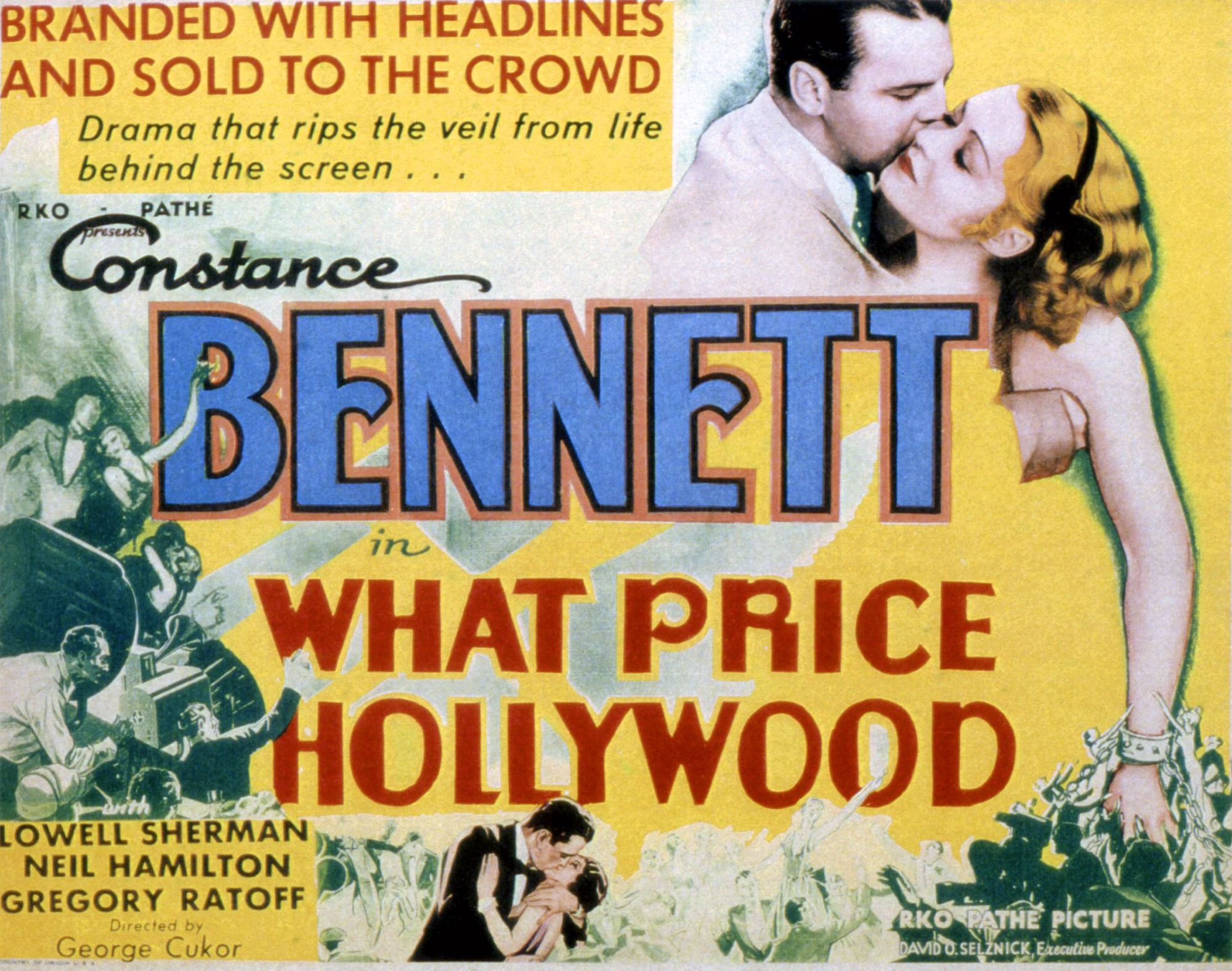

The theatrical poster for 1932’s What Price Hollywood?

