Heading into the summer, entertainment giants Live Nation and MSG Entertainment painted rosy pictures of the live event business, with forecasts of record years of growth. While bookings are on the rise at concert spaces across the U.S., smaller venues are recovering from the impact of the omicron variant, and owners say audiences appear to be cautious to return. There’s also the strain of staffing shortages and the increased cost of goods and labor, plus the lingering question of whether acts will show up.

At First Avenue, which owns and operates several music clubs in Minneapolis, there’s buzz around the “unbelievable” number of artists on the road, due to rescheduled concerts and the delayed return of live events, says CEO Dayna Frank. It’s a prime time to be a concertgoer, but, compared to the surge of customers who returned to venues in July 2021, after COVID-19 vaccines became available, it’s been more of a trickle recently.

“It’s a tough predicament, because on one hand, we’re all happy and celebrating and we’re excited,” says Frank, who is also board president of the National Independent Venue Association, “but on the other hand, there’s so much more to do, and the pain is very real. It’s not recovered, we’re far from it.”

Consumer confidence took a hit at venues after COVID waves in the fall and winter, with First Avenue citing January as the worst month in the company’s history because of the number of show cancellations. Now, things are looking better. But while many shows are technically selling out, venue owners say no-show rates, wherein a customer purchases a ticket but doesn’t attend, remain higher than in 2019.

At the Troubadour in West Hollywood, owner Christine Karayan estimates that attendance is still down 15 percent to 30 percent as a result of no-show customers. The venue is about 50 percent to 60 percent recovered from the pandemic, she says, in terms of revenue and employee retention. No-shows impact small venues because there are fewer people to buy beverages, food or merchandise.

Revolution Hall and Mississippi Studios, concert venues in Portland, Oregon, are seeing no-show rates of 10 percent, which owner Jim Brunburg calls a “thrill” compared to the rates in earlier months. The reasons for not attending vary by customer, but Brunburg surmises that some of it can be traced to patrons testing positive for COVID or feeling hesitant about going to a crowded indoor venue. Demand to play the venues is high, with an average of about seven holds, or requests from bands to perform, per night, Brunburg says.

But venues also are seeing regular cancellations from bands, as members of touring crews contract COVID. Even one canceled or rescheduled concert means no staff members will work that night, and the venue can’t make money. “Many things are making it difficult to run any small business in this country right now, but especially a small business that demands that people be in tight quarters, enjoying each other’s company,” Brunburg notes.

Overall, Revolution Hall and Mississippi Studios are operating at about 60 percent of where they were in 2019, in terms of monthly gross revenue.

To reach this point, many indie venues relied on Shuttered Venue Operators Grants of up to $10 million from the federal government. This money helped venues reopen, rehire staff, make safety improvements to buildings and even weather some of the recent COVID waves. However, the grant money, which must be used by June 30, cannot help business through the unexpected length of the pandemic, says Rev. Moose, executive director of the NIVA. Without the grants, the slim profit margins of the business leave the indie venues vulnerable to new variants that could lead to canceled shows.

Several venue owners mentioned the stress of now being at the center of political debates over vaccination and masking requirements — these vary by state and venue, but can also be set by the performing act. “It is so difficult to be able to compare what is happening now to what happened pre-closure, because the pieces are just moving differently,” Moose adds.

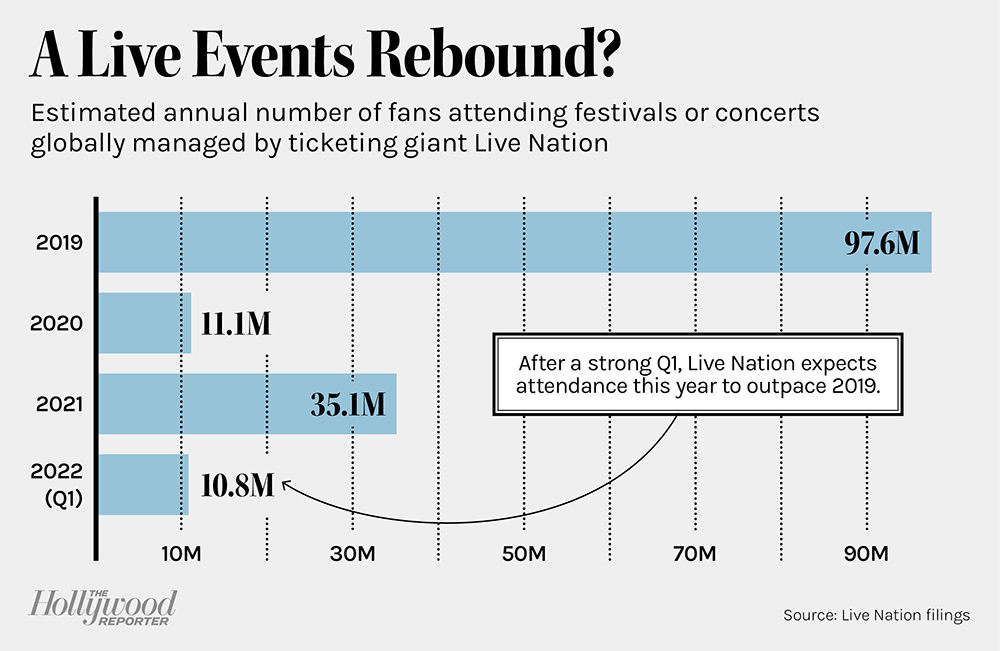

Compared to indie venues, corporate venues have reported less of a continued impact from COVID. In its most recent earnings report, MSG Entertainment, the home of Madison Square Garden, Radio City Music Hall and the Chicago Theatre, among other venues, called the impact of omicron “short-lived,” stating that the number of ticket buyers quickly returned to pre-omicron levels. Live Nation executives said no-show rates at venues had improved or returned to pre-pandemic levels. “All leading indicators point to double-digit growth in fan attendance at our concerts this year relative to 2019,” Michael Rapino, president and chief executive of Live Nation, wrote in the earnings release.

These companies have better profit margins and more diverse offerings than the cash-strapped businesses of independent venues. Still, overall attendance is not back to normal, as Live Nation reported about 11 million fans in the first quarter compared to 15 million in the first quarter of 2019, which executives attributed to a lower planned number of concerts.

Some indie venues also are seeing signs of hope. City Winery, a music and comedy venue in Manhattan, is at about 80 percent of its pre-pandemic revenue, says programming director and NIVA member Grace Blake. The venue relied on an SVOG grant to get through the pandemic and was able to fill slots with local acts and comedians when touring groups canceled due to COVID in December and January.

The older demographic also has been slower to return here, and the no-show rate has leveled off to 10 percent to 15 percent. But Blake is encouraged by the fact that the rate has not increased and patrons are continuing to show up, even during the current COVID wave in New York. “Our falloff is not what we would have expected,” Blake says. “I think people are just ready to hear live music.”

This story first appeared in the June 1 issue of The Hollywood Reporter magazine. Click here to subscribe.