Source: Nielsen streaming rankings, August 2020-April 2022; THR research

Bigger, better, fewer. That is the refrain inside Netflix that feature film executives, led by division chief Scott Stuber, are grappling to operate under as the digital streaming giant changes course and confronts new realities, such as lagging subscriber growth (it lost 200,000 subs in its latest quarter) and rising competition (Disney’s bundle of Disney+, Hulu and ESPN+ now has 205 million subs combined, just behind Netflix’s 221 million global subs).

The Hollywood Reporter spoke to multiple sources, ranging from executives to producers to agents with ties to the company, to paint a picture of a streaming giant that is trying to get its mojo back after a shocking earnings disclosure April 19 (Netflix has lost 44 percent of its stock value since that day). “Morale is stuck at stock level,” says one executive semi-jokingly. Another executive describes the mood within Netflix right now as “distracted” given the changes.

It’s easy to see why. The company, in response to Wall Street, has taken cost-cutting measures such as axing more than 150 employees, or 2 percent of its workforce. TV and other parts of the company have taken their hits, but a pointed focus is the features division. A good portion of cuts have wiped out the kids and family film division, and the original independent features division, which made movies in the under-$30 million budget range, has also seen its ranks cleaned out.

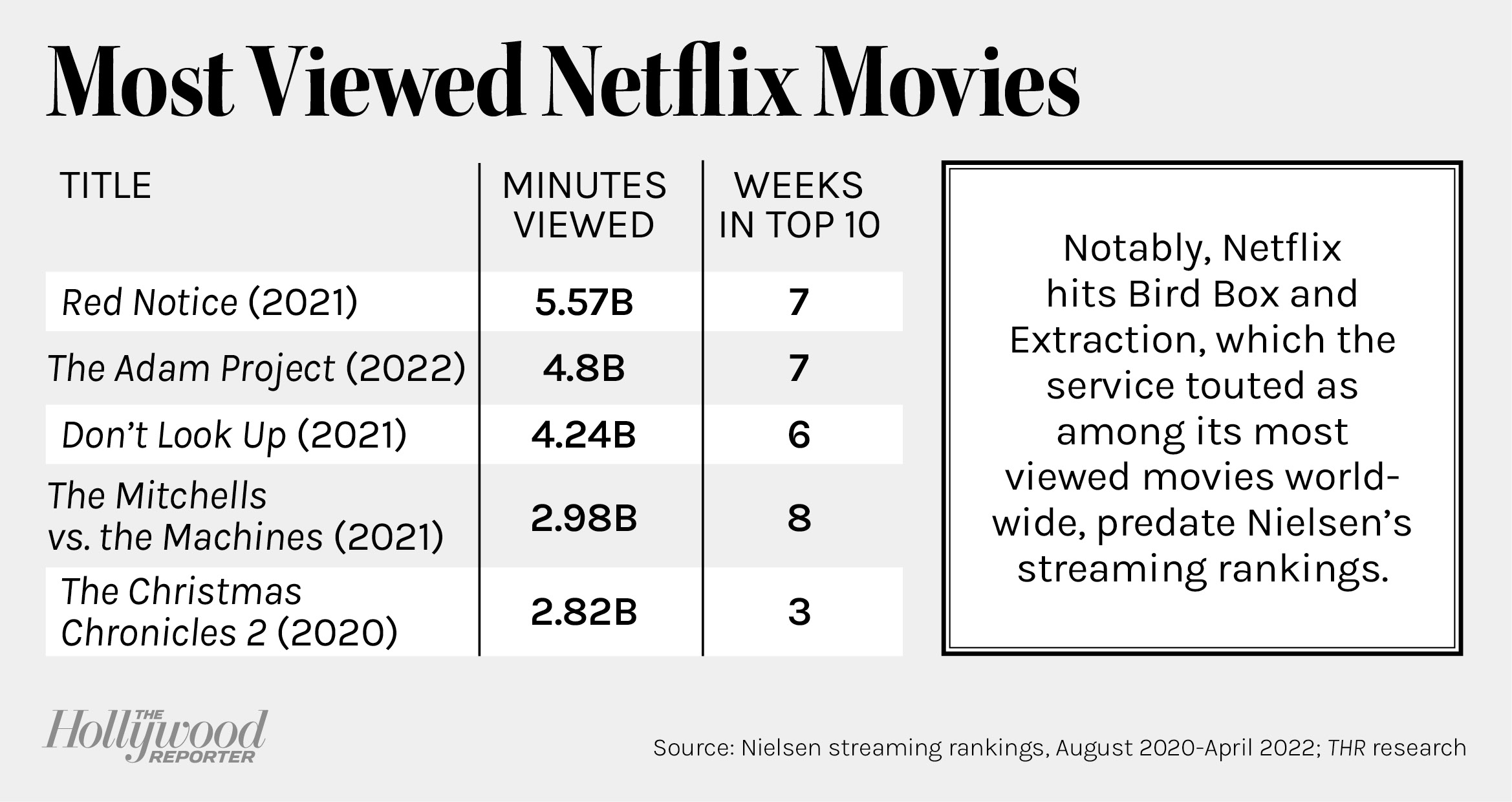

As it moves forward, Netflix wants to focus on making bigger movies, making better movies, and releasing fewer than it previously did at a gluttonous pace. “Just a few years ago, we were struggling to out-monetize the market on little art films,” Netflix co-chief Ted Sarandos told analysts on the company’s April earnings call. “Today, we’re releasing some of the most popular and most watched movies in the world. Just over the last few months, things like Don’t Look Up and Red Notice and Adam Project, as examples of that.” But what this “bigger, better, fewer” directive means is unclear to those inside and outside the company.

“Small movies are not going to go away,” says one insider, but they could become more niche and cater to a passionate audience. Another insider concurs, saying the output will be reduced, lessening the need for so many execs. “They were overstaffed with executives,” says this insider. Also, bigger doesn’t necessarily mean more $150 million movies. Expect to a see a more subtle change — instead of making two movies for $10 million, as an example, the company will make one for $20 million. “The goal will be to make the best version of something instead of cheapening out for the sake of quantity,” says one insider. And the streamer remains in the acquisitions game, as evidenced by the recent $50 million-plus deal for the Emily Blunt thriller Pain Hustlers.

