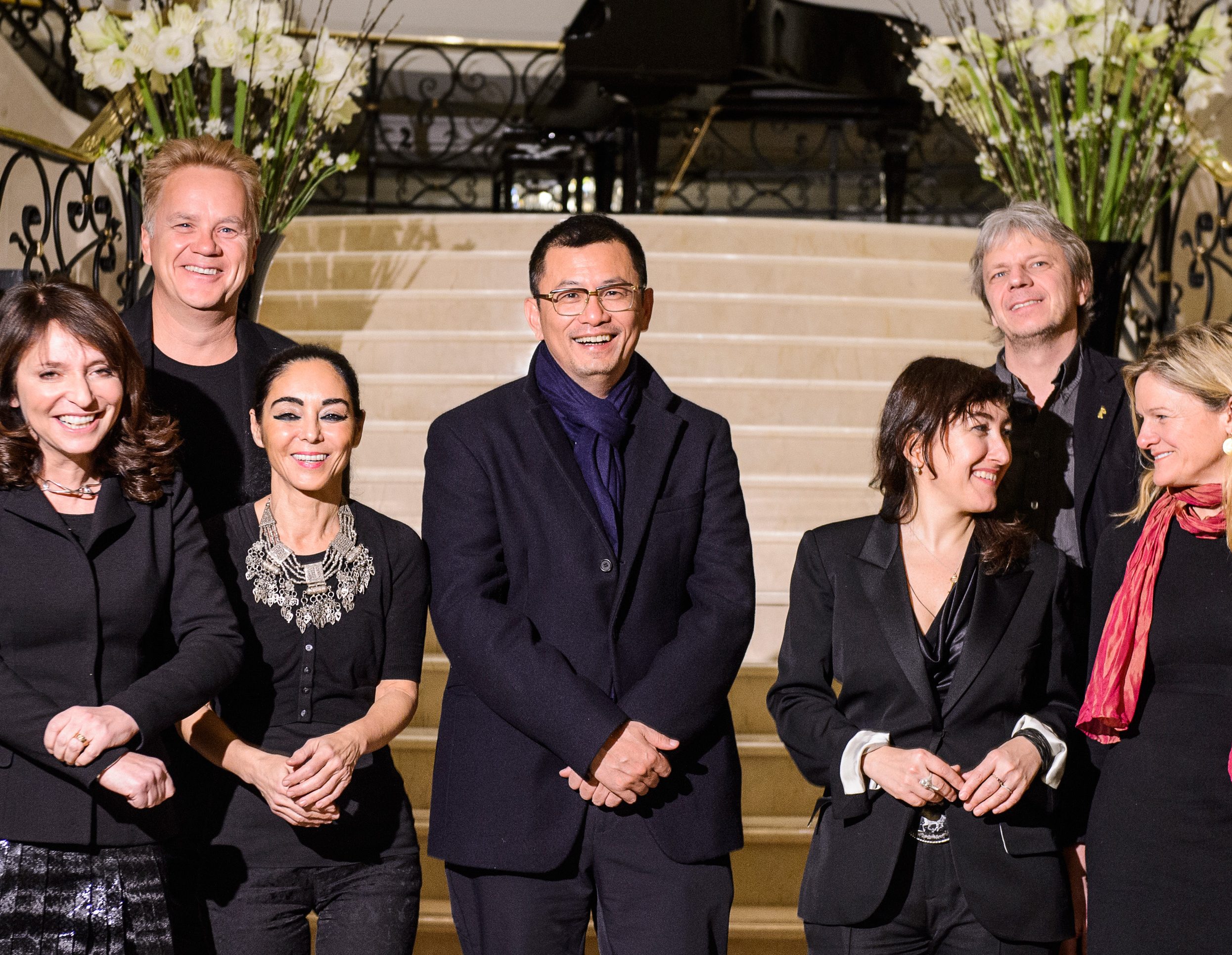

A pre-Currywurst photo of the international jury of the 2013 Berlinale.

Alexander Janetzko ©Berlinale 2013

Andreas Dresen‘s favorite Berlinale memory, as you’d expect, involves Currywurst.

“I was on the jury one year, And it was clear I was the local guy among all these big names,” he recalls. “Now the festival had a vegan menu already then, and at the awards dinner, we had great food but they were quite small portions and [jury president] Wong Kar Wai turns to me and says ‘Andreas, can’t we get some real food?’ So I took them all, Susanne Bier, Shirin Neshat, Tim Robbins, everyone in tuxes and evening gowns, to [legendary Berlin snack bar] Curry 36 for a Currywurst. Even Tim Robbins, who actually is vegetarian, tucked in. I personally saw him gobble up three Currywursts. It was the most Berlin moment ever.”

