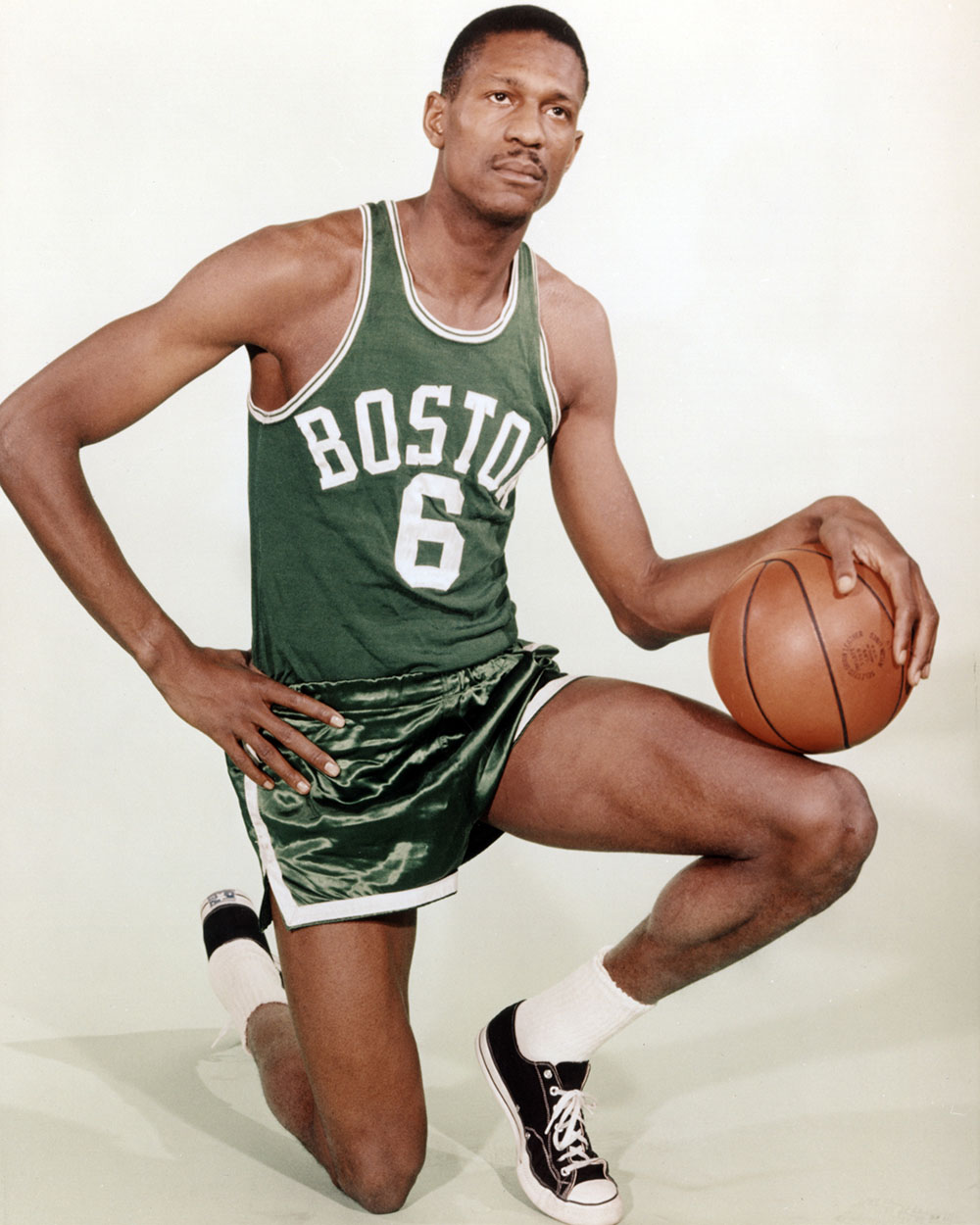

Courtesy Everett Collection

Bill Russell, the intimidating center who rejected layups and bigotry with equal authority while leading the Boston Celtics to pro basketball’s greatest dynasty, died Sunday, his family announced. He was 88.

Russell won five Most Valuable Player awards and the Celtics captured 11 NBA championships during his 13-year career, including eight in a row from 1959-66. His powerful adversary during the 1960s, Wilt Chamberlain, ended the streak by leading the Philadelphia 76ers to the league title.

