Ten US states control and profit from federal Indian reservation lands

It is commonly assumed that the U.S. government holds in trust all land inside Indian reservation borders for the exclusive use of tribes.

This week, High Country News and the nonprofit online news magazine Grist report that 10 state governments hold trust to 647,500 hectares (1.6 million acres) of surface and subsurface acres of lands inside 83 federal Indian reservations.

Tribes have little to no say over how the lands are used, and state-run mining, grazing, logging and leasing generate millions of dollars that are used to support non-Indigenous agencies such as public schools, prisons or universities.

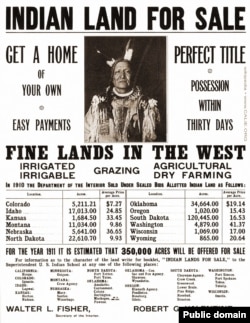

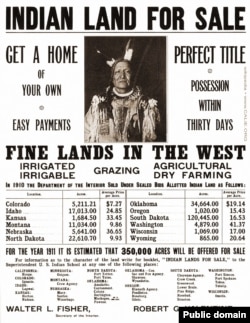

In 1887, Congress passed the General Allotment Act, or Dawes Act, carving up reservations into smaller parcels that were doled out to families and individuals. The remaining land — about 36,400,000 hectares (90 million acres) — was sold or opened up to U.S. states, settlers and federal projects such as state parks.

States are legally obliged to make money from state trust lands, so there is no incentive for them to turn land back over to tribes “without something in exchange.” Some tribes, such as the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes in Montana, have negotiated land back. Others have purchased land back a parcel at a time.

Read more:

ProPublica focuses on museums that got a head start on NAGPRA compliance

As part of its ongoing series examining institutions’ failure to comply with the 1990 Native American Grave Protection and Repatriation Act, or NAGPRA, ProPublica reports this week on two museums that have met most or all their obligations under NAGPRA, which forbids federally funded institutions from retaining human remains and artifacts without permission from tribes.

They are the Museum of Us in San Diego, California, and the History Colorado Center in Denver, both of which got an earlier start than other institutions in cataloging their holdings and consulting with tribes on how remains and funerary artifacts should be managed and repatriated.

In 2018, three decades after NAGPRA was passed, the Museum of Us — then known as the San Diego Museum of Man — released new “Colonial Pathways” guidelines, acknowledging that it had “long prevented the return of cultural resources to Indigenous communities.”

At the time, the museum estimated that at least 80% of its 75,000 “ethnographic items” would require consultation with descendant tribal communities. The museum admitted that it had “long prevented the return of cultural resources to Indigenous communities.”

That process is ongoing, but in Denver, the History Colorado Center has already repatriated all items subject to NAGPRA. It also loans items back out to tribes on request and allows tribes to change their minds and reclaim items.

Read more:

Editorial: Repatriation does not erase Native Americans’ cultures

In an opinion piece this week, Native News Online editor Levi Rickert writes that while museums are making moves to comply with NAGPRA, he believes some “conservative columnists, politicians and benefactors” are pushing back against revised regulations that require them to obtain tribal or lineal descendants’ consent before exhibiting or conducting research on human remains and related cultural items.

“Since 1492, non-Natives have continually sought to research, examine and showcase our continent’s Indigenous peoples,” Rickert writes. “This fascination led to museums collecting hundreds of thousands of Native cultural artifacts and the remains of deceased Indigenous people — also known as our ancestors.”

He notes that while museums are making moves to comply with NAGPRA’s updated rules, some conservatives criticize the rules as part of the so-called “woke” or liberal political agenda and accuse the Interior Department of erasing Indigenous history.

“If conservative columnists, politicians and benefactors truly want to ensure that Native Americans are not erased, they should stop ‘fixating on our ancestors’ bones” and instead focus on honoring treaties and funding health care and education to ensure Native Americans can live ‘in modest prosperity.’”

Read the editorial here:

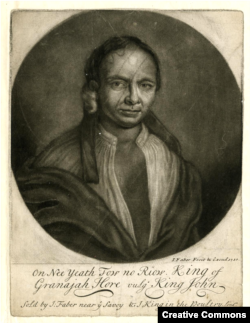

Portrait of 18th-century Mohawk diplomat scores big at auction

An engraved portrait of early Mohawk leader Ho Nee Yeath Taw No Riow fetched nearly $39,000 at auction on Sunday. Engraved by London printmaker John Faber the Elder, it depicts a sachem also known as John of Canajoharie (New York), who was one of a delegation of four Haudenosaunee political representatives who in 1709 set sail for London to negotiate an alliance against the French in the Great Lakes region.

In London, the so-called “Four Kings” — three Mohawk sachems and a Mahican — were wined, dined and celebrated in style.

The engraving was part of an extensive collection of prints by Old Masters collected by wealthy 19th-century Arlington, Massachusetts, citizen Winfield Robbins. Fearing that photography would eventually replace the Old World arts of printmaking, Robbins spent years abroad amassing a collection of tens of thousands of prints and other works of art.