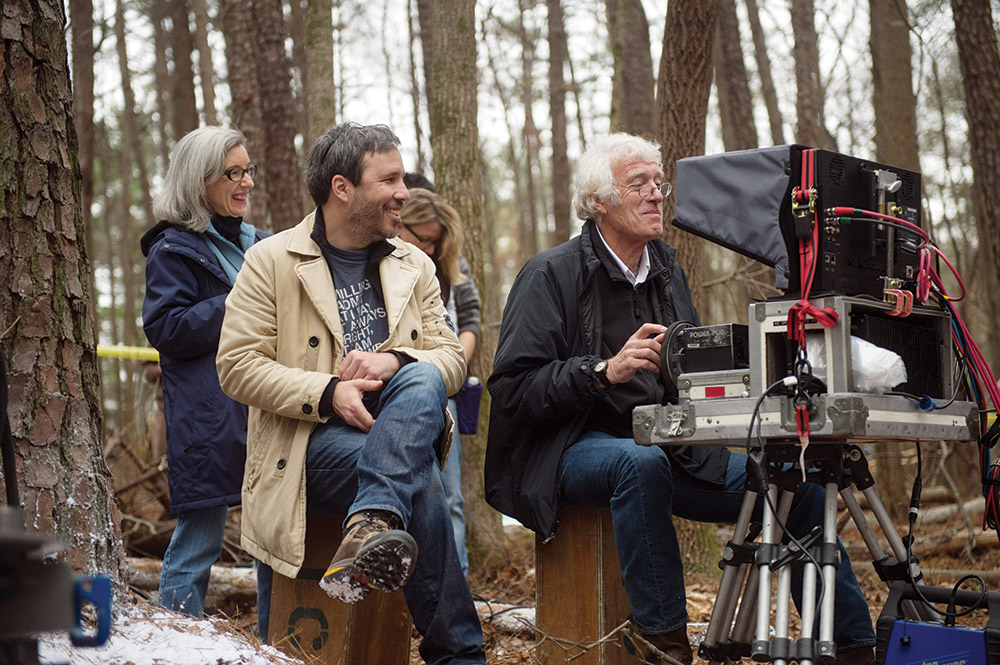

Villeneuve and Roger Deakins on the set of Prisoners, the first of their three collaborations, followed by Sicario and Blade Runner 2049.

Wilson Webb/Warner Bros./Courtesy Everett Collection

You’d be hard-pressed to find a filmmaker who has put together a finer body of work than Denis Villeneuve has since making his U.S. debut in 2013. From the mold-breaking thrillers of Prisoners, Enemy and Sicario to a murderers’ row of sci-fi films including Arrival, Blade Runner 2049 and Dune, the French Canadian director’s films have amassed over $1.1 billion in worldwide box office and landed him three Oscar nominations. His winning streak is all the more impressive when you consider that he put his camera down for much of the 2000s in order to refine his cinematic identity. That nine-year gap was still flanked by a handful of lauded Canadian films, but it wasn’t until 2010’s Oscar-nominated Incendies that Villeneuve felt like he’d finally discovered his signature. Now, Dune: Part Two (March 1) is poised to be his new top grosser after effusive early reactions and reviews.

Renowned cinematographer Roger Deakins, who won his first Oscar for Villeneuve’s Blade Runner 2049, isn’t sure he would’ve been interested in photographing Prisoners, the first of their three collaborations, had he not heard that the director of Incendies was involved. “Like the two great masters of cinema Andrei Tarkovsky and Andrey Zvyagintsev, Denis allows a scene to play out in the time it takes,” Deakins says of the filmmaker. “His work has an all-too-rare honesty.”

Oscar nominee Jake Gyllenhaal met Villeneuve ahead of 2013’s Enemy, the helmer’s last Canadian co-production, and he immediately reteamed with him on the Georgia set of Prisoners, Villeneuve’s American introduction that released first. “One of the very first things Denis said to me when we met about Enemy was that he had to make that film before he could make any other. He falls in love with a story and then he can do nothing else until he’s exorcised that vision,” Gyllenhaal recalls, while also highlighting Villeneuve’s sense of humor and overall demeanor on set. “He is a filmmaker that never lets his ego take the reins.”

