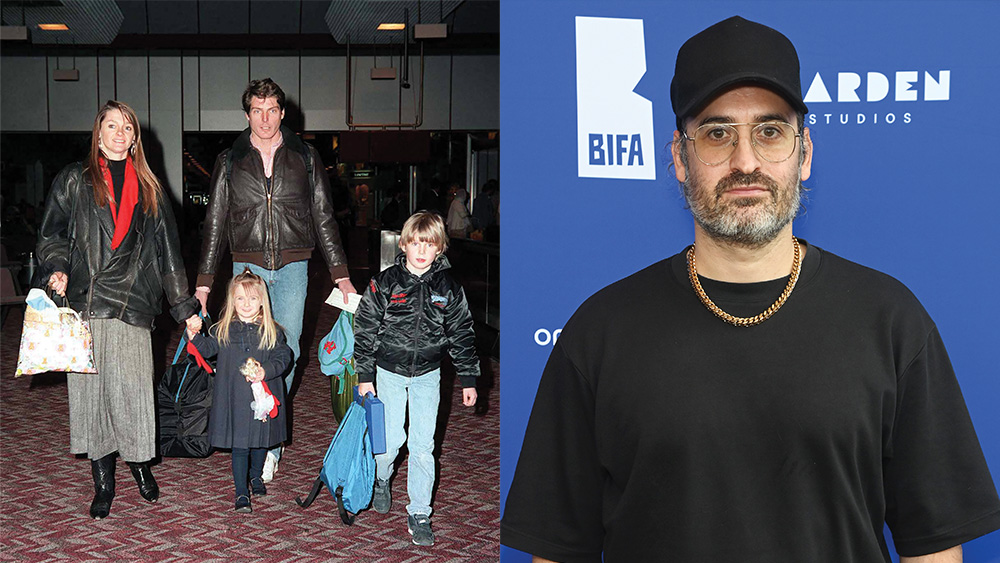

From left: Super/Man: The Christopher Reeve Story and Ian Bonhote

Mirrorpix/Courtesy of Warner Bros. Pictures; Alan Chapman/Dave Benett/Getty Images

Six directors of standout 2024 documentaries gathered in late November for THR’s annual Documentary Roundtable.

Two were veteran American documentary filmmakers: R.J. Cutler, who helmed Netflix’s Martha, a portrait of Martha Stewart that explores the price of pursuing perfection, and Disney’s Elton John: Never Too Late, which contrasts the rise to stardom with the farewell tour of the singer-songwriter (David Furnish co-directed the latter); and Matt Tyrnauer, director of Greenwich Films’ Carville: Winning Is Everything, Stupid, a profile of James Carville, the legendary Democratic strategist. Another was Swiss-born Ian Bonhôte, whose third doc, which he directed with Peter Ettedgui, is Warner Bros.’ Super/Man: The Christopher Reeve Story, in which the life, work and tragic accident of the titular beloved movie star is examined 20 years after his death.

The other three were there on behalf of their first feature-length docs: Carla Gutiérrez, a veteran film editor, who helmed Amazon/MGM’s Frida, an unconventional look at the short, rocky but remarkable life of Mexican artist Frida Kahlo; Emily Kassie, who directed Nat Geo’s Sugarcane, an excavation of the long-buried history of wrongdoing at an Indian residential school in Canada (she co-directed with Julian Brave NoiseCat); and Natalie Rae, who made Netflix’s Daughters, which highlights a program that helps incarcerated men and their daughters reconnect at a dance (she co-directed with Angela Patton).

The sextet discussed their paths to nonfiction, what they feel they owe a subject in return for the subject’s participation, how they think Donald Trump’s re-election will impact the documentary community and more.

Before we talk about your 2024 films, how did you come to nonfiction filmmaking in the first place?

R.J. CUTLER I started my career as a theater director but always knew that I would end up in nonfiction. I had Don’t Look Back calling to me, Harlan County, USA, the Rolling Stones film Gimme Shelter. In 1992, I had this idea that somebody ought to be chronicling the Clinton campaign. The War Room [the resulting doc, on which Cutler served as a producer] was an extraordinary experience, most of all because I was learning at the feet of the masters D.A. Pennebaker and Chris Hegedus.