The 7-foot-1 Chamberlain and the 6-foot-9 Russell met 142 times in an epic rivalry of big men that riveted basketball fans for a decade. His Celtics went 57-37 against Chamberlain’s teams during the regular season and owned a 29-20 advantage in the playoffs.

“Wilt and Russell were to basketball what Arnold Palmer was to golf,” 76ers Hall of Fame forward Billy Cunningham once said. “Turn on the television on Sunday, and there they were. They are the two greatest talents to ever play the game.”

While establishing himself as pro basketball’s ultimate winner, Russell was a powerful advocate for civil rights. At the ESPYs in 2019, he received the Arthur Ashe Courage Award, given annually to those who “stand up for their beliefs, no matter what the cost.”

Russell’s experiences growing up impoverished in Oakland, California, shaped his intolerance of racism. Even as an established NBA star, he still found himself grappling against bigotry on an everyday basis. When the Celtics were on the road, their Black players routinely were denied the same housing and restaurant meals offered to the rest of the team.

After leading the Celtics to their initial championship as a rookie in 1956-57, Russell moved his family to Reading, Massachusetts, 16 miles north of Boston. A few years later, vandals broke into his home, destroying his trophies and defecating in his bed.

When the Celtics retired Russell’s No. 6 before a home game against the New York Knicks in 1972, he insisted on a brief, private ceremony to be staged an hour before fans were allowed in the building. In his 1979 memoir, Second Wind, he labeled Boston “a flea market of racism.”

“Bill is a proud man who has been offended by a racist society, and he won’t give an inch to it,” former Celtics teammate Bob Cousy once said. “So it is obvious that Russ always had a very strong chip on his shoulder, and he demonstrated that to the outside world at every opportunity. His public persona was to thumb his nose at whitey.”

The thoughtful Russell participated in the March on Washington in 1963 and invested in a program to purchase rubber plantations in Liberia to create jobs in African nations. And in 1967, he participated alongside Jim Brown, Lew Alcindor (now Kareem Abdul-Jabbar) and other athletes in a news conference to support Muhammad Ali’s refusal to be drafted into the service.

“Bill Russell didn’t wait until he was safe to stand up for what was right,” said late Georgetown coach John Thompson, another onetime Celtics teammate. “He represented things that were right while he had something to lose.”

Despite his fame, Russell refused to sign autographs and often seemed aloof to Boston fans. Instead of courting public acclaim, he focused on defense, rebounding — he once had 51 rebounds in a game — and winning championships under legendary coach Red Auerbach.

After Auerbach retired in 1966, Russell became the first Black coach in North American professional sports. As player-coach, he guided Boston to NBA titles in 1968 and 1969 before announcing his retirement.

Courtesy Everett Collection

In Russell’s farewell as a player, the Celtics edged Chamberlain’s Los Angeles Lakers 108-106 in Game 7 of the NBA Finals on May 4, 1969. The final minutes of that game caused a long-standing rift between Russell and Chamberlain.

The two were fierce combatants who enjoyed mutual respect through the years until Russell questioned Chamberlain for taking himself out in the late stages of Game 7 because of an injured knee.

The two didn’t speak to each other for 20 years before Russell apologized to Chamberlain in person. When Chamberlain died in October 1999 at age 63, a grieving Russell spoke at the service.

“Wilt and I were not rivals,” he said. “We were competitors. In a rivalry, there’s a victor and a vanquished. He was never vanquished.”

While Chamberlain set scoring records, Russell was content to maximize the skills of his teammates. “It wasn’t a matter of Wilt versus Russell with Bill,” said former Celtics star John Havlicek. “He would let Wilt score 50, if we won. The thing that was most important to him was championships.”

When told that Chamberlain had just signed a contract for $100,000, a prideful Russell went immediately to Auerbach’s office and demanded one dollar more.

William Felton Russell was born on Feb. 12, 1934, in Monroe, Louisiana. His late older brother, Charlie L. Russell, was a playwright whose most famous work, Five on the Black Hand Side, premiered in 1969 and was adapted into a 1973 film starring Godfrey Cambridge.

Russell’s mother, Katie, died when he was 12, and he struggled early on the basketball court, failing to make his junior high school squad. He was almost cut from the team at McClymonds High School in Oakland but persevered and steadily developed his skills as an adept shot-blocker.

Coming out of high school, Russell received just one letter of interest, from the University of San Francisco. However, playing with future Celtics teammate K.C. Jones, he would lead the Dons to consecutive NCAA championships in 1955 and 1956, averaging 20.7 points and 20.3 rebounds a game in his three seasons.

