Half Mermaid Productions

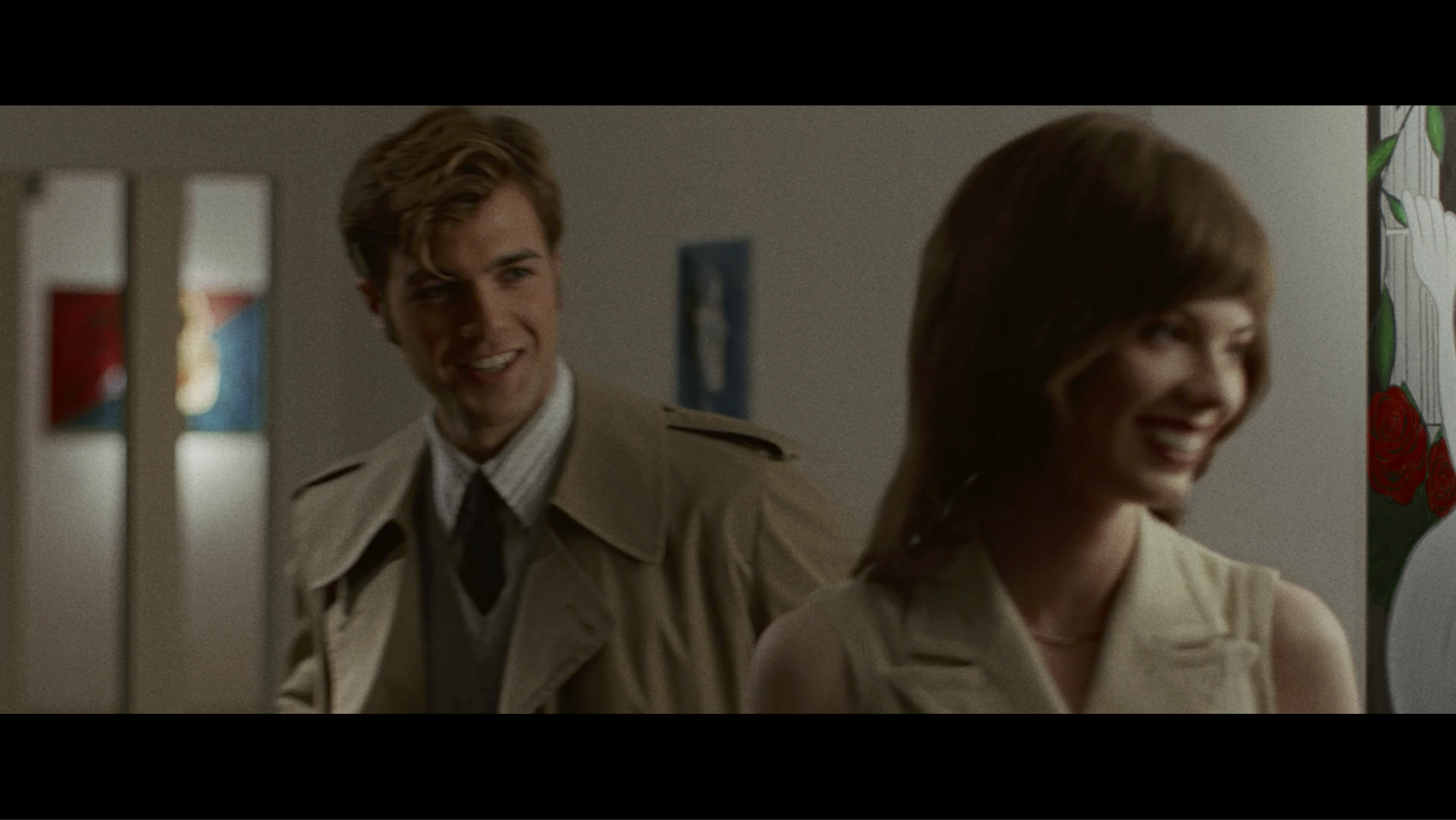

Developer Half Mermaid’s Immortality is a lot of things: ambitious in scope, endlessly playable and eerily mysterious. The game has players sifting through live-action footage from three different films — plus the cast’s behind-the-scenes rehearsals and press junkets, among other surprises — on a playable version of an old Moviola editing bay. Each film is an erotic thriller from a different decade, and the lighting, tone and pace of each project carefully recreate details of each era of cinema. You’re essentially a time-traveling movie detective, with the ability to rewind or fast-forward and zero in on images to match cut to other sequences of footage.

The title, released on Steam in August, was also just released on Android and iOS phones via Netflix Games in mid-November, making it free for Netflix subscribers. It’s been nominated for a slew of end-of-year awards, including Best Game Direction, Best Narrative and Best Performance (for Manon Gage, who plays the eternal actress Marissa Marcel) at the Game Awards.

When asked about the strategy of releasing the title on their platform, a Netflix spokesperson tells THR: “Our vision is to build a library of great games for our 200 million+ members around the world to enjoy. We are focused on providing a variety of games across genres, and on expanding the games catalog by continuing to build and strengthen partnerships with developers around the world of all sizes. We are excited to have Immortality come to Netflix, which is a game rooted in Hollywood history and focused on storytelling.”

A spokesperson for the game’s development team tells THR that the game is on track to be downloaded over a million times on Steam, and players have already racked up over 50 years of playtime.

The game, also available on GOG and XBOX, was developed by Sam Barlow, whose previous titles Her Story and Telling Lies experimented with using surveillance detective-like tools and footage of live-action actors. However, those games were mostly focused on words and information spoken by the actors, which the player could then focus on to parse through other files, data and video containing the same language. Immortality, by contrast, is more streamlined and focused on images and patterns in footage, which the player can click to find similar images in previous inaccessible clips, thus thrusting the story forward. You’ll be going forward and back in cinema history in a nonlinear fashion.