EMILY KASSIE I made my first documentary when I was 14, and it was used as a PSA in Canada. In college, I made a documentary that won a Student Academy Award. And from there, I went into newsrooms as a visual journalist, making documentaries, creating immersive multimedia pieces and doing photojournalism about conflicts all over the world. I became particularly interested in people caught in the crossfire of geopolitical conflict and surviving atrocity. That’s been the theme of my career.

MATT TYRNAUER I was a writer for Vanity Fair. At that time, we wrote 10,000-word articles. I eventually realized that these pieces were like documentaries. I was very influenced by the Maysles’ kind of observational filmmaking, where you don’t insert yourself in the story, but your presence is looming around the edges, and I’d model some of my pieces after that format. I thought, “Documentary filmmaking could be a progression if I could figure out how to finance a film.” I was looking for a big character and found one in Valentino Garavani, the great fashion designer. I realized his story had never been told, so I told it in Valentino: The Last Emperor.

CARLA GUTIÉRREZ In my last semester of college, I took a class on experimental video, and there was a film that I watched called Fear and Learning in Hoover Elementary, about a law in California that was being discussed that would require teachers to report their undocumented students. I grew up in Peru, so I didn’t have a lot of access to films. That film showed me the power of the form. I applied to film school and went to the Stanford documentary program with the intention of being a filmmaker. But I fell in love with editing, and I’ve been doing that for over 20 years.

IAN BONHÔTE I was a child actor …

KASSIE Me too! But I don’t tell anyone.

BONHÔTE Really?

KASSIE Yeah. It was a really joyful part of my childhood.

BONHÔTE I was an overactive child raised by a single mom, and I needed to channel my energy somewhere, so I started at 7. By 17, I’d done many plays and started to act onscreen — but I’m from Switzerland, so my fame was minuscule. I fell in love with filmmaking when I lived in Venezuela for a while. I was involved with music and the queer community back in Switzerland, and that led to music videos and, when I was 23, to starting a company that grew into a major player in documentaries and fiction. I later met up with Peter Ettedgui, my creative partner, and we directed a documentary about Alexander McQueen. That was our first.

NATALIE RAE When I was 6, I came home one day from school really disturbed about this concept I’d learned about, endangered species, and was like, “Dad, why isn’t everyone talking about this?” He was like, “If you want to do something about it, you could make something called a documentary.” And he helped me make my first documentary. In my 20s, I got passionate about PSAs. If I could make someone cry in 30 or 60 seconds, and millions could see that within a few days, that was powerful. That became a tool that I got addicted to for years.

Let’s discuss the origins of your 2024 projects.

RAE My best friend sent me a TED Talk by Angela Patton. She was like, “This woman’s saying the same things you are: ‘Wisdom lives inside of young women’ and ‘the rest of the world can stand back and learn from them.’ ” I watched it, loved it, reached out to Angela and met her for coffee. She was like, “Get in line, girl. There are 500 directors emailing me.” But she now says that I was the first to see it from the girls’ perspective, to know that this was a story about the leadership of young Black women, and not about recidivism and the prison system. So we decided to work together.

BONHÔTE On our second film, Rising Phoenix, which is about the paralympic movement, we explored the world of disability. That led an archive producer of ours to message Matt Reeve [one of Christopher’s sons] out of the blue on LinkedIn. The family had received loads of interest in making a documentary over the years and always said no. But, with the 20th anniversary of Chris’ death coming up, they felt ready.