Everett

In Apple TV+’s The Studio, Seth Rogen plays Matt Remick, a studio boss just appointed to run the apparently fictional Continental Pictures. Fueled by hyperkinetic camerawork and dialogue that name-checks the celebrities who are not actually dragooned into making cameos, the series promises an under-the-hood look at the sputtering engine of the motion picture industry in the age of streaming. Judging by the first episodes, Matt is not, in the oft-quoted phrase of F. Scott Fitzgerald, among the select handful of man who have been able “to keep the whole equation of pictures in their heads.” In fact, he has trouble with the basic arithmetic.

Hollywood cinema has ever been a medium of self-reflexivity, mining its own art and business for story material, so the latest depiction of above-the-line talent — oddly, there is a paucity of films about gaffers, best boys, or foley artists — is part of a venerable tradition.

How venerable? In 1896, Thomas Edison, the original American motion picture producer, in all senses of the word, collaborated with the illustrator J. Stuart Blackton for a brief vignette entitled Blackton, the Evening World Cartoonist. The film shows Blackton sketching a portrait of Edison as filmed by the Edison Manufacturing Company.

Edison aside, the studio boss has mainly been a tangential character in the self-caressing film á clef genre (also known as “inside-Hollywood” or “Hollywood on Hollywood” films). It reserves most of the close ups for stars being born (or flaming out) and directors who serve as surrogates for the last name in the opening credits. Screenwriters, who were treated by the front office as the disposable help, got a measure of revenge by portraying their employers as idiots or vulgarians whose sole role in filmmaking was to write the checks and gum up the works. The producer in Sullivan’s Travels (1941) wants the idealistic director to keep churning out variations on Ants in Your Pants of 1938, the producer in Sunset Blvd. (1950) recalls turning down Gone With the Wind (1939) because the public didn’t like Civil War pictures, and the producer in Singin’ in the Rain (1952) thinks The Jazz Singer (1927) is a passing fad.

The first portals into the world behind the studio gates were fan magazines and gossip columns, but the movies themselves soon offered a crash course into the means of production. In 1915, Universal Pictures founder Carl Laemmle opened Universal City to tour groups and followed up with the two-reel comedy A Day at Universal City (1915). Billed as “a surprisingly funny sketch of life in a motion picture studio,” it showed producer-director Al Christie supervising the scenario department, filming, editing, lab work, and screenings.

By the 1920s, moviegoers had already become well-schooled in how the sausage got made on the factory floor. In King Vidor’s Show People (1928), the delightful Marion Davies sends up Hollywood — and her own persona — with the assurance that audiences understood the no-longer-inside jokes, spotted the cameos, and laughed at how the feckless leading man takes credit for the exploits of his stunt double. Of course, Davies had a studio boss in her pocket, media mogul and Cosmopolitan Pictures producer William Randolph Hearst, for whom she was much more than a side chick. The best cameo in the film is Davies’s own: when the character spots Marion Davies on the lot, she crunches up her face as if to say, “she’s not so hot.”

The studio boss is the featured player in a forgotten obscurity by director Mark Sandrich, The Talk of Hollywood (1929), an early talkie shot with the camera bolted to the floor. Nat Carr, a comedian who was a mainstay of Hebrew-Hibernian shtick in films such as Koster Kitty Kelly (1926) and Private Izzy Murphy (1926), plays the shtetl-bred J. Pierpoint Ginsberg, a silent film producer who must make the transition into the talkies. Problems does he have? Don’t ask. “I asked you for a chorus of sixty,” he kvetches to his casting director. “I didn’t mean that’s how old they should be!”

The theatrical poster for 1932’s What Price Hollywood?

Everett

The ethnic stereotype was dialed back in George Cukor’s What Price Hollywood? (1932), produced by David O. Selznick, who should know. The backstage, rather soundstage, melodrama was not so much an exposé of the town under the real estate sign but a review session of lessons already learned. Star Constance Bennett plays a starstruck waitress at the Brown Derby who moons over Gable and imitates Garbo before finding herself on the cover of the fan mags she lives by. Her narrative arc from bit player to name in lights coincides with a deep dive into Hollywood’s star making machinery: ad-pub boys, gossip columnists, proto-paparazzi, and gala premieres. Russian-born Gregory Ratoff plays Bennett’s kind-hearted, Yiddish-accented studio chief, a type who, said Variety at the time, “is closer to some film producers in his portrayal than the average audience will realize.”

