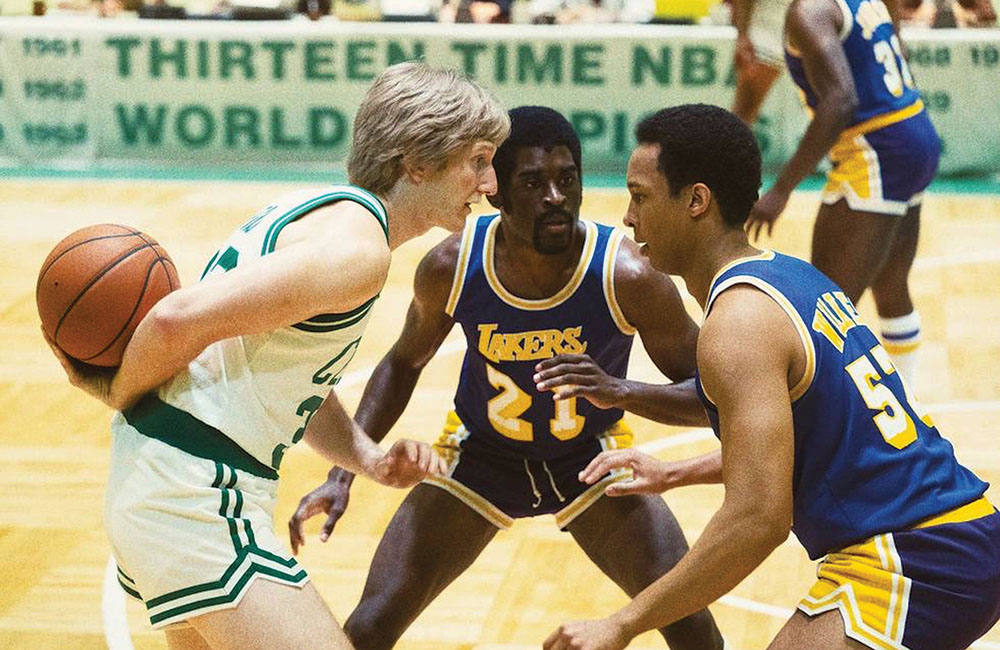

Sean Patrick Small as Larry Bird, Delante Desouza as Michael Cooper and Jimel Atkins as Jamaal Wilkes.

Courtesy of Warrick Page/HBO

Considering it’s a show about one of the greatest basketball teams ever, it makes sense that the people operating behind the scenes of HBO’s Winning Time: The Rise of the Lakers Dynasty had to function like a coaching staff, getting veteran actors John C. Reilly and Adrien Brody to work alongside breakouts like Quincy Isaiah and Solomon Hughes. But nobody had to actually coach quite like trainer Idan Ravin, who can normally be found helping NBA stars like LeBron James and Stephen Curry refine their skills. Getting actors to turn in a great performance was one thing, but as co-creator Max Borenstein and Ravin tell THR, pushing them to become good ballplayers was an entirely different challenge.

You always hear in sports how getting a team full of great veteran players and young, hungry players is always the best mix, and that’s what you did with Winning Time. Was it always the idea to have that pairing of Oscar winners with guys who had no IMDb credits?

MAX BORENSTEIN We got very fortunate in being able to cast such incredibly esteemed actors like John, Adrien and Sally [Field]. But when it came to casting [players], it was very clear early on that there was no well-known actor that we were familiar with or our casting agents were familiar with who would, for example, be the right Kareem [Abdul-Jabbar]. Because you needed someone who was really tall. You can’t fake a 7-footer — you can fake a few inches, but you can’t fake that. We knew there wasn’t a Kareem on the lists, and so that meant it had to be someone you hadn’t heard of. Our casting director looked far and wide with her team, and we got lucky with Solomon. With Magic [Johnson], it was the same thing. In addition to having a particular look and height, he also has to have that movie star charisma that’s really specific. It was really clear that we had to find people who were less well-known. Necessity was the mother of that.

When everything shut down during the pandemic, even the nets were removed from playground courts in L.A. How did you keep the actors engaged and training during all the downtime?

IDAN RAVIN I felt there had to be an almost spiritual, emotional connection to the project and something these young guys had dreamed about their whole life. All of a sudden, that had disappeared from their fingers because of COVID. I was able to do these virtual training sessions. We would meet literally almost every day and there would be talking and there’d be a connection. And yes, we were improving on their conditioning, on their athleticism, on their technique. But even more importantly, keeping them connected to a project.

Idan, you fill a role a choreographer might have on a musical, but you’re normally teaching real NBA players how to improve their game and not working with actors. How did you make it work?

RAVIN I felt fiduciary responsibility to deliver on the intent of the writer. I read hundreds of scripts before I even started on this project because I wanted to understand the structure and the writing and what goes into all of this. And then I spent a lot of time reading between the lines to understand what Max, [executive producer Rodney Barnes and co-creator Jim Hecht] really wanted to get from me. We would talk a lot beforehand, and Max would come up to set and give an idea of how he saw a particular scene. From there, we would refine it and refine it and refine it, and then create a certain pace to it and make sure it reflected the intent of the writers. It had to pop cinematically, it had to feel authentic. It had to feel memorable. It had to reflect the emotional beauty of the story. And it also had to fall within the capabilities of the actors.

Sean Patrick Small as Larry Bird, Delante Desouza as Michael Cooper and Jimel Atkins as Jamaal Wilkes.

Courtesy of Warrick Page/HBO

The game has changed a lot since the 1980s, and these actors grew up with Kobe Bryant and LeBron James. What was the biggest challenge in trying to get younger guys to seem like basketball players from 40 years ago?

RAVIN To me, the athleticism is the same, and you still need the baseline of technical skill. There were small things, little nuances, but that’s what sort of sells the character. The dribbling back then wasn’t as fancy, and guys didn’t jump off the ground like they do today, but they were still athletic. It’s almost like you had to take the Ferrari but dull it a little bit.

BORENSTEIN And how they celebrate. The high fives and the kinds of celebration you see today didn’t exist then. Magic Johnson claims to have brought the high five to the NBA.

After all this work, if you’re on a basketball court and you can either team up with the guys who play the Lakers on Winning Time or guys who ride the bench for a college basketball team, who are you going with?

RAVIN Max, I’m going to defer to you on this …

BORENSTEIN No, you go. You know teams better. (Laughs.)

RAVIN These guys are really good at performing their characters and delivering on their lines and delivering on the script. It’s still a work in progress for them to be dropping 50 in their men’s league game. I think the goal is for them to get really dope, so they’re all playing in the NBA All-Star Celebrity Game and dropping 45 and swagging it out. That’s the goal, but we’re still working toward that. Right now, I’ll probably pick the college basketball players.

Interview edited for length and clarity.

This story first appeared in the June 15 issue of The Hollywood Reporter magazine. Click here to subscribe.