Tucked away inside a nondescript building that serves as the U.S. Secret Service’s Washington headquarters is a museum that most tourists will never get to visit.

“The majority of the audience would be employees, former employees, family and guests, and dignitaries and law enforcement,” says Mike Sampson, an archivist and historian at the U.S. Secret Service, adding that limited resources and security concerns account for the restricted access to the agency’s museum.

The one-room space features artifacts and replicas that showcase the Secret Service’s storied history. The agency is probably best known for protecting American presidents, but its original mission was to fight financial fraud.

Ironically, President Abraham Lincoln authorized the creation of the Secret Service just hours before he was killed.

“On April 14, 1865, the treasury secretary at the time, named Hugh McCulloch, goes to President Lincoln and suggested he create an agency just to fight counterfeiting. At the time, one-third of all the currency in the U.S. during and post-Civil War was counterfeit,” says Jason Kendrick, also an archivist and historian at the U.S. Secret Service. “So, on the same day, he gives verbal authorization — he doesn’t sign anything that actually creates this Secret Service — he’s assassinated at Ford’s Theatre.”

It wasn’t until 1901, after the assassination of President William McKinley, that the Secret Service was officially tasked with protecting the president. But the service’s responsibilities had expanded before then — in part because the FBI and CIA (which serve law enforcement and intelligence functions) had not yet been created.

“Land fraud, stamp fraud, rumrunners, bootleggers,” Kendrick says. “There’s a period where we investigate the Ku Klux Klan, some counterespionage during the Spanish American War, in World War I, and a little bit even during World War II, even after the CIA is created. So, it’s basically, in 1868, upgraded to any crime against the federal government.”

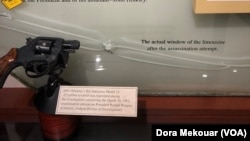

Some exhibits focus on counterfeiting. Others illustrate the dangers of presidential life, such as the window from the armored limousine that was struck by a bullet during the 1981 assassination attempt on President Ronald Reagan. Also on display is the pistol used during the 1975 assassination attempt on President Gerald Ford in San Francisco.

Today, the service continues to protect heads of state, foreign dignitaries and special events related to national security. Its agents are still tasked with safeguarding the U.S. financial system, which includes investigating certain cybercrimes. The agency’s Threat Assessment Center teams with local partners nationwide to help combat school violence and other targeted attacks.

Executing those duties sometimes comes at a terrible price. The museum’s wall of honor pays tribute to the 40 men and women who have died in the line of duty.

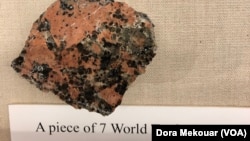

We’ve also been affected by terrorists, and we have artifacts here that recall the bombing in Oklahoma City on April 19, 1995, which we lost six members of our agency in the field office of the Murrah Building in Oklahoma City,” Sampson says. “And we were also affected by September 11. We lost one member of our agency, Special Officer Craig Miller. On September 11, our building was in the second World Trade Center [building] up in New York. So again, it’s a nice area to respectfully honor those folks that have passed.”

And that might ultimately be the point of having a museum that’s only seen by a select few.

“The hall gives us an opportunity to reflect on the history of our agency, and also to show what we’re doing these days,” Sampson says. “We can get a sense, or even a feel, for how we were and how we’ve evolved as an agency, and some of the things that we’re doing today. But it also gives a reflection on how things were at one time.”