From left: Super/Man: The Christopher Reeve Story and Ian Bonhote

Mirrorpix/Courtesy of Warner Bros. Pictures; Alan Chapman/Dave Benett/Getty Images

KASSIE In 2021, there was a New York Times story about the discovery of unmarked graves on the grounds of an Indian residential school in Canada. These were schools that, for over 150 years, in both Canada and the U.S., had forcibly separated Indigenous children from their families and put them into assimilationist schools, many of which were run by the Catholic Church. I’d spent a decade telling stories about atrocities all over the world, but I’d never looked at the country I grew up in. I felt in my gut that this was a story that I had to pursue. I texted my friend Julian Brave NoiseCat. We’d worked our first reporting jobs together a decade earlier, and in the years since, he’d become one of the greatest writers on Indigenous life in North America, so I hoped to collaborate. He said, “Let me give it some thought.”

That same day, I went looking for a nation that was going to do a search — it felt natural to tell a narrative arc that started with a search. I found an article about the Williams Lake First Nation in British Columbia, and sent a cold email to the chief, Willie Sellars. He called me back and said, “The Creator has always had great timing. Just yesterday, our council said, ‘We need someone to document this search.’ ” So I got on a Zoom with the council, got my gear together, booked a flight to Williams Lake and two weeks later was ready to go. That’s when Julian called me back and said, “Hey, I’m open to working with you.” I said, “That’s great, Jules. I’m going to be following this search at a school called St. Joseph’s Mission near Williams Lake.” He went silent and then said, “That’s crazy. Did you know that that’s the school that my family attended? And I heard a rumor that after my father was born, he was put in a dumpster nearby.” It felt fated that we should make this together.

GUTIÉRREZ I discovered Frida Kahlo when I was 19. I used to procrastinate in college by walking to the art section of our library and opening books. One day, I opened a book of Latin American art and saw one of her paintings, of her standing between the U.S. and Mexico, representing the conflicted feelings that she had for the U.S. I was a young immigrant, and it also reflected my feelings of being in this new place that wasn’t always welcoming.

Decades later, I had a miscarriage. I was surprised that women don’t talk to each other about such things. I think one of the reasons why Frida has become such a symbol of female empowerment is because she did. I was grateful to a painting of hers where, after a miscarriage, she shows her body in a raw way. Her story’s been told many times, but usually we hear historians talking about her. I wanted the audience to have the experience of swimming in the pool of her emotions and have that connection that I had when I first saw that painting of hers. That was the beginning.

TYRNAUER I remember seeing The War Room. I loved it. Then, one of the first assignments I had at Vanity Fair was covering the ’92 Clinton campaign, so I encountered Carville. Thirty years on, a mutual friend of Carville’s and mine called and said, “What do you think about a documentary on Carville? Do you know someone who’d want to direct that?” I thought, “Well, yeah.” The War Room was at the beginning of Carville’s fame. He’d been a serial flop in his profession until his mid-40s, then became a household name in part because of the film. But that was a generation ago. The first part of his post-Clinton-victory fame was this peculiar marital fame [Carville is married to Republican strategist Mary Matalin]; that’s faded from memory, but it was huge, and that was interesting to me. Then, the 2024 election cycle turned out like none other, and Carville inserted himself into the process while I was shooting. He began to assail Biden for being too old to run for president; no one else in the party was saying this. That took over the arc of the film.

Winning is Everything, Stupid and Matt Tyrnauer

Courtesy of CNN Films; Emma McIntyre/Getty Images

CUTLER I was planning to have dinner with a friend who called to say, “Martha Stewart would like to join us.” I’d never met Martha and didn’t know a lot about her, but I said, “Sounds lovely.” At dinner, I was seated next to her, learned about her and realized, “This is a story of 20th and early 21st century American womanhood, of survival and of a visionary.” And she was ready to tell her story, so we moved forward. And when it was difficult for her to talk, she showed us letters to her husband or diaries from prison or vérité footage from the weeks between her conviction and sentencing.

A few months later, I’m invited to lunch with [Elton John’s husband] David Furnish. David said, “I’m thinking about making a film about the final months of Elton’s touring career. Elton has decided to leave the road after 60 years because he wants to spend the rest of his life focused on his family. What do you think?” I said, “Sounds beautiful and moving.” I’d always thought that there was a great movie to be made about the first five years of Elton’s career, when he stepped into the void created by The Beatles breaking up, by Hendrix’s and Joplin’s deaths, and by rock ’n’ roll not knowing where it was going. He was bigger than you can imagine. Thirteen albums in five years, seven of which went to No. 1. When you think about Elton’s catalog, pretty much all those songs were written during that period — when he was also utterly unfulfilled as a person. My pitch was, “Let’s have the final months be the spine, and the first five years be the nervous system, and then they’ll all come together.”

