“No wonder those four great Americans seem so sad as they look down from Mount Rushmore,” Denver Post columnist Roscoe Fleming wrote in 1962. “For they see incongruous and continuing racism.”

In South Dakota at that time, it wasn’t unusual to see restaurant and shop signs reading, “No Indians Allowed.”

Today, the signs have come down, but VOA has heard from dozens of Native Americans in South Dakota who say that racism permeates their lives and is especially prevalent in the state’s second-largest city, Rapid City.

It was there, as VOA earlier reported, that Gateway Grand Hotel owner Connie Uhre in March announced she would no longer allow Native Americans on the property after a shooting took place there; later, she turned away two members of the Indian-led, nonprofit NDN Collective who tried to book a room at her hotel.

Sunny Red Bear, NDN Collective director of racial equity, is one of the two denied services. NDN Collective, the name a shortening of “Indian,” is an indigenous-led organization in Rapid City that works to empower Native peoples.

“Rapid City, like many places in the U.S., has a long history of racism that many white people are committed to upholding on both a systemic and interpersonal level, whether they know it or not,” she said. “People in positions of power here in Rapid City, by not stating that systemic racism exists in Rapid City, continue to minimize the lived experiences of Native people and people of color here in the community.”

Janet Davies, the daughter of a Lakota mother and a white father, described growing up in a city where she said she was constantly shamed.

“When I was in seventh grade, there was a school dance,” she said. “And this nice boy asked me to go with him. But then later on he said to me, ‘I can’t go with you because I found out you have Indian blood. You’re a sq—w.’”

She used an ethnic and sexual slur for Indigenous women.

In April, during a stay in a Rapid City hospital, Oglala Lakota rights advocate Hermus Bettelyoun posted on Facebook, “I now have a room to myself here. My [white] roommate found out my skin wasn’t the right color tint for him. He asked the doctor if they could move me because he didn’t want to ‘breath the same air’ as [me].”

Native American residents of the city complain of being tailed like thieves in local businesses, being turned down for jobs and enduring taunts to “go back to the reservation.”

“I’ve talked to multiple mothers and fathers whose children are experiencing racism in schools by getting their hair cut by other students, by being called “Prairie N-word,” Red Bear said.

Many expressed conviction that the state government is racist.

Critical race theory

In April, South Dakota Governor Kristie Noem signed an executive order banning the teaching of critical race theory in the state’s primary school system. CRT is an academic theory that states racism isn’t just the product of individual bias or prejudice but is embedded in the nation’s legal systems and policies.

“I think her message to us is that we don’t matter and that the Native experience in South Dakota doesn’t matter,” South Dakota Democratic State Sen. Troy Heinert, a Sicangu Lakota citizen from the Rosebud Reservation, told Native News Online in April.

Red Bear said she views the move as a continuation of historic assimilation policies.

“The lack of education and the lack of conversations around the history of what has happened to Indigenous people are perpetuating crazy, harmful … stereotypes,” Red Bear said.

“I’m fifth-generation Rapid City,” said J.B., who asked VOA to withhold his name out of fear of repercussion. “Up until the George Floyd killing in Minneapolis, I was just another white guy. But when that killing happened, that triggered something in my head. I can tell you Rapid City is on the front lines of a lot of racism right now. It’s called Racist City for a reason.”

Rapid City Mayor Steve Allender admits there is a huge divide between “some of the Native American population here and non-native citizens.”

“If you look back in history and even currently, racism is in all of the continents,” he told VOA. “There’s nothing different or special about Rapid City when it comes to the flaws of humanity.”

“What I think must be pointed out,” he continued, “is that in Rapid City, this takes center stage in the news cycle, whereas there are other parts of the country where this type of stuff [goes on] and the reaction is nowhere near this.”

Historic roots

South Dakota has a history of “tumultuous race relations” dating back to early white settlement, according to a 2019 report by the South Dakota advisory committee to the U.S. Civil Rights Commission.