In 1941, two novels by two Hollywood screenwriters placed the producer front and center in the Hollywood story: the unfinished, posthumously published The Last Tycoon by F. Scott Fitzgerald and What Makes Sammy Run by Budd Schulberg. As the son of B. P. Schulberg, the longtime head of production at Paramount Pictures, Schulberg boasted impeccable inside dopester credentials. The anti-hero of his book is Sammy Glick, a venal go-getter who leapfrogs from copy boy to agent to producer by stealing credit and backstabbing friends. “Such things ARE in Hollywood and Budd reports them with fine detachment,” wrote Fitzgerald, generously praising the competition in a letter to Bennett Cerf, Schulberg’s editor at Random House.

Everyone in Hollywood figured Glick was based on the outsized personality and (allegedly) unscrupulous behavior of screenwriter turned producer Jerry Wald. Not that Wald was the only candidate whose mercenary modus operandi fit the character. At The Hollywood Reporter, Irving Hoffman pointed out that “it is not entirely fair to identify Sammy with Jerry to the exclusion of at least half a dozen other possibilities.” Schulberg always said Sammy was a composite, which didn’t stop producers he had never met from glaring at him in restaurants.

The hero — not antihero — of The Last Tycoon is Monroe Stahr, a thinly disguised stand-in for MGM’s Irving Thalberg, the “boy genius” who was running Universal Studios at age 20, when he was still too young to sign the company’s payroll checks. Hired away by Louis B. Mayer for MGM, he became the presiding genius of “the genius of the system,” the name the French gave to the assembly-line quality control maintained by the Hollywood studios. In 1936, when he died suddenly at the age of 36, the industry-wide shock was seismic. “Hollywood in Gloom,” headlined the Reporter. “Death of Thalberg Sinks Industry; All Mourn Passing of Great Producer.”

The front page of The Hollywood Reporter‘s Sept. 15, 1936 issue.

It was Thalberg who inspired Fitzgerald’s “whole equation” panegyric and planted the seed for The Last Tycoon. In 1939, writing to an editor at Collier’s, Fitzgerald confided that Stahr “is Irving Thalberg — and this is my great secret.” The secret seems to have been well kept for neither the trade reviews nor Edmund Wilson in his introduction to The Last Tycoon mentions the obvious model. Tellingly, at the time, no Hollywood studio green lighted either What Makes Sammy Run? or The Last Tycoon for feature film treatment. It was left to the emergent rival medium to adapt both books in 1949 for live performances on NBC’s Philco Television Playhouse.

The threat from television was probably behind the surge of Hollywood-minded films in the postwar era, as if the motion picture industry wanted to remind the public that the real glamour and art was still up on the big screen in films such as Sunset Blvd., Singin’ in the Rain, The Star (1952), A Star Is Born (1954), and The Big Knife (1955) “Producers used to think that a film with a Hollywood background meant a kiss of death,” wrote gossip columnist Hedda Hopper, noting the vibe shift. Traditionally too, the old guard had been wary of airing its dirty linen at the corner Bijou. After a screening of Sunset Blvd, on the Paramount lot, MGM chief Louis B. Mayer confronted Billy Wilder. “You bastard,” he shouted. “You should be tarred and feathered and run out of Hollywood!”

Actually, it was Mayer who was run out of Hollywood in 1951, ousted for younger blood, his right-hand man Dore Schary, the personification of a new generation of more urbane and erudite studio bosses. Under Schary, MGM released what may be the best of the producer-centered dissections of Hollywood life, The Bad and the Beautiful (1952), a whiplash smart corporate melodrama directed by Vincente Minnelli and written by Charles Schnee and George Bradshaw. Told in flashback, the film traces the progress of producer Jonathan Shields (Kirk Douglas) from B-movie dreck to A-list Oscar winners to box office flops. Desperate for a fresh start, he calls together three former collaborators, all of whom he has mentored and betrayed: a director (Barry Sullivan), a star (Lana Turner), and a screenwriter (Dick Powell). “Some of the best movies are made by people working together who hate each other’s guts,” he figures. Douglas — never better than when he was playing a heel (see also Champion [1949] and Ace in the Hole [1951]) — has a terrific time as the conniving, charismatic SOB with the scruples of Sammy Glick and the talent of Irving Thalberg. After a preview screening, Lana Turner sent Douglas a telegram he must have treasured: “I Wasn’t Bad and You Were Beautiful.”

