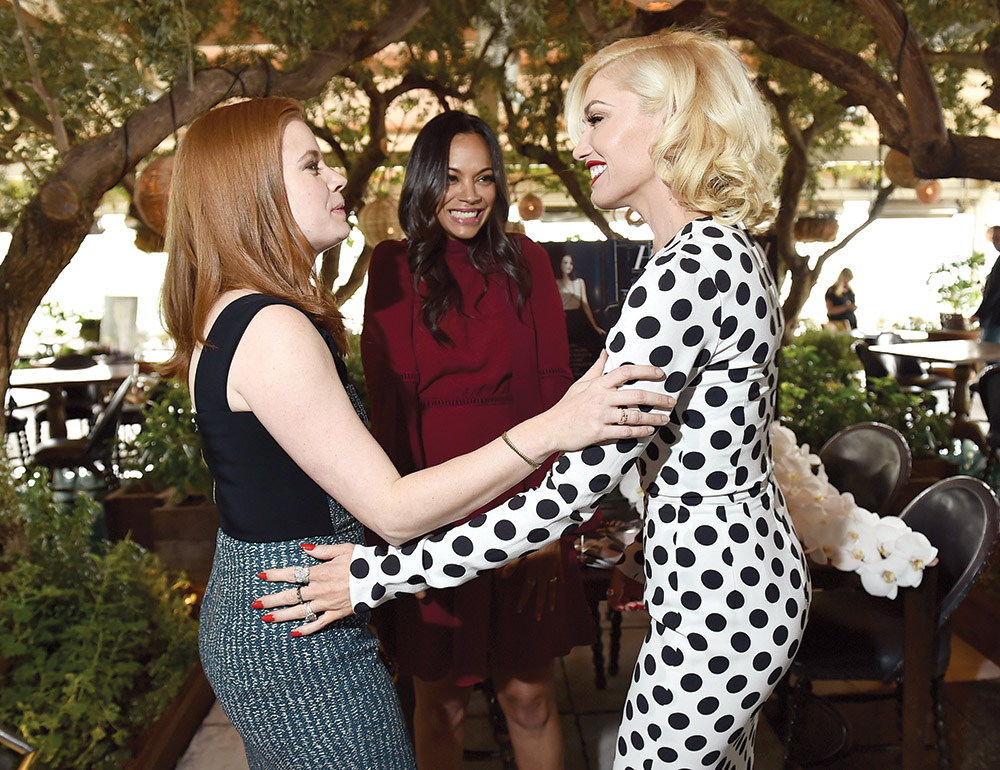

From left: Amy Adams, Zoe Saldaña and Gwen Stefani at Soho House West Hollywood for THR’s Most Powerful Stylists event in 2015.

Jordan Strauss/Invision for The Hollywood Reporter/AP Images

When, in a Feb. 7 report, short-sellers eviscerated Soho House — pronouncing it “a zero,” prophesying it would “meet the same fate” as notorious IPO flameout WeWork — the company’s crisis of cool had already been years in the making. The publicly listed private members club, a seeming oxymoron bearing the sticker symbol SHCO, has for years faced brickbats about how it shed its exclusive appeal: It morphed from a Hollywood-favored hangout with just a few outposts in London, Manhattan and Los Angeles into an international empire of 42 locations with a quarter million dues-paying clients. But now, along with serious allegations about its accounting and critiques of its debt levels, the club is also fending off mortifying questions about overexpansion, overcrowding and brand dilution.

Soho House, now known even to your small-town aunt as the place Prince Harry met Meghan Markle, owes much of its runaway success to conjuring spaces for the creative class that are so enticing that far less fashionable finance folks became desperate to join. In fact, the subtext of much of its growth narrative was the anxious management of this modish-to-monied ratio. Yet three years after the company went public on the New York Stock Exchange, its share price is languishing at $5.88 as of March 5, down 58 percent from its debut. Ironically, the business is caught between the suits in charge of it and the suits who aim to kill it — in no small part by highlighting that the club has long since been inundated by too many suits.

Nick Jones founded Soho House nearly three decades ago in the London neighborhood that gives the business its name. It quickly became an insiders’ hub for the BAFTA set (the Welsh actor Matthew Rhys was on the club’s membership committee when he was 24), as well as a crossroads for fashion, art, music and media. It was seen as the hipper, edgier alternative to entrenched establishment clubs like Annabel’s and White’s. Soho House’s flashbulb moment among around-the-world normies, though, may have been in 2002, when it was reported that Jude Law’s toddler accidentally swallowed an ecstasy tablet at a kids’ party there. These days, there are child memberships and licensed nursery services.

