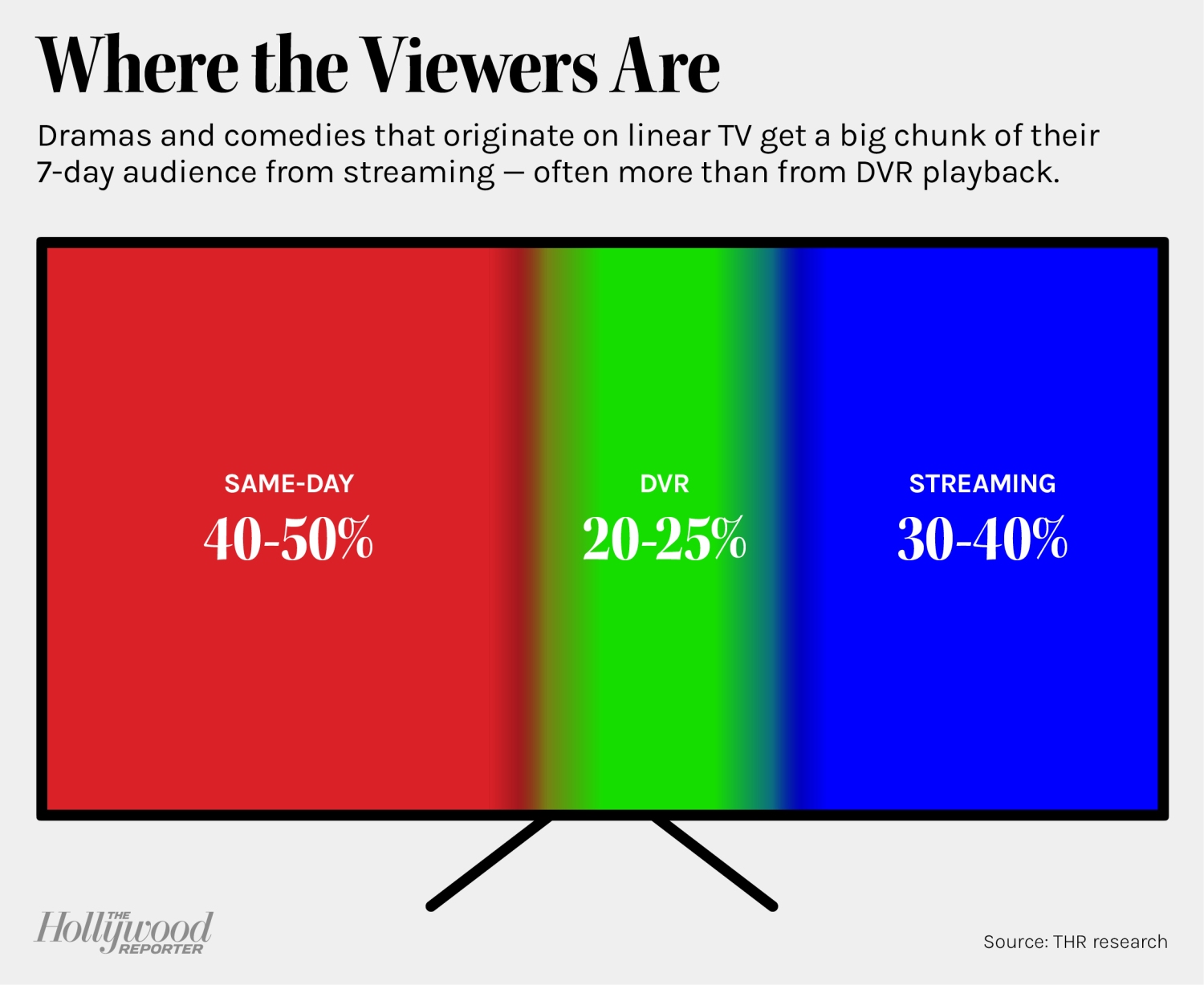

Percentages vary from show to show as well, but most entertainment shows get less than half — somewhere between 40 and 50 percent — of their eventual seven-day audience the night they air. The research and analytics executives THR spoke to for this story confirmed that range for most entertainment programming.

DVR Use: Still a Thing

In the mid-2010s, close to 100 million homes in the United States subscribed to cable or satellite TV service, and the DVRs built into the boxes that delivered those services into homes got a big workout, as they were at the time the primary way for TV watchers to catch up on shows in the days after their on-air runs. In the 2017-18 season, the average broadcast entertainment series added 1.89 million viewers over seven days of delayed viewing; two dozen shows grew by at least 3 million viewers, and nine added 4 million or more.

