A withering report on sexual abuse and cover-up in the Southern Baptist Convention, the largest Protestant denomination in the U.S.

A viral video in which a woman confronts her pastor at an independent Christian church for sexually preying on her when she was a teen.

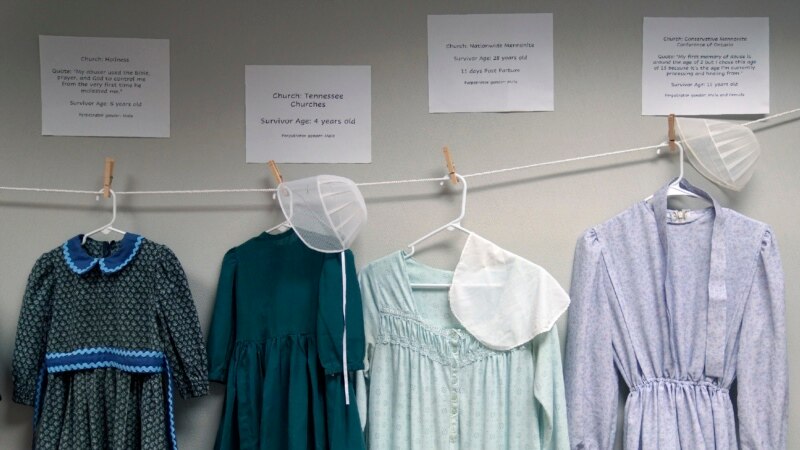

A TV documentary exposing sex abuse of children in Amish and Mennonite communities.

You might call it #ChurchToo 2.0.

Survivors of sexual assault in church settings and their advocates have been calling on churches for years to admit the extent of abuse in their midst and to implement reforms. In 2017 that movement acquired the hashtag #ChurchToo, derived from the wider #MeToo movement, which called out sexual predators in many sectors of society.

In recent weeks #ChurchToo has seen an especially intense set of revelations across denominations and ministries, reaching vast audiences in headlines and on screen with a message that activists have long struggled to get across.

“For us it’s just confirmation of what we’ve been saying all these years,” said Jimmy Hinton, an advocate for abuse survivors and a Church of Christ minister in Somerset, Pennsylvania. “There is an absolute epidemic of abuse in the church, in religious spaces.”

Calls for reform will be prominent this week in Anaheim, California, when the Southern Baptist Convention holds its annual meeting following an outside report that concluded its leaders mishandled abuse cases and stonewalled victims.

The May 22 report came out the same day an independent church in Indiana was facing its own reckoning.

Moments after its pastor, John B. Lowe II, confessed to years of “adultery,” longtime member Bobi Gephart took the microphone to tell the rest of the story: She was just 16 when it started, she said.

The video of the confrontation has drawn nearly 1 million views on Facebook. Lowe subsequently resigned from New Life Christian Church & World Outreach in Warsaw.

In an interview, Gephart said she’s not surprised that so many cases are now coming out. She has received words of encouragement from all over the world, with people sharing their own “heartbreaking” stories of abuse.

“Things are shaking loose,” Gephart said. “I really feel like God is trying to make things right.”

For many churches, she said, “It’s all about covering up, ‘Let’s keep the show going.’ There are hurting people, and that’s not right. I still don’t think a lot of the church gets it.”

Hinton — who turned in his own father, a former minister now imprisoned for aggravated indecent assault — said the viral video demonstrates the potency of survivors telling their own stories.

“Survivors have far more power than they ever think imaginable,” he said on his “Speaking Out on Sex Abuse” podcast.

#ChurchToo revelations have emerged in all kinds of church groups, including liberal denominations that preach gender equality and depict clergy sexual misconduct as an abuse of power. The Episcopal Church aired stories from survivors at its 2018 General Convention, and an archbishop in the Anglican Church of Canada resigned in April amid allegations of sexual misconduct.

But many recent reckonings are occurring in conservative Protestant settings where a “purity culture” has been prominent in recent decades — emphasizing male authority and female modesty and discouraging dating in favor of traditional courtship leading to marriage.

On May 25 reality TV personality Josh Duggar was sentenced in Arkansas to more than 12 years in prison for receiving child pornography. Duggar was a former lobbyist for a conservative Christian organization and appeared on TLC’s since-canceled “19 Kids and Counting,” featuring a homeschooling family that stressed chastity and traditional courtship. Prosecutors said Duggar had a “deep-seated, pervasive and violent sexual interest in children.”

On May 26 the Springfield (Missouri) News-Leader reported on a spate of sex abuse cases involving workers at Kanakuk Kamps, a large evangelical camp ministry.

Emily Joy Allison, whose abuse story launched the #ChurchToo movement, said the sexual ethic preached in many conservative churches — and the shame and silence it breeds — are part of the problem. She argues that in her book, “#ChurchToo: How Purity Culture Upholds Abuse and How to Find Healing.”

Allison told The Associated Press that addressing abuse requires both a change in church policy and theology. But she knows the latter is unlikely in the SBC.

“They need to undergo a transformation so radical they would be unrecognizable at the end. And that will not happen,” Allison said. Reform work focused on “harm reduction” is a more realistic approach, she said.

Some advocates hope the front-burner focus on abuse could lead to lasting reforms — if not in churches, then in the law.

Misty Griffin, an advocate for fellow survivors of sexual assault in Amish communities, recently launched a petition drive seeking a congressional “Child’s Rights Act.” As of early June, it had drawn more than 5,000 signatures.

It would require that all teachers, including those in religious schools and homeschool settings, be trained about child abuse and neglect and subject to reporting mandates, and would also require age-appropriate instruction on abuse prevention for students. Griffin said such legislation is crucial because in authoritarian religious systems, victims often don’t know help is available or how to get it.

“Without that, nothing’s going to change,” said Griffin, a consulting producer on the documentary “Sins of the Amish.”

The two-episode documentary, which premiered on Peacock TV in May, examines endemic abuse in Amish and Mennonite communities, saying it is enabled by a patriarchal authority structure, an emphasis on forgiving offenders and reluctance to report wrongdoing to law enforcement.

The Southern Baptist Convention, whose doctrine also calls for male leadership in churches and families, has been particularly shaken by the #ChurchToo movement after years of complaints that leadership has failed to care for survivors and hold their abusers accountable.

At its annual meeting, the SBC will consider proposals to create a task force that would oversee a listing of clergy credibly accused of abuse. But survivors criticized that proposal and are calling for a more powerful and independent commission to perform that task and also review allegations of abuse and cover-up. They’re also seeking a “survivor restoration fund” and memorial dedicated to survivors.

Momentum for change grew as survivors such as Jules Woodson, who went public in 2018 with a sexual assault accusation against her former youth pastor, were emboldened to tell their stories.

“I felt like, ‘Thank God there’s a space where we can tell these stories,’” Woodson said.

Such accounts led to the independent investigation, whose 288-page report detailed how the SBC’s Executive Committee prioritized protecting the institution over victims’ well-being and preventing abuse.

The committee has apologized and made public a long-secret list of ministers accused of abuse.

Woodson said seeing her abuser’s name on it felt like a double-edged sword.

“It was in some ways validating that my abuser was on there, but it was also devastating to see that they knew and yet nobody in the SBC spoke up to warn others,” she said.

Woodson added that she is still waiting for meaningful change: “They have offered minimal words acknowledging the problem, but they have offered zero reform and true action which would show genuine repentance or care and concern for survivors or the vulnerable people who have yet to be abused.”