Dresen has had a few. The 60-year-old director has been a regular at Germany’s top film festival since 1991 when his student film So schnell es geht nach Istanbul premiered in the fest’s Forum section. There he met Wolfgang Pfeiffer, who produced his feature debut, Silent Country. His follow-up, Night Shapes, was in the Berlin competition in 1999 and won the Silver Bear for best actor for star Michael Gwisdek. Since then, he’s had four more films in competition — including this year’s Golden Bear contender From Hilde, With Love — as well as screening documentaries in Panorama and serving on multiple juries.

A pre-Currywurst photo of the international jury of the 2013 Berlinale.

Alexander Janetzko ©Berlinale 2013

“The Berlinale’s a bit like my second living room,” says Dresen. “I really know the festival inside out, from every possible perspective.”

Currywurst with Tim and Wong aside, an absolute Berlinale highlight for Dresen came in 2002 when Grill Point won the Grand Jury prize. The low-budget dramedy about two couples living in a small city on the Polish border was completely improvised.

“It was a very special story because Grill Point was ridiculously low-budget, almost an experimental movie,” says Dresen. “We didn’t expect it to come out at all, let alone go to the Berlinale. Then we got into competition and the premiere was one of the most impressive I’ve ever seen. It was on Tuesday afternoon, I think, and the room literally exploded. At the awards ceremony, when we won, I brought the entire team on stage – all the actors and the entire crew – and we were 12 people total.”

Dresen, who never uses the “a film by” credit in his movies – “I hate that formulation because a film is made by a team,” he says – made an exception with Grill Point, listing everyone’s name, from leads to grips, involved in the picture.

Andreas Dresen with the entire cast and crew of 2002 Berlin Silver Bear winner ‘Grill Point’

©Berlinale 2013

The German director’s work often oscillates between semi-improvised, near-documentary-style dramas, like Grill Point, Cloud 9, and Stopped on Track – the later both Cannes premieres, winning the jury prize and best film, respectively, in Un Certain Regard in 2008 and 2011 – and more tightly-scripted fare from his regular collaborations, the late Wolfgang Kohlhaase (who penned Summer in Berlin, Whiskey With Vodka and 2015 Berlinale competition entry As We Were Dreaming) and Laila Stieler, screenwriter on 2005 crime thriller Willenbrock, 2018 period drama Gundermann about Gerhard Gundermann, East Germany’s answer to Bob Dylan, and Rabiye Kurnaz vs. George W. Bush, which won the Berlinale Silver Bear in 2022 for star Meltem Kaptan as the titular Turkish housewife who takes on the U.S. government to free her son from his illegal imprisonment in Guantanamo Bay.

Alexander Scheer and Meltem Kaptan in ‘Rabiye Kurnaz vs. George W. Bush.’

Courtesy of Andreas Hoefer / Pandora Film

Stieler also wrote the screenplay for Dresen’s latest, From Hilde, With Love, which features Babylon Berlin star Liv Lisa Fries in the real-life tale of Hilde Coppi, a left-wing resistance fighter who was executed by the Nazis in 1943.

But Dresen is quick to note that his scripted films also involve a lot of improvisation — “for the big scene with Hilde on death row when she dictates her farewell letter, I gave Liv Lisa Fries complete freedom in how she wanted to do it, we shot the scene all day, and each take was 10-12 minutes long, her doing different things every time,” he notes. Even his near-documentary movies have carefully staged moments. In Grill Point, there’s a recurring joke where downtrodden protagonist Uwe (Axel Prahl) keeps stumbling across a group of buskers, who appear to multiply with each encounter. (The buskers, played by German folk ensemble 17 Hippies, actually outnumbered the film’s entire crew.)

Born and raised in Eastern Germany, and a filmmaker who has always made his working-class and left-wing alliances a point of pride, Dresen is most often compared to British social realist legend Ken Loach. While there are similarities — “I’m a total fan of Loach, how he tells stories of so-called ordinary people with such humor and heart, while remaining political,” he says — branding Dresen “the German Ken Loach” would be unfair and reductive. Loach has yet to make an explicitly erotic dramedy about a senior citizen experiencing the 30-year-itch (as Dresen did with Cloud 9) or a kids’ film based on a German fairytale (Dresen 2017’s The Legend of Timm Thaler or The Boy Who Sold His Laughter).