On Netflix’s earnings call, Sarandos pointed to “big event films” like The Gray Man and Knives Out 2 as a way of driving sub growth. Gray Man, starring Ryan Gosling and Chris Evans in a $200 million-plus budgeted film directed by Avengers: Endgame duo Anthony and Joe Russo, will hit select theaters July 15 before bowing on the service July 22. Meanwhile, Knives Out 2 — the next chapter of the whodunit franchise from director Rian Johnson and star Daniel Craig, for which Netflix hammered out a $469 million deal in March 2021 — is set to bow in the fourth quarter of this year. “The upcoming slate in ’22, we’re confident, is better and more impactful than it was in ’21,” Sarandos noted to analysts on the April call.

Animation is also under scrutiny, with a disciplined ax taken to projects that were on the bubble and the frequency of releases also being diminished, although a “new movie every week” is still the goal, be it live action or animation.

The moves are a far cry from only a few years ago, when movies that cost over $100 million or $150 million were rare. That was also the time when Netflix was frequently cited in the media as the savior of the mid-budget movie, and of such once-theatrical staples as romantic comedies and thrillers. Always Be My Maybe, The Kissing Booth and To All the Boys I’ve Loved Before became hits, made social media stars out of their actors and even launched mini-franchises.

The company isn’t giving much specific direction right now, either. “Conversations will be happening with producers and directors in the coming weeks about size and genres,” says one producer who has a meeting on the books and is eagerly awaiting insight. But this is an uncertain moment for the streaming giant, which could see still more cuts and possible executive exits, leaving some producers and agents leery. “Am I comfortable bringing them a package right now? No, I’m not,” says one partner. (Netflix co-chief Reed Hastings didn’t exactly give film chief Stuber or TV leader Bela Bajaria a boost of confidence when Maureen Dowd, in a New York Times profile published May 28, asked about the likelihood of top executives staying put and he replied: “Um, the way we are organized, no one gets to make that assumption.”)

One thing many agree on is that the era of expensive vanity projects at Netflix, whether animation or live action (like Martin Scorsese’s $175 million The Irishman), is likely over. “This tendency to do anything to attract talent and giving them carte blanche is going away,” says one person. As always, there will be exceptions — this is Hollywood, after all — but in essence, this new era seems to be marked by one idea: discipline.

Source: Nielsen streaming rankings, August 2020-April 2022; THR research

This story first appeared in the June 1 issue of The Hollywood Reporter magazine. Click here to subscribe.