With three Villeneuve films under his belt, Oscar nominee Josh Brolin recognized his “standard of excellence” from the moment he stepped onto Sicario’s New Mexico-based set in 2014. “What makes Denis Denis is his lack of pretense,” Brolin shares. “There is always something to learn, and with that learning, he elevates with the next one. So Sicario was a great experience, but Dune was a more profound one.”

While in South Korea during Dune: Part Two’s press tour, Villeneuve, 56, spoke to THR about why he took a career time-out in the aughts, his initial reluctance to work in Hollywood and his desire to step away from the desert of Dune before eventually concluding his trilogy.

Growing up in a small Quebec village, what movies set your filmmaking ambition in motion?

I remember being half-fascinated, half-traumatized by the beginning of 2001: A Space Odyssey. I hid behind the staircase because I wasn’t allowed to watch it on television. Most of the movies I saw as a kid were on TV. I vividly remember seeing a newspaper ad for a particular movie and saying to my parents, “I want to see this.” It was Star Wars. I was absolutely floored by the poetry of it, and it opened a door. I was also struck by Duel and Close Encounters of the Third Kind, so I came to cinema through the lens of Spielberg.

As teenagers, you and your friend designed Dune storyboards. Had you firmly decided your future at that point?

Yeah, we were very arrogant, pretentious teenagers, and that was the ultimate dream. We didn’t have access to cameras then, so I would write stories and my best friend, Nicolas Kadima, would draw them. So the appeal of cinema and science fiction happened at the same time that I discovered Dune. There was something about the journey of a young man who finds a home in another culture, in the deep desert, that absolutely spoke to me.

You went to film school in Montreal, and then gained real-world experience by making short films around the world. Did you learn more abroad than in class?

I had a very strong teacher who taught us the ABCs of filmmaking, but I had the chance to participate in this TV program that sent eight 18- to 25-year-olds around the globe for six months with only a camera. There was no internet, so it was really an adventure. I traveled alone for six or seven months, and each week I had to make a three- to five-minute short film or documentary to be shown on national TV. It was nothing professional, but there was total freedom. So it really shook me to my core, because I’d never been outside of North America. At 22 years old, when I stepped foot in Japan to do a short film, it was by far the best and most important film school.

From 1998 to 2000, you released August 32nd on Earth and Maelström, but then you stayed on the sidelines until 2009’s Polytechnique, based on the Montreal massacre. What prompted the intermission?

When I finished my first two feature films, I realized that I wasn’t happy at all with the results and that the core of the problem was me. I went into filmmaking a bit too quickly, and those movies were driven by ego. It created a movie [August 32nd on Earth] that I wasn’t really proud of. Both movies were well received, but I felt empty at the end of both experiences. So I had to approach cinema differently. I had to learn more about storytelling and, most important, working with actors. So I stopped for many years, saying to myself, “If I go back behind the camera, it’ll be for something meaningful.” For three years, I read and spent time in a theater, watching directors direct plays, to understand how to communicate with actors. I was a sponge. I then started developing what became Polytechnique and Incendies, and it took me many years to write them with other people. So that pause was probably the best and most important artistic decision I’ve ever made. Otherwise, I wouldn’t be here today. I would’ve just repeated myself and died, artistically, quite quickly.

2010’s Incendies, which was nominated for the foreign-language Oscar, is your most celebrated Canadian film, and it established your style and voice. Would you agree?

Absolutely, yes. It honestly touches me to hear you say that, because that’s the film where I got rid of influences and just made something on pure instinct. I’m proud of Polytechnique, but I was still trying things. So Incendies is when I finally found my voice as a filmmaker. I finally felt at home, and it was the payoff of all those years of studying.

In 2013, you made your American debut with the Jake Gyllenhaal-Hugh Jackman two-hander Prisoners, but you were reluctant at first to make the jump to Hollywood. How come?

For foreign directors, Hollywood can be frightening. You hear all those stories of great filmmakers getting crushed by the system and losing their identity. It’s a big machine, and I felt vulnerable. There was something precious and pure about what I had just done with Incendies, and I just wanted to protect that and myself by making future movies with the same kind of artistic integrity. But one of the first [American] screenplays I was sent by my agents at the time strangely felt in direct continuity with Incendies and the thematic cycle of violence. It was Prisoners, so I agreed to meet with the studio and I said to myself, “I’m going to finally meet those infamous Hollywood studio executives.” I then went to L.A. to pitch without fear because I had nothing to lose. I was sure that I wouldn’t get it. And so I just told the truth, and being straightforward might be why I got the project. I wasn’t trying to please them. And to my great surprise, I couldn’t believe how well Prisoners went. I was absolutely respected, and my director’s cut made it to the screen.