Half Mermaid Productions

“We have this very freeform navigation, where everything is being linked. And you know, there’s no explicit scripting. You click on click on a piece of fruit in this scene, the game is going to look at all the pieces of fruit it has, and it’s going to decide what’s a good piece of fruit to go it,” says Barlow.

Immortality lasers in on specifics of the film industry, highlighting abuse of labor on film sets, deconstructs the myth of the auteur and questions what the purpose of filmmaking in general is. It’s all wrapped up in an endlessly compelling, excitingly nonlinear arrangement of scenes. All the films feature the fictional actress Marcel, and the player must figure out such things as why the three films were never released and why Marcel went missing.

Half Mermaid Productions

Barlow says he was inspired by Rita Hayworth in creating the game. “She was a different woman who was taken in by the studio system, renamed, retrained and physically had her body altered … Hayworth was not the author of her own identity to some extent, but in 2022, Hayworth lives on. People are not talking about the directors and writers and studio executives of those movies.”

The ’70s erotic cop thriller Minsky — one of the three films in the game — features a director passionately talking about authenticity and scouting out real locations for the shoot of his gritty Klute-like thriller. However, the director is also very cozy with his actors and dating Marcel. It’s also clear that he isn’t some singular genius on the production, which is especially evident when an on-set tragedy — similar to the gunshot fired on the set of Rust — occurs.

“I was subscribed to the popular theory that moviemaking in the ’70s was the high point — you had these incredible adult movies that were being made by auteurs who were shooting in a more naturalistic way, and creating these great works of art,” says Barlow. “But if you dig into it, the studio owning Rita Hayworth and creating movies within that system isn’t that different from the auteur director, who is probably sleeping with the actors anyways, and has that additional level of control and power.”

Half Mermaid Productions

“There is obviously a lie that a single individual is authoring the thing, outside of where that is literally the case,” Barlow continues, “The sheer number of people involved, the sheer number of people whose creativity results in the thing on the screen at the end of the day.”

Indeed, Immortality questions the role and value of filmmaking and whether it is worth the torment it inflicts on creators and workers. That there is a resemblance to the incident on the Rust set was coincidental, says Barlow, who had written the scene after being inspired by onset tragedies of The Crow and The Twilight Zone. “It was an additional layer of weirdness seeing the thing that we were trying to plug into unfold in real-time. And having come off of a grueling indie shoot right in the midst of a COVID-surge, and knowing how hard everyone’s working on these indie productions. Safety is always paramount.”

While the game takes inspiration from real-world events, the films within the game also painstakingly recreate the three different eras in which they’re set with startling authenticity. Barlow and his crew recreated lighting and textures of the different eras using old-school lenses and also used various writers to craft each of the three films, though Barlow wrote the connective tissue and meta-narrative that links the stories.

Barry Gifford, the writer of Lost Highway, worked with writer Amelia Gray (Gaslit, Mr. Robot) to adapt a short story of his into another of the game’s movies, the sleazy ’90s neo-noir Two of Everything. Gifford is even featured as a character in the game. (The third film, Ambrosio, is an adaptation by Barlow of the gothic M.G. Lewis novel The Monk).

“We first approached Barry to talk about his work in movies, how it was writing for the screen in the ’90s and the idea of writing for one of our original screenplays. But the more we spoke to Barry, the more it was clear that his voice is so singular and his projects are all very uniquely his, so we came up with the idea of bringing in one of his short stories — one that was very relevant! — and having him adapt that, and it be something that becomes a part of the Immortality world,” says Barlow.

Gifford ultimately declined to play himself in Immortality. “I’m more interested to see somebody who doesn’t know me be Barry Gifford. That makes it a mystery,” he says.

Barlow instructed the screenwriters — Gifford and Gray, along with Allan Scott, who wrote Minsky — not to approach the screenplays as a video game but simply as complete scripts to be filmed. After the scripts were submitted, Barlow assembled the stories into a shooting script and the larger game narrative.

“It was a fun little thing for them because they got to write scripts without any notes or studios,” says Barlow.

Gifford says this is his first time writing for a video game, and that he still has not played it: “Not only had I never written for an interactive game before, I’d never played one and still haven’t. Looking forward to it,” he said. “The closest I’d come was the screenplay for the film Lost Highway — wasn’t that interactive?” he continued.

For his part, Scott — the co-creator of The Queen’s Gambit and writer of such films as The Witches and The Preacher’s Wife — says he wasn’t beholden to telling a story of that era, but rather that he “was indebted to truth, human certainties holding the framework on which we could contain all the variables of real life, real death and real deception.”

He says he was attracted to writing the film for the same reason he adapted the 1973 film Don’t Look Now from Daphne Du Maurier’s novel: “A single explosive event revealing all.”

Gray, who wrote for Barlow’s previous title, Telling Lies, says of working on the screenplay in the dark: “Sam was driving the car and telling me to not worry about where we were going. I still don’t know the full meta-story, by the way. I’m just as excited as everyone else to discover it.”

Barlow is hopeful that players share the same obsessive sense of discovery about exploring all the footage that he does. “I’m probably allied with the kind of Nintendo philosophy that there isn’t necessarily a wrong way to play this game if you’re having fun.”

With more than sixteen hours of gameplay — and long after reaching the “end” of the game — there are still new character arcs, footage and lingering narrative threads to discover in a game that feels like it can last forever, just like the mythologized artform it seeks to recreate.

Says Barlowe of his aim: “Basically, finding a way to encourage people, or giving them the opportunity to be obsessive. And I think I am someone who enjoys being obsessive about a thing.”