The club arrived in Manhattan the next year, benefiting from a key cameo in Sex and the City, and then, after hosting six years of Oscar pop-ups at sites like Merv Griffin’s former home, it debuted to instant fanfare in 2010 atop a Sunset Strip tower among industry players who came to treat it as a shared living room, from then-HBO boss Michael Lombardo to Amy Adams, who raved about the “enchanting” space to The Hollywood Reporter in 2015.

From left: Amy Adams, Zoe Saldaña and Gwen Stefani at Soho House West Hollywood for THR’s Most Powerful Stylists event in 2015.

Jordan Strauss/Invision for The Hollywood Reporter/AP Images

At the outset, Soho House West Hollywood denied the likes of Kim Kardashian and Real Housewives stars and promised to enforce a no-assholes rule for agents and executives. Before her Hollywood career, Euphoria producer Ashley Lent Levinson ran cultural programming there, including a live reading of the Shampoo script with Warren Beatty, a storytelling session with Bob Evans and an intimate Prince show. Now, in L.A. alone, there are four clubs, including a Malibu beach house, and Soho House has expanded beyond cities to countryside estates with pigeon shooting and horseback riding. The company also owns stand-alone restaurants (including Cecconi’s) and hotels (The Ned), as well as Soho Home — an interior design and household goods business to capitalize on its widely coveted aesthetic.

Jones, the founder, sold 80 percent of the club in 2008 to British hospitality impresario Richard Caring (who also owns Annabel’s). Four years later, billionaire investor Ron Burkle paid $250 million to acquire 60 percent of Soho House, with Caring holding 30 percent and Jones retaining 10 percent. The trio remain controlling shareholders of the public company.

The Little Beach House Malibu is one of four Soho House locations in Los Angeles.

DAVE BURK/Courtesy of Soho House

There’s little, if any, known precedent for a corporation quite like Soho House becoming a listed stock. “We believe that we are the only company to have pioneered and scaled a private membership platform with global presence,” it explained in an SEC registration statement for its 2021 IPO. The company’s CEO, Andrew Carnie, said at the time that the main reason for becoming a listed firm was to pay down debt — “We don’t really need it for capital investment,” he told The New York Times.

The Feb. 7 report attacking the club’s business model was published by an obscure financial research outfit called, as it happens, GlassHouse. This entity tells THR it represents the interests of a decentralized group of short-sellers and is supported by financial analysts and accountants. The firm has been producing such reports since 2016 on everything from construction companies and technology firms to medical businesses.

Short-sellers — some public, like Bill Ackman, but most clandestine — often employ a shared strategy, both cynical and potentially effective. They short a stock with the expectation it’ll be a loser, and often with the intent to tank its value. One of the ways this can occur is by releasing damaging information, such as the material produced by GlassHouse, which can then scare off would-be investors and convince owners to sell their shares. That then opens the chance of a payday for the short-sellers.

Citing personal safety concerns, a GlassHouse principal agreed to speak to THR only if his identity was withheld. “This can be a dangerous game,” says the short-seller, who identified himself as Wes. “When you short stocks, you get things like death threats. When people have invested millions in a company and it falls $20 million and they lose millions, they don’t react well.” He noted that Soho House came across GlassHouse’s radar as the result of multiple red flags, including its cash flow mechanisms, which it believes can be easily manipulated.

Soho House West Hollywood is in the penthouse of this Sunset Strip tower.

Google Street View

The GlassHouse report called out Soho House for alleged poor accounting measures, climbing debt and financial shortfalls. Those claims ricocheted throughout the finance world and then on to the very members who pay thousands of dollars every year in dues. In response, Soho House said it was buying back shares and exploring a potential sale, which would result in the company being private once again.

GlassHouse makes the case in the report that a “persistent lack of profits and rising debt levels put the company in a precarious situation where they will need to continue to dump shares on investors as time goes on.” The firm added that Soho House was “never profitable in its 28-year history, went public to dump on retail investors, all while its debt surged to insurmountable levels.” And in a statement clearly designed to attract headlines, GlassHouse stated that the situation is “eerily similar to WeWork’s public offering [and] we believe Soho House & Co will eventually meet the same fate.” (In response to the report, multiple law firms have announced investigations toward potential claims on behalf of the company’s investors.)

Founder Nick Jones (left) and controlling shareholder Ron Burkle.

Courtesy of Business Wire; Jon Kopaloff/Getty Images

According to Soho House, as of fall 2023 — the end of the third quarter — it had a cash position of $163 million. The company is quick to point out its cash flow from operating activities for the first nine months of the year was $30.5 million, compared to WeWork’s $530 million in the red.

