Europeans scrolling their phones and computers are getting new choices for default browsers and search engines, where to download iPhone apps and how their personal online data is used.

They’re part of changes required under the Digital Markets Act, a set of European Union regulations that six tech companies classed as “gatekeepers” — Amazon, Apple, Google parent Alphabet, Meta, Microsoft and TikTok owner ByteDance — will have to start following by midnight Wednesday.

The DMA is the latest in a series of regulations that Europe has passed as a global leader in reining in the dominance of large tech companies. Tech giants have responded — sometimes reluctantly — by changing some of their long-held ways of doing business, such as Apple allowing people to install smartphone apps outside of its App Store.

The new rules have broad but vague goals of making digital markets “fairer” and “more contestable.” They are kicking in as efforts around the world to crack down on the tech industry are picking up pace.

Here’s a look at how the Digital Markets Act will work:

Which companies must follow the rules?

Some 22 services, from operating systems to messenger apps and social media platforms, will be in the DMA’s crosshairs.

They include Google services such as Maps, YouTube, the Chrome browser and Android operating system, plus Amazon’s Marketplace and Apple’s Safari Browser and iOS.

Meta’s Facebook, Instagram and WhatsApp are included as well as Microsoft’s Windows and LinkedIn.

The companies face the threat of hefty fines worth up to 20% of their annual global revenue for repeated violations — which could amount to billions of dollars — or even a breakup of their businesses for “systematic infringements.”

What effect will the rules have globally?

The Digital Markets Act is a fresh milestone for the 27-nation European Union in its longstanding role as a worldwide trendsetter in clamping down on the tech industry.

The bloc has previously hit Google with whopping fines in antitrust cases, rolled out tough rules to clean up social media and is bringing in world-first artificial intelligence regulations.

Now, places such as Japan, Britain, Mexico, South Korea, Australia, Brazil and India are drawing up their own versions of DMA-like rules aimed at preventing tech companies from dominating digital markets.

“We’re seeing copycats around the world already,” said Bill Echikson, senior fellow at the Center for European Policy Analysis, a Washington-based think tank. The DMA “will become the de facto standard” for digital regulation in the democratic world, he said.

Officials will be looking to Brussels for guidance, said Zach Meyers, assistant director at the Center for European Reform, a think tank in London.

“If it works, many Western countries will probably try to follow the DMA to avoid fragmentation and the risk of taking a different approach that fails,” he said.

How will downloading apps change?

In one of the biggest changes, Apple has said it will let European iPhone users download apps outside its App Store, which comes installed on its mobile devices.

The company has long resisted such a move, with a big chunk of its revenue coming from the 30% fee it charges for payments — such as for Disney+ subscriptions — made through iOS apps. Apple has warned that “sideloading” apps will come with added security risks.

Now, Apple is cutting the fees it collects from app developers in Europe that opt to stay within the company’s payment-processing system. But it’s adding a 50-euro cent fee for each iOS app installed through third-party app stores, which critics say will deter the many existing free apps — whose developers currently don’t pay any fee — from jumping ship.

“Why would they possibly opt into a world where they have to pay a 50 cent per-user fee?” said Avery Gardiner, Spotify’s global director of competition policy. “So those alternative app stores will never get traction, because they’ll be missing this huge chunk of apps that would need to be there in order for customers to find the store attractive.”

“That is utterly at odds with the very purpose of the DMA,” Gardiner said.

Brussels will be closely scrutinizing whether tech companies are complying.

EU competition chief Margrethe Vestager said this week that after 10 years on the job, “I have seen quite a number of antitrust cases and quite a lot of creativity built into how to work around the rules that we have.”

How will people get more options online?

Consumers won’t be forced into default choices for key services.

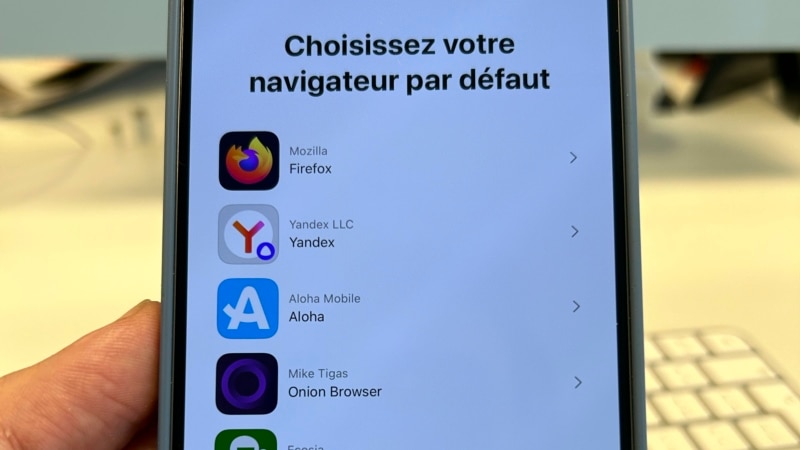

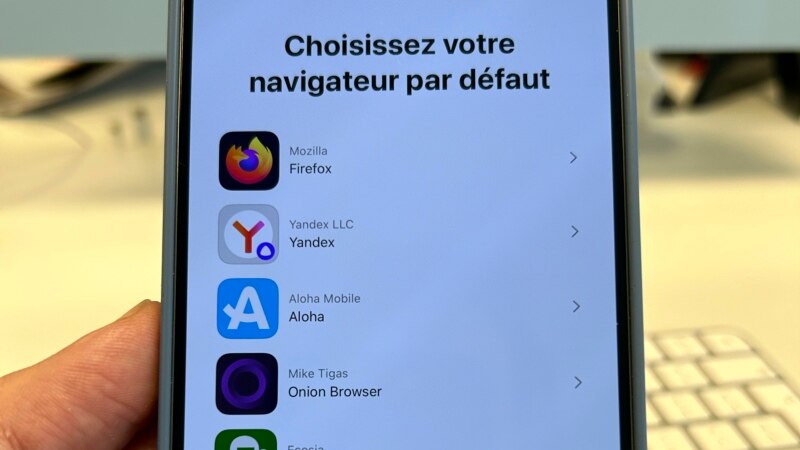

Android users can pick which search engine to use by default, while iPhone users will get to choose which browser will be their go-to. Europeans will see choice screens on their devices. Microsoft, meanwhile, will stop forcing people to use its Edge browser.

The idea is to stop people from being nudged into using Apple’s Safari browser or Google’s Search app. But smaller players still worry that they might end up worse off than before.

Users might just stick with what they recognize because they don’t know anything about the other options, said Christian Kroll, CEO of Berlin-based search engine Ecosia.

Ecosia has been pushing for Apple and Google to include more information about rival services in the choice screens.

“If people don’t know what the alternatives are, it’s rather unlikely that many of them will select an alternative,” Kroll said. “I’m a big fan of the DMA. I am not sure yet if it will have the results that we’re hoping for.”

How will internet searches change?

Some Google search results will show up differently, because the DMA bans companies from giving preference to their own services.

So, for example, searches for hotels will now display an extra “carousel” of booking sites such as Expedia. Meanwhile, the Google Flights button on the search result display will be removed and the site will be listed among the blue links on search result pages.

Users also will have options to stop being profiled for targeted advertising based on their online activity.

Google users are getting the choice to stop data from being shared across the company’s services to help better target them with ads.

Meta is allowing users to separate their Facebook and Instagram accounts so their personal information can’t be combined for ad targeting.

The DMA also requires messaging systems to be able to work with each other. Meta, which owns the only two chat apps that fall under the rules, is expected to come up with a proposal on how Facebook Messenger and WhatsApp users can exchange text messages, videos and images.