The number of cable and satellite subscribers has fallen by about 25 million homes since then, according to estimates of the pay-TV universe, which means a similar drop in the number of DVRs in people’s homes. The average seven-day lift has fallen by 29 percent from 2017-18 to 2022-23 — it’s down to 1.31 million viewers. Only three broadcast series grow by as much as 3 million viewers over a week in Nielsen’s seven-day ratings, down from 24 five years ago.

Same-day viewing has fallen even more than the average seven-day lift, however — it’s down by almost a third from 2017-18. As a result, the portion of the seven-day audience from DVR viewing — and not including streaming — has remained consistent: It’s a little under 30 percent for this season and was 29 percent five years ago.

“Not including streaming” is, admittedly, doing a lot of work in that last paragraph. With what streaming data is available (much more on that below), DVR playback shrinks some as a percentage of a show’s cross-platform, seven-day audience, to somewhere around 20 percent to 25 percent.

Streaming: The Great (Mostly) Unknown

Streaming makes up the largest share of TV viewing in the United States. No streaming platform, however, has ever been fully transparent about how many people watch its programming. SVOD services were mostly in a different business — attaining and then keeping the subscribers that make up the “S” in that acronym — than traditional TV outlets and didn’t need to worry about whether, say, enough adults under 50 watched a certain show and saw the commercials targeted to them.

Netflix set the tone at the very beginning of the streaming era by not releasing any concrete viewer data about its early shows like House of Cards and Orange Is the New Black. Other streamers followed suit, and eventually so did media companies that had both linear and streaming outlets.

Netflix has taken a step or two toward more public-facing data with its weekly top 10 charts of the most watched titles on the service by hours viewed — an upsized (and worldwide) spin on Nielsen’s weekly U.S. streaming chart, which measures viewing time in minutes. No other company has really followed suit. Amazon has quietly noted that The Rings of Power racked up some 24 billion minutes, or 400 million hours, of viewing worldwide (at least a third of which, per Nielsen, happened in the United States) and that 100 million people — around half of the 200 million or so Amazon Prime subscribers — watched at least a little of it. Most publicly stated figures from streamers, however, tend to tout percentage increases over “normal” viewing and surges in subscription signups without any baseline for comparison.

It is possible, though, to peek into the black box of streaming viewing data from time to time. The premiere of Game of Thrones prequel House of the Dragon, for instance, had 327 million minutes of streaming time on HBO Max the night of its premiere, according to Nielsen — which works out to an average of just over 5 million HBO Max accounts watching into the 65-minute episode (and, presumably, more than one person watching in some of those 5 million homes). Streaming made up more than half of the total audience for the show’s premiere night.

Circling back to the Abbott Elementary example, ABC said the season two premiere had 7 million cross-platform viewers after a week. The 2.7 million viewers on streaming comes from adding up the same-day viewership and seven-day DVR lift, then subtracting it from the total.

Based on the limited cross-platform data available, the makeup of Abbott’s total audience seems to be fairly representative of other network shows as well: While the majority of the broadcast audience still watches by older means — by turning on the TV at a set time or with a DVR over the next week — streaming makes up 30 to 40 percent (and sometimes more) of a broadcast episode’s seven-day total.

For shows on premium outlets like HBO and Showtime, and even some ad-supported cable channels like FX and AMC, viewing has tilted heavily toward streaming. HBO reported an average of 9 million-plus first night viewers for House of the Dragon during its first season, but under 2 million of those people (1.87 million, to be exact) watched at 9 p.m. on the HBO cable channel. Replays later in the night make up some of the difference, but the large majority of the first night audience — and of the 29 million-viewer average HBO reported over the full 10-week run of the season — watched on HBO Max.

The first season of Showtime’s Yellowjackets averaged 5 million weekly viewers, but only 275,000 were there for the first on-air showing — less than 6 percent of the total. HBO’s Euphoria may be the most extreme example: HBO said its second season averaged better than 16 million viewers over the course of its eight-week run, but just 341,000 watched the first on-air showing each week. That’s barely 2 percent of the total.

The “over the course of its run” figures HBO regularly uses point up another wrinkle in the ratings game: With shows living indefinitely on streaming platforms, their owners can theoretically keep counting viewers forever. It’s debatable how transactionally useful a measure of audience over four weeks (Netflix’s preferred benchmark), five weeks (the basis for “Live +35” ratings broadcasters occasionally tout) or longer might be. But the numbers keep going up with time, which can at least add to the perception of a show being a monster hit.