From left: Elton John: Never Too Late, Martha and R.J. Cutler

Sam Emerson/Disney; Courtesy of Netflix; tephanie Augello/Variety/Getty Images

Cameras can alter people’s behavior. What did you do on these projects to mitigate that?

KASSIE There’s a very problematic history of documentary in the lives of indigenous people. Arguably the first “documentary” was Nanook of the North, about Inuit in northern Canada, and it was a patronizing and unreal depiction. The director, Robert Flaherty, wanted to convey a particular message about who these people were and their ability to govern themselves. He also fathered a bunch of kids up there and then ran away. This was a legacy that it was essential for us to reject in the way that we approached this film. We decided to make a film in a vérité style that didn’t sit them down and try to extract things from them, but rather to live alongside them and gain their trust over time; we shot 160 days over two and a half years. And we made an artistic choice to shoot on prime lenses because we wanted to have to physically earn the intimacy — we couldn’t zoom in to those moments, but rather had to move our bodies. And to be that close, you had to gain trust.

CUTLER One of the phrases that does this process the least service is “fly on the wall,” because we’re not flies on a wall; we’re human beings in a room, and as human beings in a room, we’re in a relationship, and as people in a relationship, we have to establish trust with the other people in the relationship. The way you establish trust is by being trustworthy. There’s no other way.

RAE Our film centers on a five-hour event where a kind of miracle takes place in front of your eyes. One girl’s idea turned into a letter that opened the heart of a sheriff who said yes, he would let a bunch of young girls come through security and dance with their fathers in a jail. The weight of capturing this dance — this sort of urban legend that had happened only a few times — was great.

We wanted to shoot it on 16-millimeter: two cameras, medium lenses, being really careful about our space and intimacy with the families and knowing we’d miss moments while reloading. Now that I see the impact that the film’s making, I think that having that dance shot on celluloid, having those moments of texture and light captured in that way, makes it what it is. When the girls walk down that hallway and it’s a bit overexposed and out of focus, and they’re coming in and the fathers are waiting, after the whole film the girls had been waiting? This moment of the girls now having that agency to come toward their fathers was so powerful. Cambio [Fernandez], my cinematographer, was crying so hard that he was like, “My iris is full of tears. I have no idea if anything will be in focus, but I pray to God it is.” We got the footage back, and it was in focus.

Daughters and Natalie Rae

Courtesy of Netflix; Mat Hayward/Getty Images

Some of your subjects weren’t around to see your films. For those whose subjects were, at what point did you allow them to see what you’d been doing? And how much do you care about the way they feel about what you’ve done?

TYRNAUER Carville didn’t ask to see any cuts. He saw the movie at its premiere at Telluride. That’s unusual. Usually people get curious and ask — sometimes in the form of a contract — to see cuts, which for me, as a journalist, is problematic. Carville, when he saw it, was convulsively sobbing. He really liked the film. But at Vanity Fair, I wrote stories about people, and very frequently the people hated the story. In fact, I wrote a couple about Martha Stewart — she loved one, and boy, did she hate the other.

CUTLER But she’s very subtle when she doesn’t enjoy something! [Editor’s note: That’s a joking reference to Stewart publicly criticizing aspects of Cutler’s documentary.]

TYRNAUER I’m not out to get people, but if the subject doesn’t like what I do, I feel it’s almost irrelevant.

CUTLER I have great respect for Matt, but I have a completely different approach. My feeling is that the story belongs to the subject, not me. They’ve trusted me to tell their story, and before it’s done, close to the end, I believe I have a duty to share it with them and hear what they think. I went to Wyoming and showed Dick Cheney The World According to Dick Cheney with [his wife] Lynne and [daughter] Liz in the room, and God knows what firearms were in the house, but afterward we had one of the most fascinating conversations. After about an hour he said, “We trusted R.J. to make his film. I would’ve made a different film. This is the film he made. Let’s talk about something else.”