He also competed in collegiate track before the crafty Auerbach engineered a draft-day trade with the St. Louis Hawks to bring Russell to Boston.

Before his NBA rookie season, Russell served as captain of the 1956 U.S. Olympic men’s basketball team that won a gold medal at the Melbourne Games. By promptly leading the Celtics to the 1957 title, he won championships at the NCAA, Olympic and pro levels, all within a 13-month span.

He finished his career as the No. 2 rebounder in NBA history behind Chamberlain, excelling as Boston’s last line on defense and triggering a devastating fast break that wore down opponents.

Although Russell played with future Hall of Famers like Cousy, Havlicek, Sam Jones, K.C. Jones, Bill Sharman and Tommy Heinsohn, it was his leadership and indomitable will to win that keyed the Boston dynasty.

“I always looked at it like we were going against the best team in the world,” Chamberlain once said. “Going to the Boston Garden was like going to the amphitheaters of the Romans — where the Christians were thrown to the lions. They were so good, and he was so good.”

Before big games, Russell would routinely throw up in the locker room. After a while, Celtics teammates urged him to vomit as a sign he was ready to dominate. At times, he would wear a black suit and a cape to the arena.

“I thought he was Count Dracula, so we started calling him Count Russell,” said Sam Jones. “I asked him why did he wear a black suit and he says, ‘Well, I’m like a mortician. I come to bury the players I’m playing against.’ That’s Bill Russell … very, very different.”

Russell, a longtime resident of Mercer Island in Washington state, also coached the Seattle SuperSonics for four seasons beginning in 1973. In 1987, he returned to the NBA bench, signing a seven-year deal to coach the Sacramento Kings. Russell was fired after a 17-41 start, finishing his coaching career with a 341-290 record.

Courtesy Everett Collection

Away from the court, Russell acted on several TV shows, playing a ranch hand on ABC’s Cowboy in Africa in 1967, a butler on ABC’s It Takes a Thief in 1968, a teacher on NBC’s The Bill Cosby Show in 1971 and a judge on NBC’s Miami Vice in 1986. He also appeared with Gary Coleman and Maureen Stapleton in the 1981 film On the Right Track.

Meanwhile, he showed up as himself on Rowan and Martin’s Laugh-In in 1971-72, hosted Saturday Night Live in 1979 and served as an NBA analyst for ABC, CBS and TNT, displaying his trademark high-pitch laugh.

In addition to Second Wind, he wrote three other books: 1966’s Go Up for Glory, 2001’s Russell Rules and 2009’s Red and Me.

Dorothy Anstett, Miss USA in 1968, was one of Russell’s four wives. He and his first wife, college sweetheart Rose, had a daughter, Karen, and two sons, William Jr. and Jacob. Survivors also include his fourth wife, Jeannine.

The statement announcing his death concluded with: “Bill’s wife, Jeannine, and his many friends and family thank you for keeping Bill in your prayers. Perhaps you’ll relive one or two of the golden moments he gave us, or recall his trademark laugh as he delighted in explaining the real story behind how those moments unfolded. And we hope each of us can find a new way to act or speak up with Bill’s uncompromising, dignified and always constructive commitment to principle. That would be one last, and lasting, win for our beloved #6.”

In 2011, President Obama presented Russell with the Medal of Freedom, saying, “Bill Russell stood up for the rights and dignity of all men. He marched with Martin Luther King and he stood by Muhammad Ali. When a restaurant refused to serve the Black Celtics, he refused to play in the scheduled game.”

Inducted into the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame in 1975, Russell was honored with a bronze statue outside Boston City Hall in 2013 and received the NBA Lifetime Achievement Award in 2017.

His impact on modern-day players, on and off the court, remains profound.

“What he’s done for civil rights in this country is unmatched,” said Charles Barkley. “Him and Ali will always be my heroes as far as that goes. Those guys did all the heavy lifting back in the day.”

From the moment he became a professional, Russell never wavered in his love for the Celtics. He respected Auerbach for the dignity in which he treated all Boston players, regardless of skin color.

“The Celtics were a way of life for me, a group of people so diverse you cannot imagine,” Russell said. “Working together day in and day out for a common goal. I thoroughly enjoyed my teammates. I always said when I left the Celtics, I could not go to heaven because that would be a step down.”