In 1960, linguists predicted that compulsory education, mass media, foreign immigration and the “mobility of restless Americans” would ultimately standardize English, and in only a few generations, regional accents would disappear.

Today, some scholars such as University of Pennsylvania sociolinguist William Labov note that while some accents are fading, others are growing stronger.

One example, according to Kalina Newmark, is Native American English, more commonly referred to as the “rez accent,” found among many Indigenous communities in the United States and Canada. Rez is the shortened word for reservation.

Newmark, who is Dene and Metis from the Sahtu region of Canada’s Northwest Territories, attended Dartmouth College in Hanover, New Hampshire, a school well-known for its diverse, Indigenous student body.

“I’m a Dene person, but I don’t speak Slavey, my heritage language,” she said. “My mom can understand and speak it, but she didn’t pass it on to us. She learned it from her great-grandmother. My grandmother chose not to pass along the language because she wanted to make it easier for her children when they went to school.”

At Dartmouth, Newmark met Indigenous students from across North America and noticed an interesting phenomenon: Despite their different linguistic backgrounds, their English shared some distinctive features, especially when gathering socially. She found this was the case even with students who had never learned their heritage languages.

When assigned a project studying a non-English language, she and fellow Dartmouth student Nacole Walker, a Lakota from the Standing Rock Reservation in North and South Dakota, decided to investigate the rez accent, which had never been studied before.

“There are other kind of studies around different groups, like African-American vernacular English or Chicano English, where linguists have noted similarities. We knew something unique was happening [with indigenous English] and wanted to narrow it down,” Walker said.

The Dartmouth team interviewed and recorded conversations with 75 people from tribes and Nations across North America. Their findings, “The Rez Accent Knows No Borders: Native American Ethnic Identity Expressed Through English Prosody,” appeared in the journal Language in Society in September 2016.

They found that Native American and Canadian First Nations communities speak different English dialects, but many share similar patterns of pitch, rhythm and intonation — features that linguists call prosody, the “music” of language. Even students who did not use the rez accent were familiar with it.

“The most important feature we found is the ‘contour pitch accent,’” said Dartmouth sociolinguist James Stanford, who mentored their study. “We called it the ‘Thomas’ feature.”

It refers to the character Thomas Builds-the-Fire, played by actor Evan Adams in the groundbreaking 1998 film Smoke Signals, the first commercial feature film to be written, directed and acted by Indigenous people. Thomas, an incessant storyteller living on the Coeur D’Alene Indian Reservation in Idaho, speaks in an exaggerated rez accent. His intonation rises and falls melodiously (see a clip from the film, below).

“Another feature [that] study participants identified as ethnically distinctive had to do with what we call mid- or high-rise terminals,” said Stanford.

In standard English, Stanford explained, speakers’ voices tend to drop in pitch at the end of a sentence. Many Indigenous speakers — like the character Thomas — end their sentences on a middle or high pitch.

“One other important feature that we noted was syllable timing — or rhythm,” Stanford said. “Each syllable takes up the same amount of time.”

These prosodic features can be heard in the three YouTube videos below.

‘Whispers’ of the ancestors

Though she doesn’t discredit the influence of individual heritage accents, Newmark believes the rez accent is rooted in intertribal contact that took place during the reservation era of the 1880s, when Native and First Nations children from diverse language backgrounds were forced into residential schools, or during the relocation era of the 1950s and 1960s, when the U.S. sought to move Native Americans to cities and terminate reservations.

Coming together in schools or urban communities, Native Americans were compelled to interact with one another in English.

“They were all learning English together,” said Newmark, “and making an English of their own.”

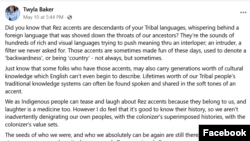

“What we are seeing is adaptation — and Native Americans have been specialists at adaptation forever,” said Twyla Baker, a citizen of the Mandan, Hidatsa and Arikara Nation (MHRA) and president of Nueta Hidatsa Sahnish College on the Fort Berthold Reservation in North Dakota.

She pointed out that before contact with Europeans, tribes did not live in vacuums.

“We traveled. We engaged in trade. We intermarried. We built political alliances with other tribes,” Baker told VOA. “The ability to learn other languages was crucial, and it wasn’t uncommon for folks to speak four or five languages, as many Europeans do today.”

She is aware that some people, Native and non-, poke fun at the rez accent, or dismiss it as “improper English.”

“One of my big goals as an educator is to knock down this idea, which was imposed upon us that we should be ashamed of who we are, where we came from, how we speak English and how we present ourselves in a very Westernized society,” Baker said. “I would love for our young people to feel that they are accepted not just in the spaces that they occupy in Indian Country, but when they step off the reservation.”