Naturally, “the town is buzzing over the identity of the producer in Metro’s The Bad and the Beautiful,” whispered gossip columnist Sheila Graham, who didn’t name her suspect. I always figured Shields was based on Twentieth Century-Fox’s ruthless and brilliant Darryl F. Zanuck, but the actual producer of the film — John Houseman — revealed in his memoir Front and Center, published in 1979, that “there is no question that substantial elements of David O. Selznick’s personality are to be found in our hero-villain Jonathan Shields.” He also said Selznick hired a lawyer look at the film to see if there was anything actionable. There wasn’t.

The theatrical poster for 1952’s The Bad and the Beautiful.

Everett

In tune with the times, the 1960s nurtured a raw and cynical perspective on Hollywood that made Sunset Blvd. look like a valentine. Richard Rouse’s hate letter The Oscar (1966), which was nominated for none, stars Stephen Boyd as a Sammy Glick-ish actor who uses and abuses cast, crew, agent, and girlfriends. New York Times critic Bosley Crowther panned it as “another distressing example of Hollywood befouling its own nest,” but producer Rouse defended his cutthroat take on the business, claiming that at screenings in Los Angeles “the Hollywood people in the audience gave an almost audible gasp at the truth of what they were seeing.” Maybe not coincidentally, the nicest guy in the vipers’ nest is the producer played by Joseph Cotton. No wonder the actresses in Valley of the Dolls (1967) zone out on drugs.

In the 1970s, the most memorable portrait of a producer is the mogul played by John Marley in The Godfather (1972) who wakes up next to horse’s head by way of incentive to reconsider a casting decision. However, the decade also witnessed, finally, a screen version of The Last Tycoon, produced by Sam Spiegel (who also fit the title), directed by Elia Kazan, written by Harold Pinter, and starring a sleek Robert De Niro as Stahr.

Drunken screenwriters, actors struggling with erectile dysfunction, earthquakes on the backlot — it’s all in a day’s work for Stahr. Watching a slate of dailies, he makes snap decisions on which take to print and which scene to delete. Before getting sunk by a turgid love story — the kind of cinematic dead zone Thalberg would have blue-penciled in the screenplay stage — The Last Tycoon provides a good sense of what a producer actually does. In THR, Ron Pennington described Stahr as “an Irving Thalberg-type producer who never took screen credit but who was truly an artist in that he had the ability to create by effectively combining the various talents of other artists,” which is as good a definition of the producer-as-auteur as Fitzgerald’s “the whole equation.” (Film critic Kenneth Turan nicked the phrase for his splendid dual biography, Louis B. Mayer and Irving Thalberg: The Whole Equation, published earlier this year.)

As the last century came to a close, studio bosses and aspiring studio bosses alike were often portrayed as ready to kill for a bankable film project. In writer-producer Michael Tolkin and Robert Altman’s The Player (1992), studio executive Griffin Mill (Tim Robbins) takes time out from the joys of ordering “off the menu” at four-star restaurants to murder a screenwriter to secure a desirable property. In Get Shorty (1995), all the gangsters want to make a lateral career move into film production by packaging a sure-fire project. The winner of the Hollywood sweepstakes is film buff and loan shark muscle Chili Palmer (John Travolta), who knows the difference between Rio Bravo (1959) and El Dorado (1966).

2002’s The Kid Stays in the Picture

Everett

If any film can bring the studio boss cycle full circle, it is Nanette Burstein and Brett Morgan’s bio-doc The Kid Stays in the Picture (2002). Based on Robert Evans’ 1994 memoir and narrated by the man himself, the film tells of the last, so far, of the old school, hands-on Hollywood producers, who oversaw the second golden age of Paramount Pictures from 1967 and 1974. The first act includes a Hollywood original story so unlikely that no screenwriter would dare pitch it to a producer. While sunbathing at the Beverly Hills Hotel, the actress Norma Shearer noticed an attractive young man at poolside talking on a telephone. His intense energy reminded her of her late husband — Irving Thalberg. She insisted Evans be cast as Thalberg in the Lon Chaney biopic Man of a Thousand Faces (1957). Not a star but a producer was born.