I get that journalists operate differently, and I respect that. But I’m not approaching this as a journalist. I’m approaching it as a filmmaker. With Martha, she’s had all sorts of different responses. Even her criticisms have supported the film because they draw attention to it. But she’s also recently made a number of TV appearances where she’s like, “You know what? It wasn’t as bad as I thought.” You must approach this with empathy and understand that it’s hard to be the subject of one of these films; you’re going to have an extremely subjective response to how you look. But recently she called and was like, “I want the names of everyone who worked on the film. I’m going to send them a book.” Elton? He was like, “I’m so fat!” (Laughs.) That was the first time he saw it. Then he came to the first screening in Toronto and had a similar reaction to Carville’s — moved to the point where we had to wait 10 minutes to do the Q&A.

KASSIE With Sugarcane, there was an unbelievable sense of responsibility because we’re correcting the record, and that comes with the stories of hundreds of people who suffered unbelievable abuse and a community that’s been extracted from and systematically oppressed. What’s my responsibility to those people, as a non-Indigenous filmmaker, and having Julian as my creative partner who’s in the film? We needed to show the community, particularly our participants and the council, before it went to Sundance. It was absolutely imperative that they know what we had made. Luckily, they felt heard and seen by it.

GUTIÉRREZ It’s not the easiest thing to work with a figure that’s passed away, either. There’s a whole universe of people who are incredibly invested in Frida. We heard from a few, making sure that we didn’t call her a “feminist,” because that word didn’t exist when Frida was alive.

From left: Frida and Carla Gutierrez

Courtesy of Amazon MGM Studios; Monica Schipper/Getty Images

BONHÔTE Working on a documentary about someone who’s passed away, you interview people who shared the life of the subject, so it’s their life too, in a way, that you’re being entrusted with.

Do you think that Donald Trump’s re-election will have an effect on the documentary world?

KASSIE I hope not. But now is a time when artists, journalists and storytellers are more important than ever. So to the streamers and other places that might have the power to make sure they’re heard, have courage.

GUTIÉRREZ I’m really afraid as to what’s going to happen with CPB [the Corporation for Public Broadcasting] and PBS and the closing of doors that have been outlets for filmmakers that don’t necessarily follow the mandates of the market.

TYRNAUER The battle lines will be drawn in the documentary world. We live in a world dominated by social media that’s shortform, yet there’s a tremendous lust for longform storytelling — podcasts go on for three hours and people binge limited series for seven hours. If newspapers, a dwindling cohort, are cooperating in advance, who’s going to have the platform and ability to tell longform, sophisticated stories and, one hopes, get them out to an audience? Documentary filmmakers.

CUTLER We’ve always had to be industrious. The first thing D.A. Pennebaker said to me was, “If you want to learn about documentary filmmaking, you’d better understand that you need a bank robber’s mentality: Travel light and always be ready to make a run for it.”

From left: Sugarcane and Emily Kassie

Emily Kassie/Sugarcane Film LLC; Courtesy of James K. Lowe

Finally, please recommend one great 2024 documentary not represented at this table …

KASSIE Black Box Diaries. I was blown away by Shiori Ito’s courage.

GUTIÉRREZ No Other Land. It’s a necessary watch.

CUTLER I love Black Box Diaries as well.

BONHÔTE Witches, which explores menopause. As a middle-aged man, it taught me a lot.

RAE Hollywoodgate stands out. To be able to build the trust of the Taliban and film with them for the greater part of a year is so commendable.

TYRNAUER I’m going with Black Box Diaries and Hollywoodgate. Those were extraordinary.

KASSIE Because of the copycats, I’m going to say a different one: Union. It’s an important window into labor rights, and Amazon has made it very difficult to see.

This story first appeared in a December stand-alone issue of The Hollywood Reporter magazine. To receive the magazine, click here to subscribe.