Courtesy of AMAZON

PRIME VIDEO

Courtesy of AMAZON

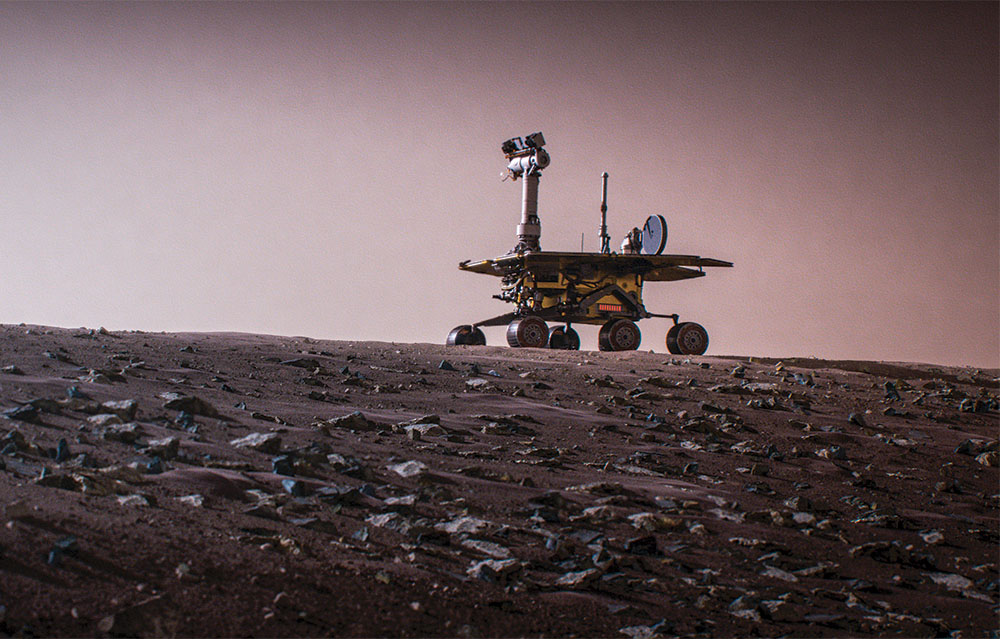

For the feature documentary about NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory’s Exploration Rover Opportunity, Industrial Light & Magic created the extensive Mars sequences in CG, and supervising sound editor/designer Mark Mangini was tasked with creating the sound of the rover. “We wanted to make Oppy somewhat anthropomorphic,” he says. “The engineers themselves set the head of the mast-cam at the height of an average human and the cameras to capture images stereoscopically, like human eyes. However, we didn’t want Oppy to sound whimsical or ‘chatty,’ like many traditional sci-fi robots.” He decided to rely solely on sounds that the rover itself could have made, which involved recording sounds at JPL. “The cheat was in how I organized them,” adds Mangini. “I [incorporated] the sounds of computer disk drives ‘chattering’ and modulated them with my own voice.

“The biggest sound design challenge would be creating the sound of Oppy getting ‘arthritis,’ ” he adds. “As Oppy aged, the many sandstorms took their toll on every moving part, embedding sand into every orifice.” The team “injected sand into Earth-bound mechanical things like bicycle gears and door hinges to approximate the sound of grit and sand scraping across metal surfaces.” He continues, “These sounds were then added to the existing servo motors and mechanicals.”

Mangini says that for the sound of the red planet, “NASA provided the first sound recordings of Mars, sent from Perseverance,” which he incorporated in the doc.

WARNER BROS.

From a sound standpoint, what could be more vital in director Baz Luhrmann’s musical drama than Elvis’ singing? The film first depicts the performer as a young boy in Mississippi, then follows his rise to fame and some of his most classic performances up until his death in 1977. Early tests with Austin Butler, who portrayed the eponymous music icon, led to the realization that the actor would be the filmmaker’s “secret weapon,” allowing the team to blend his vocal performances with those of Elvis Presley. “The first live test was astounding,” recalls Wayne Pashley, supervising sound editor, designer and rerecording mixer. “After a long test day on set, Baz and the whole team knew that Austin had to perform every song live. We would then mix and blend between Elvis himself and the channeled performance of Austin.”

Pashley adds that the sound team used a combination of playback recording and live recording, while restored vintage microphones from each era were used to capture Butler’s performances. “During postproduction, we had Austin come into a controlled ADR record environment, using the same microphones to perform all the breaths, grunts and interstitial vocal tidy-ups,” he says.

In the end, Luhrmann chose to use Butler’s performance in its entirety for songs from the 1950s, then a mix of Elvis Presley’s original recordings with Butler through the 1960s and 1970s (decades in which the quality of the original recordings improved).

NETFLIX

Courtesy of Netflix

One of the goals of supervising sound editor, designer and rerecording mixer Scott Gershin was to give a “sonic signature” to each of the characters — though in animation, everything you hear has to be created to support the drama. For the title character, it began with a lot of wood, including maple, mahogany and rosewood guitar woods, as well as Foley work and library sounds. He notes: “If we only stayed with wood, it only gave us one dimension to the vocabulary of Pinocchio. So then we started adding in little squeaks [and other sounds]. We wanted to find the delicacy of some metal squeaks, a little bit of rubber squeaks and many different types of wood that we used to really define all of the emotions of his movement.”

Gershin cites as an example the point in which Pinocchio is introduced. “At the start, Pinocchio is as much a ‘thing,’ a creature, as anything else. So we wanted to make him feel like he’d just fall apart at any moment. He was creaky and felt very loose-sounding. We wanted to show the fragility of Pinocchio, even later in the [film], when he feels vulnerable. But then there were times where Pinocchio was very stubborn, and he’d cross his [arms]. We had wood lock into place to feel like, ‘I don’t want to do that.’ “

The more aggressive whale-like Dogfish was a combination of sounds of various animals, including elephants, rhinos and cats, paired with Gershin’s own vocalizations to support the story.

MGM/PRIME VIDEO

Vince Valitutti / Metro Goldwyn Mayer Pictures

Ron Howard’s film about the 2018 Tham Luang cave rescue in Thailand was all about immersion. “After early discussions with Ron, we knew we needed to give the water in the caves a very strong identity. Water is the antagonist in the film,” explains supervising sound editor and designer Oliver Tarney. “It is holding the boys captive and hindering access from the rescuers. We sought to give a true sense of how difficult it is to navigate cramped and flooded cave systems and really register how isolated and vulnerable the divers would have felt. Two main parameters we kept focus on were the reduced frequencies of sound underwater, and how difficult it is to discern the source of a sound when you are submerged. … Not instantly knowing where the sound is coming from in that dark, all-encompassing environment serves to heighten the tension, the claustrophobia, and makes for a more interactive experience.”

Supervising sound editor Rachael Tate adds that the team even had a recording session with the real John Volanthen (the British cave diver played by Colin Farrell) in a cave system in the U.K. “We used hydrophones to capture the specific movements of this expert cave diver, his tank clangs, flipper movements, everything we could get,” explains Tate. “His vocalizations were then added to Colin’s diving scenes.”

For scenes outside the cave, elements such as crowds, vehicles and heavy rain all contributed to the experience.

This story first appeared in a December stand-alone issue of The Hollywood Reporter magazine. To receive the magazine, click here to subscribe.