Antiwar politician Boris Nadezhdin was rejected Thursday as a candidate in next month’s presidential balloting by Russian election authorities, a strong signal from the Kremlin that it would tolerate no public opposition to the invasion of Ukraine.

The move by the Central Election Commission provides an even smoother path for President Vladimir Putin to win a fifth term in power. He faces only token opposition from pro-Kremlin candidates in the March 15-17 vote and is all but certain to win, given his tight control of Russia’s political system.

Nadezhdin, a local legislator in a town near Moscow, had needed to gather at least 100,000 signatures of supporters — a requirement that applies to candidates of political parties that are not represented in the Russian parliament.

The Central Election Commission declared that more than 9,000 signatures submitted by Nadezhdin’s campaign were invalid, which was enough to disqualify him. Russia’s election rules say potential candidates can have no more than 5% of their submitted signatures thrown out.

Nadezhdin, 60, has openly called for a halt to the war in Ukraine and for starting a dialogue with the West. Thousands of Russians lined up across the country last month to sign papers in support of his candidacy, an unusual show of opposition sympathies in the country’s rigidly controlled political landscape.

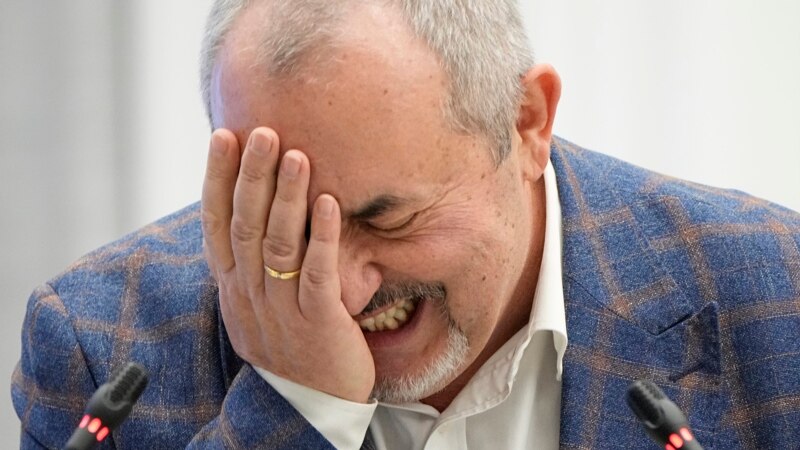

Speaking to officials at the election commission on Thursday, Nadezhdin asked them to postpone their decision, but they declined. He said he would appeal his disqualification in court.

“It’s not me standing here,” Nadezhdin said. “Hundreds of thousands of Russian citizens who put their signatures down for me are behind me.”

Putin is running as an independent candidate, and his campaign was required to gather at least 300,000 signatures in his support. He was swiftly allowed on the ballot earlier this year, with election officials disqualifying only 91 out of 315,000 that his campaign submitted.

Most of the opposition figures who might have challenged Putin have been either imprisoned or exiled abroad, and the vast majority of independent Russian media outlets have been banned.

Three other candidates registered to run were nominated by parties represented in parliament and weren’t required to collect signatures: Nikolai Kharitonov of the Communist Party, Leonid Slutsky of the nationalist Liberal Democratic Party and Vladislav Davankov of the New People Party.

The three parties have been largely supportive of the Kremlin’s policies. Kharitonov ran against Putin in 2004, finishing a distant second.

Exiled opposition activists threw their weight behind Nadezhdin last month, urging their supporters to sign his nomination petitions.

Putin spokesman Dmitry Peskov has said the Kremlin doesn’t view Nadezhdin as “a rival.”

Nadezhdin urged his supporters not to give up despite the setback.

“One thing happened which many could not believe: citizens sensed the possibility of changes in Russia,” he wrote in an online statement. “It was you who stood in long lines to declare to the whole world: ‘Russia will be a great and a free country.’ And I represented each of you today in the auditorium of the Central Election Commission.”

Nadezhdin is the second antiwar hopeful to be denied a place on the ballot. In December, the election commission refused to certify the candidacy of Yekaterina Duntsova, citing problems such as spelling errors in her paperwork.

Duntsova, a journalist and a former legislator from the Tver region north of Moscow, had announced plans last year to challenge Putin. Promoting a vision of a Russia as “peaceful, friendly and ready to cooperate with everyone on the principle of respect,” she said she wanted to end the fighting in Ukraine swiftly and for Moscow and Kyiv to come to the negotiating table.

Abbas Gallyamov, a former Putin speechwriter who became a political analyst, said the decision to keep Nadezhdin off the ballot showed how hollow the support for Putin was.

“All of Putin’s mega-popularity, which official sociology constantly broadcasts, all that ‘rally around the national leader’ that Peskov regularly talks about is, in fact, a highly artificial and unstable structure that does not withstand any contact with reality,” he said.