Villeneuve and Roger Deakins on the set of Prisoners, the first of their three collaborations, followed by Sicario and Blade Runner 2049.

Wilson Webb/Warner Bros./Courtesy Everett Collection

Your neo-noir film Enemy hit theaters after Prisoners, in early 2014, but you actually shot it first and did post on them both simultaneously. Why did these movies collide?

Enemy was a gift that I gave to myself, honestly. It was made exclusively to experiment with one actor [Jake Gyllenhaal]. It was also a way to see if I would be able to direct in English, and before going into Prisoners, working on an independent movie with a smaller budget felt wise. If I ended up getting crushed by the system on Prisoners, I knew my creative identity would still be intact with Enemy. But both movies were greenlit at the same time, and I had to find a way to make them both without compromising. So I shot Enemy and cut Enemy, and then I went into prep and shot Prisoners. I then did post on both at the same time.

Prisoners (2013) Villeneuve’s first U.S. release, starring Viola Davis and Jake Gyllenhaal, earned frequent collaborator Roger Deakins an Oscar nom. The legendary DP finally won the honor in 2018 for Villeneuve’s Blade Runner 2049.

Warner Bros./Courtesy Everett Collection

You returned with Sicario in 2015, and for all your showstopping scenes with DP Roger Deakins across three movies, what makes Sicario’s final scene in a tiny apartment one of your favorites?

Taylor Sheridan is one of my favorite screenwriters to this day, but that final scene was different in his screenplay, and it was one of the scenes that I changed. I just strongly felt that it should go in another direction. So that final scene was a combination of ideas from me and Benicio Del Toro. And then something happened on the day that deeply moved me, because I felt that I brought the best and most positive creativity out of my actors and teammates. So that beautiful moment in Sicario felt like I was walking in the dark with friends in order to create something meaningful, and I absolutely adored that experience.

You’ve remained in the sci-fi genre ever since your first foray with 2016’s Arrival. Did you put a lot of pressure on yourself at the time, given that you clearly wanted to tell more sci-fi stories?

I always approach each movie like it’s the last one, but I will say that, yes. I was looking for something very specific and very special to enter into the sci-fi genre, and when I read Ted Chiang’s brilliant short story “Story of Your Life,” I knew that was it. There was something about the exploration of language and the perception of reality and the impact of culture on reality that absolutely moved me. So I knew that I had something very special in my hands at the time, and I knew that it would be the perfect project to tackle meaningful science fiction.

Arrival (2016) Amy Adams plays a linguist in the sci-fi feature, which landed Villeneuve his first Oscar nomination.

Jan Thijs/Paramount Pictures /Courtesy Everett Collection

Blade Runner 2049 was the first time you played in somebody else’s cinematic sandbox. Were you ever able to ignore the shadow of Blade Runner?

No, never. Blade Runner is one of my favorite films, and it’s absolutely a masterpiece. Ridley Scott is one of my favorite filmmakers, and even though he had given his blessing, it was very important for me to hear it and see it in his eyes that he was OK with me doing the movie at the time. But I was constantly thinking about the original film as I was making Blade Runner 2049. It was impossible not to. So 2049 was really a love letter to the first film, but it was by far one of the most difficult projects I’ve ever done, and I don’t think I will ever approach someone else’s universe again. I still wake up sometimes at night, saying, “Why did I do that?” I’d declined a few other projects of that scale, but at the time, I said to myself, “It’s a crazy project, but it’s worth the risk of losing everything.”

Blade Runner 2049 (2017) The sequel to Ridley Scott’s seminal 1982 film counts as one of the most challenging of Villeneuve’s career. “I don’t think I will ever approach someone else’s universe again,” he says.

Warner Bros./Courtesy Everett Collection

Your adolescent dream has been realized with Dune: Part One and Part Two. Is your teenage self satisfied?

I have mixed feelings. When I embarked on this adaptation, the first artist I approached was Hans Zimmer, and as much as we were excited by the prospect, I remember him asking me, “Is it a good idea to try to bring our childhood dreams to the screen? Are we meant to fail?” But there have been many moments with the Fremen and Harkonnens [central groups in Dune] that are close to my dream and would have pleased me as a teenager. There are other things that I changed because of the process of adaptation, so it’ll take me years to digest all this. It was the most challenging experience of my life, technically and cinematically, but I still wake up in the morning feeling blessed that I had the chance to make this adaptation.

