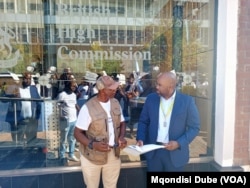

Scores of people from communities living near wildlife in Botswana marched Tuesday against an anti-hunting bill presented to Britain’s House of Commons. The protesters delivered a petition to the British High Commission as Botswana prepares to send a delegation to the U.K. to lobby against the bill.

The Hunting Trophies (Import Prohibition) Bill, which goes for a second reading later this month, seeks to ban the importation of legally obtained wildlife trophies from Africa.

Trophy hunting is the practice of killing large animals such as elephants, lions and tigers for sport. Hunters often keep the heads or other parts of the animals for display.

One of the organizers of the march, Poniso Shamukuni, said if the measure passes, it will negatively impact livelihoods of communities living side-by-side with wildlife in Botswana. The African nation, for example, has the world’s largest elephant population at more than 130,000, and the giant animals are often in conflict with humans.

“We implore your government to carefully consider the implications of enacting the Hunting Trophies (Import Prohibition) bill. Such a decision could have far-reaching negative consequences on wildlife populations, exacerbate human-wildlife conflicts, undermine conservation efforts, and impact the livelihoods and well-being of communities residing in wildlife areas,” said Shamukuni.

Shamukuni said Botswana’s wildlife numbers are stable and reintroducing the hunting ban could lead to a rise in poaching, as previously witnessed.

Botswana, under former president Ian Khama, placed a moratorium on hunting in 2014. The ban was lifted by his successor, Mokgweetsi Masisi, in 2019.

European nations are now pushing for a ban on trophy hunting, arguing it poses a threat to wildlife populations.

Last September, in the U.K., the House of Lords blocked the anti-hunting bill after it had moved easily through the House of Commons.

Amy Dickman, a professor of wildlife conservation at the University of Oxford, said lobbying groups pushing for the hunting ban have misled the British parliament.

“They have suggested these bans will help reduce wildlife extinctions. For example, they say the bans will undermine the livelihood of communities. All these things can be and should be rebutted with robust evidence that exists. It is a complicated topic; it’s science specific. But actually, trophy hunting is not driving extinction of any species you can find and that it does contribute, importantly, to local revenues and the funding of major threats such as anti-poaching and habitat loss,” said Dickman.

During Botswana’s hunting season, which runs from April to September, mostly international hunters pay up to $50,000 to hunt species like elephants.

They are only allowed to hunt aging males so as not to affect the breeding of species.

Local conservationist Map Ives calls for an approach other than hunting.

“I am of the opinion that we should start to look at wildlife and of course, the natural ecosystem as something that supports all life on Earth, including that of humans. I often feel the phrase it pays, it stays, is a kind of a form of eco-blackmail. In other words, if it does not support humans, then it can die,” said Ives.

Currently, Botswana issues about 300 elephant hunting licenses per year.

Botswana communities earned $3 million from last year’s hunting season, which, among other things, is used for conservation programs.