As for streaming originals, there’s still a relative paucity of data out there. Netflix’s weekly top 10 gives some insight into its global audience, and Nielsen’s rankings do the same — albeit several weeks later — for a number of streamers in the United States. They tend to correlate as well: When Netflix touts massive viewing figures for Stranger Things — 2022’s most watched streaming series — or Wednesday, Nielsen’s data shows a similar picture.

Sonja Flemming/CBS Broadcasting, Inc.; ABC/Richard Cartwright

Both use total viewing time as their favored metric, which tells a different, and differently incomplete, story than the traditional average viewership metric for linear TV. Total time can favor shows whose episodes have longer running times (hello, Stranger Things) or larger libraries. NCIS and Grey’s Anatomy, fixtures in Nielsen’s top 10 acquired series charts, have more than 350 episodes each on Netflix. Even if only a few thousand people are watching a single episode at a given time, that adds up fast when spread across a huge catalog. Original episodes of the two shows on CBS and ABC rack up far more viewers per hour, but since there aren’t nearly as many in a given year, they fall well short of the total time viewers spend with their libraries.

But of course, there are dozens, hundreds, heck, thousands of streaming shows and movies that don’t make the top 10 lists every week. Ted Lasso is the only Apple TV+ series ever to break into the Nielsen chart; If you want to know how big, say, Pachinko or Mythic Quest was, you’re out of luck. The same goes for just about all of Hulu’s FX-produced shows — The Bear did make the rankings for one week over the summer — Disney+ series not affiliated with Marvel or Star Wars and just about every original show on HBO Max and Peacock. In fact, for every series, original or acquired, that made Nielsen’s streaming rankings in 2022 (through mid-November), fewer than 70 spent more than a month in the rankings, and only 15 managed to stick around for three months or more.

TL;DR: It’s Complicated

As the amount of TV programming has exploded in the streaming era, information about who is watching any one of those programs has become scarcer. Unless they’re for live sports or news programming, overnight ratings — the definitive measure of a program’s health little more than a decade ago — tell less than half of the story for most shows. Provided, of course, that a show runs on a platform that still uses overnight ratings. Outside of the most popular handful of titles, precious little information about streaming series ever makes it beyond need-to-know circles within media companies.

The way TV is measured is also changing. As Nielsen faltered during the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic, media conglomerates and ad buyers began to get more aggressive about finding alternative data streams to serve their needs. There’s been a boomlet in TV analytics in the past two years, with companies — among them iSpot, Comscore, VideoAmp, Parrot Analytics and Samba TV — rushing to provide more and different data to media buyers and sellers. Very little of that makes it out for public consumption, but business is being and will be transacted using several different data currencies in the future, the research and ad-sales execs THR spoke to said.

The influx of data means that the research teams at networks and streamers have more information to sift through. Where once there might have been total viewer breakdowns and a couple of demographic subsets — all supplied by Nielsen — to measure the health of a series, now there could be specialized sets of numbers for every aspect of the business.

Still, there are certain figures that research executives go to first. “I look at reach” — the number of people who check out at least a minute or two of a show “because that shows interest,” says Radha Subramanyam, CBS’ chief research and analytics officer. “And I look at time spent because ultimately, that’s engagement. And that determines whether a show is going to have a life.”

Someone focused on ad sales might still be looking at key demographic groups, whether adults 18-49 or 25-54. For Will Somers, executive vp and head of research at Fox Entertainment, it’s a mix of old and new: “We also want to know what’s happening on the many other screens that people have within reach,” he says. “So [in addition to Nielsen ratings] we look at streaming metrics, which we also get on an overnight basis … and try to provide a holistic measure of total audience in real time for our stakeholders.”

The fact that nearly every big streaming service has or is about to have an ad-supported tier will likely increase transparency at least on the transactional side of the business — ad buyers are not in the habit of accepting “trust us” as proof that their messages are reaching the audience they want. But for all the business that gets done with newer ratings currencies, and despite efforts by startups to carve out space, Nielsen is, for now, still the primary provider of public ratings data — however incomplete it may be.

Will that change? It likely will at some point. Everyone with a stake in the game, from ad buyers and network executives to members of the media and interested viewers, would like to have the best numbers at hand. CBS’ Subramanyam was speaking on behalf of her company, but her point can apply across the business: “TV is under-measured and misunderstood. Our programs are among the most viewed in the world and form the backbone of linear and streaming platforms. We hope this becomes clearer as the measurement ecosystem evolves.”