“I always want to try something different, something I haven’t done before,” says Dresen. “After the success of Grill Point, everyone wanted Grill Point 2, the same sort of thing, but I hate repeating myself. So my next film was a documentary about a German politician (2003’s Vote for Henryk!) then a crime thriller (2005’s Willenbrock).”

He will be following up From Hilde, With Love, a powerful, if often harrowing story of love and resistance from the darkest period of German history, with Auguste, the Christmas Goose, a remake of an East German holiday classic from 1988.

“After Hilde, it felt right to do a nice family film again,” he admits.

The director’s versatility has made him hard to pigeonhole, much less market, as an arthouse “brand” along the lines of Loach or Aki Kaurismäki (another of Dresden’s favorites).

His films vary widely in mood and style — from the gritty kitchen-sink realism of Grill Point and Stopped on Track, the story of a man dying of brain cancer — to period films Hilde and Gundermann — the latter examines how the German Democratic Republic’s secret police service, the Stasi, infiltrated every aspect of its citizens lives, even the most intimate — to the Erin Brockovich-esque docu-drama of Rabiye Kurnaz vs. George W. Bush.

(from left): actor Alexander Scheer, director Andreas Dresen and actress Meltem Kaptan at the photo call for ‘Rabiye Kurnaz vs. George W. Bush’ at the 2022 Berlinale

© Ali Ghandtschi / Berlinale 2022

The history of East Germany often plays a central role in Dresden’s movies, but he avoids both the “Ostalgie” (East Nostalgia) of films like Wolfgang Becker’s Goodbye Lenin, “which paints East Germany as a kooky place with funny cars and odd objects,” he noted, in an interview with Senses of Cinema in 2009, or the “Hollywood fairy tale” of sinister Stasi agents in black coats as seen in Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck’s The Lives of Others. “I’m not saying these are bad films but for me, they have relatively little to do with the GDR or GDR history… most Stasi agents had families; they lived perfectly normal, ordinary lives, having BBQs on the weekends with friends in their dachas, and on Monday they went back to the office and denounced people.” (Both Becker and von Donnersmarck are “Wessies,” German for people from West Germany).

From Hilde, With Love is also a very inside look at Eastern German history. Though barely known in the West, Hilde Coppi was an iconic figure in East Germany, one of the “absolute superheroes” of the Communist resistance, branded the “Red Chapel” by the Nazi Gestapo. Together with her husband Hans and a small group of mostly socialist and communist-leaning activists, they tried to counter Nazi propaganda with anti-fascist flyers, clandestine protests, and pirate radio broadcasts, including transmitting messages, from Radio Moscow, of German war prisoners to their families back home. (Hitler’s propaganda claimed the Soviets took no prisoners, but shot every soldier on sight.)

“They were put on such a pedestal in the East, made to seem so brave, so incredibly strong, which I think had a very political intention behind it,” says Dresen. “Because when you have people so great, so superhuman, you can’t ever imagine yourself rising to their level, to be that brave. You can’t imagine yourself fighting the system the way they did. But what I found interesting about the real Hilde Coppi, is that she wasn’t a superhero. She’d never even have claimed to be a resistance fighter. She was just someone who followed her heart and did what she thought was right.”

‘From Hilde, With Love’

c-Pandora-Film-Produktion_Frederic-Batier

The story of From Hilde, With Love is thus a more ordinary, and more moving and powerful tale of human decency.

Dresen cross-cuts the depiction of Hilde’s arrest, imprisonment — she gave birth to her son while in a Gestapo jail — and eventual beheading by the Nazis, with Hilde and Hans’ relationship, the first summer they met and fell in love.

“And had sex!” Dresen chuckles. “I don’t know if you’ve ever noticed watching films about resistance fighters, but apparently, they never had sex. I guess between all that pamphleting and being heroic and fighting Fascism and all, they just didn’t have time.”

By balancing the light of Hilde Coppi’s life with the darkness of its end, Dresen finds hope and humanity in the midst of the horror. There are no monsters here — even Hilde’s Nazi guards treat her kindly and complain about the injustice of her trial — only flawed ordinary people, some braver than others.

“There are some pure assholes in the world, but I rarely put them in my movies,” says Dresen. “I try to find the good in everyone.”

In other words: there’s no one Andreas Dresen wouldn’t share a Currywurst with.