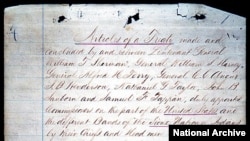

The 1868 Fort Laramie Treaty designated a large territory west of the Missouri River as the exclusive territory of the “Great Sioux” tribes – the Lakota, Dakota and Nakota.

After an 1874 expedition confirmed deposits of gold in the Black Hills, miners flocked to the region. When the Lakota refused to sell mining rights, the government ordered them to reservations and sent in troops when they resisted. The armed conflict that followed saw George Custer’s defeat at Little Big Horn in 1876, the murder of Lakota leader Sitting Bull in 1879 and the massacre of several hundred Indian men, women and children at Wounded Knee.

And, as the South Dakota civil rights advisory committee noted, “overt racism and discrimination continued to impact the indigenous population in South Dakota significantly throughout the twentieth century, and some scholars argue that it manifests itself today in suppressed political participation and disparities in the criminal justice system.”

Native Americans were made citizens in 1924, but South Dakota didn’t allow them to vote or hold office until 1940. Between 1976, when the Voting Rights Act was passed, and 2002, South Dakota passed more than 600 statutes and regulations hindering Native voting in certain jurisdictions with large Native populations.

South Dakota today is home to nine Indian reservations; the 2010 census shows it leads the nation in the percentage of Native Americans living below the poverty line; more than 50% of the Native Americans in Rapid City live in poverty.

Natives invisible

The First Nations Development Institute conducted a two-year nationwide survey on public opinion about Natives. Among their findings:

- Most Americans know Native Americans were oppressed and that their land was stolen but don’t know about the violence involved.

- Non-Natives largely create and control narratives about Native Americans, focusing on deficits such as poverty, alcoholism and ill health.

- Most policymakers and judges have little knowledge of Native issues and do not understand America’s treaty obligations to the tribes, who ceded land to the U.S. in exchange for education, health care, housing and other protections.

- Non-Natives who live near reservations in areas of high unemployment or economic stress may be resentful of these entitlements.

Allender, the Rapid City mayor, said he believes eradicating racism is an unrealistic goal.

“We can certainly reduce it and we can certainly create an environment where these outward manifestations of it are not acceptable,” he added. “I want every citizen, whether a tourist or resident, a white-skinned person, a dark-skinned person … to receive equal treatment, have equal opportunities.”

He expressed frustration over the city’s homeless population.

The city’s annual “point in time” count of the homeless conducted in January showed 458 unhoused adults and children, 350 of whom were Native American. Thirty-nine reported substance abuse, and 28 had serious mental illness.

“Almost all of our homeless people in Rapid City are Native American,” Allender continued. “And a lot of them are intoxicated. And I’ll tell you, the homeless people are a violent group.”

Red Bear, of NDN Collective, is Lakota from the Cheyenne River Sioux Reservation in South Dakota.

“All the talk about our unhoused relatives and that Native people have a predisposition to alcoholism is accompanied by numerous other related misconceptions that feed into the idea that we are morally deficient because of our so-called inability to control ourselves, and that all that makes us a menace to society,” Red Bear said. “These stereotypes are extremely harmful and expose a lack of compassion and empathy for those who are struggling.”

In March, NDN Collective filed a lawsuit against hotel owner Connie Uhre and called for a citywide boycott of businesses with racist policies and practices. South Dakota tribal leaders have suggested they may relocate annual events like the Lakota Nation Invitational Basketball Tournament and Black Hills Powwow, which bring Rapid City millions of dollars in revenue.

The collective said it won’t back down until the city imposes “concrete consequences” on racist business owners.

This has triggered anger among some white citizens.

“Clearly, the Uhre family and their right to engage in commerce have been targeted …for the unpardonable sin of unpopular speech,” one resident wrote to the Rapid City Journal, likening the boycott to “racketeering.”

Mayor Allender also objects to the boycott.

“This hotel is still closed. They probably suffered well into the six figures of economic damage if not more, in the couple of months that they have been closed,” he said, pointing out its irony: “You’re offended because one family judged an entire group of people by the actions of one, and now your response is to judge an entire community because of the actions of one?”