The GlassHouse report called it “troublesome” that since going public Soho House had not shared its member retention rate on a quarterly basis when this had previously been a mainstay in company presentations. “The rapid expansion of Soho House’s membership base and global footprint raises worries about the potential dilution of the exclusive experience and member satisfaction,” GlassHouse wrote. However, Soho House has explained that its retention rate was 93 percent as of the end of 2022 and boasts that as of the third quarter of 2023, it has an all-time high of 98,000 people on a wait-list to become members.

Soho House had been expected to provide updated numbers March 6 but announced a last-minute delay to March 15 to deliver its 2023 results.

It’ll be an opportunity for the company to further counter GlassHouse, whose report it has slammed in a press release as containing “factual inaccuracies, analytical errors, and false and misleading statements.” Soho House declined to make its executives available to THR, citing its quiet period ahead of earnings reports, but offered a statement it attributed to its CFO, Thomas Allen, which noted that “over the last 18 months, we have delivered on our strategy of growing membership and enhancing its value — through the service, food and drinks and events in our Houses — and driving operational excellence to support greater profitability.”

The interior of Soho House Stockholm, part of an aggressive ongoing global expansion effort. Four more locations have been announced.

Dana Ozollapa/Courtesy of Soho House

Predictably, GlassHouse’s report prompted knives-out media coverage. A New York Post story quoted anonymous detractors carping about the Meatpacking District location that the “vibe is off” and “you need a flare gun to get a waiter’s attention.” Not that the Powers That Be at Soho House would disagree. In a Dec. 8 letter to members, Jones, who now serves as director of the board, wrote that he’d been spending “a lot more time” at the worldwide outposts, hearing from members and employees. “We continue to be very focused on improving service,” he said, “as well as making sure our Houses don’t feel too busy.” Jones claimed new members will not be accepted in 2024 at properties in London, New York and L.A., and only at “locations where we have capacity.”

Jones had previously wielded a scythe when he felt the situation was dire: In 2010, he told the Post that he’d culled hundreds of “corporate types” from the same Meatpacking District property in Manhattan, explaining he was “trying to get the club back to its creative roots,” and adding that “it’s all about the right mix.” How, or if, this was executed is unclear.

Inside the Soho House Oscar Villa in February 2005

Kevin Winter/Getty Images

“Probably one of the reasons they aren’t profitable is they want exclusivity, but they need bodies through the door to pay the bills,” Wes at GlassHouse tells THR. “The ‘corporate type’ pays the membership and they don’t care. Soho House wants starving artists that don’t have the money. If they were profitable, maybe this could work, but nothing in the financials shows us this business model can work long-term.”

Soho House pointed THR to analysts who dismissed GlassHouse’s gloominess, some of whom worked at financial firms that shepherded the company’s IPO. Another institution, the privately held investment bank Roth MKM, wrote in a rebuttal: “We believe that most claims from the report regarding the business model and accounting practices are misinformed and/or overreactions, and that SHCO’s debt burden is manageable given the company’s improving profitability and ‘monetizable’ non-core assets.” Still, Roth MKM acknowledges that Soho House is burdened by over $600 million of net debt, which it describes as “substantial.”

Columbia business professor Silvia Bellezza, whose research focuses on luxury marketing, believes that Soho House has a legitimate theory of brand expansion — members in the early transatlantic cities gain access to a more varied global network of peers, from Mumbai to, soon, São Paulo. Yet it’s tough to scale. When the doors swing too wide open, Bellezza points out, “it’s easier to get into the club, and that’s a loss of exclusivity, which is a large part of what people believe they’re buying.”

Soho House now operates 42 international locations, including Soho House Mexico City

Fernando Marroquin/Courtesy of Soho House

Chekitan S. Dev, a professor specializing in luxury hospitality branding at Cornell’s business school, notes that the promise implicit in a club like Soho House is that it “keeps the riffraff out,” and “it’s a delicate alchemy to maintain as a public company because they grow or die. So, sometimes they compromise in their relentless pressure to grow, and they’re not what they were.” He says Soho House benefited early by being a first mover, but now “other businesses are invading its brand space” as it fights wised-up competition. In Los Angeles alone, it’s competing not just with direct copycats and newer, more exclusive options like San Vicente Bungalows, but also with adjacent concepts: co-working space NeueHouse, ultra-high-end gym Heimat and the Pendry hotel’s members-only spot The Britely.

Former LVMH North America chair Pauline Brown, who has taught on the global business of aesthetics at Harvard Business School, says she believes that “if they’re lucky, they’ll go private, given their exposure in the public markets and their debt load. Otherwise, they’re in a bit of a doom loop. A business like this shouldn’t have been a stand-alone public company.”

This story first appeared in the March 6 issue of The Hollywood Reporter magazine. Click here to subscribe.