Dune: Part One (2021) Adapting Frank Herbert’s sci-fi novel was a boyhood dream — and landed the filmmaker two Oscar nominations (for screenwriting and as a producer). The cast includes (from left) Rebecca Ferguson, Zendaya and Javier Bardem.

Chiabella James/Warner Bros.

Frank Herbert’s Dune Messiah picks up 12 years after the events of Dune, which you split in half. Is that partially why you’re in no hurry to finish a trilogy? Do you want the actors to age?

It’s not that. I just finished Part Two very recently, and I went from Part One to Part Two without even an hour in between. I’m not complaining. I feel blessed to work, of course, but it’s just that I physically need to recover for a couple of weeks. It’s also about making sure that I have the right screenplay. I have four projects on the table, currently. One of them is a secret project that I cannot talk about right now, but that needs to see the light of day quite quickly. So it would be a good idea to do something in between projects, before tackling Dune Messiah and Cleopatra. All these projects are still being written, so we’ll see where they go, but I have no control over that.

It sounds like Sicario fans should let go of any delusions regarding you directing Sicario 3.

(Laughs.) It’s funny because I only heard about this project through an interview, but if Taylor Sheridan is the screenwriter, I want to see that movie.

Sicario (2015) Villeneuve rewrote the final scene of the drug cartel drama with help from star Benicio Del Toro (seen here far right, with co-stars Emily Blunt, Josh Brolin and Matthew Page).

Lionsgate/Courtesy Everett Collection

It’s been said that the era of the movie star is over, but Dune: Part Two’s red carpets beg to differ. Do you have all the faith in this next generation?

It’s difficult to talk about this because it’s in motion and we don’t have distance. Maybe we will see the impact in 10 years, but yes, I believe in this new generation. They are very open, very wise, very skilled and very playful. Timothée [Chalamet], Zendaya, Florence [Pugh] and Austin [Butler] play with the red carpet, and it’s stunning how they own that space. [Writer’s note: Anya Taylor-Joy, who has a recently revealed cameo in Part Two, also joined the red carpet fun at the London and New York premieres.] They are very authentic. They are not products. They are artists who own their own identities. They also receive an incredible amount of demand and curiosity from young people. These actors bring out a lot of passion in teenagers and young adults, and I love the fact that they are bringing young people to the theaters. So they are the movie stars of the future, and they will talk to the new generation. This is the future of cinema.

Timothée Chalamet reprises the role of Paul Atreides in Denis Villeneuve’s Dune: Part Two, which opens March 1.

Warner Bros.

You are part of a coalition of filmmakers that purchased the Village Theatre in Westwood. How did that pact come to be?

I came on board through an invitation from Jason Reitman. He is the leader of this community of filmmakers that bought this theater, and I’ve spent years advocating for the in-theater experience. I strongly believe it’ll prevail, and it’s exciting to be on the ground with exhibitors and to be directly in contact with the public in this way. So, as a director, I absolutely love the idea of extending our reach. Film directors are also lonely wolves. Each of us has our own bubble, so it moved me that I was invited to be a part of this group of people I admire. I love the idea that filmmakers can have a voice in the decisions about distribution. So uniting directors together creates a force, and there’s something really powerful about that idea.

You and Christopher Nolan are often compared because you both make thoughtful films on a massive scale. You’ve also moderated Q&As for one another since Arrival, and you invite each other to early screenings of your films. What does his respect mean to you?

It means the world. I also have massive respect for Chris Nolan, and what he’s achieved through the years is very impressive. He’s one of my favorite filmmakers, so to have his respect means a lot.

You and your late friend Jean-Marc Vallée received similar press interest since you both came to the States in 2013. It also seemed like you took turns directing Emily Blunt, Jake Gyllenhaal, Amy Adams and Jared Leto. Did you ever share a laugh about this?

Of course. Jean-Marc was a friend, but that wasn’t calculated. It was really a strange coincidence that there was this dance between us. We were different filmmakers, but we had a similar sensibility regarding our love of actors. I miss him, I must say.

A version of this story first appeared in the Feb. 28 issue of The Hollywood Reporter magazine. Click here to subscribe.