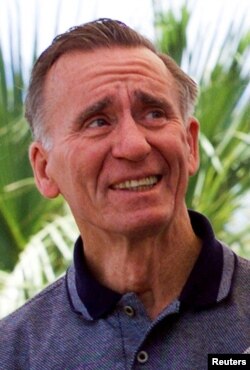

Walter Cunningham, the last surviving astronaut from the first successful crewed space mission in NASA’s Apollo program, died Tuesday in Houston. He was 90.

NASA confirmed Cunningham’s death in a statement but did not include its cause. Spokespersons for the agency and Cunningham’s wife, Dot Cunningham, did not immediately respond to questions.

Cunningham was one of three astronauts aboard the 1968 Apollo 7 mission, an 11-day spaceflight that beamed live television broadcasts as they orbited Earth, paving the way for the moon landing less than a year later.

Cunningham, then a civilian, crewed the mission with Navy Capt. Walter M. Schirra and Donn F. Eisele, an Air Force major. Cunningham was the lunar module pilot on the space flight, which launched from Cape Kennedy Air Force Station, Florida, on October 11 and splashed down in the Atlantic Ocean south of Bermuda.

NASA said Cunningham, Eisele and Schirra flew a near perfect mission. Their spacecraft performed so well that the agency sent the next crew, Apollo 8, to orbit the moon as a prelude to the Apollo 11 moon landing in July 1969.

The Apollo 7 astronauts also won a special Emmy award for their daily television reports from orbit, during which they clowned around, held up humorous signs and educated earthlings about space flight.

It was NASA’s first crewed space mission since the deaths of the three Apollo 1 astronauts in a launch pad fire January 27, 1967.

Cunningham recalled Apollo 7 during a 2017 event at the Kennedy Space Center, saying it “enabled us to overcome all the obstacles we had after the Apollo 1 fire and it became the longest, most successful test flight of any flying machine ever.”

Cunningham was born in Creston, Iowa, and attended high school in California before enlisting with the Navy in 1951 and serving as a Marine Corps pilot in Korea, according to NASA. He later obtained bachelor’s and master’s degrees in physics from the University of California at Los Angeles, where he also did doctoral studies, and worked as scientist for the Rand Corporation before joining NASA.

In an interview the year before his death, Cunningham recalled growing up poor and dreaming of flying airplanes, not spacecraft.

“We never even knew that there were astronauts when I was growing up,” Cunningham told The Spokesman-Review.

After retiring from NASA in 1971, Cunningham worked in engineering, business and investing, and became a public speaker and radio host. He wrote a memoir about his career and time as an astronaut, “The All-American Boys.” He also expressed skepticism in his later years about human activity contributing to climate change, bucking the scientific consensus in writing and public talks, while acknowledging that he was not a climate scientist.

Although Cunningham never crewed another space mission after Apollo 7, he remained a proponent of space exploration. He told the Spokane, Washington, paper last year, “I think that humans need to continue expanding and pushing out the levels at which they’re surviving in space.”

Cunningham is survived by his wife, his sister Cathy Cunningham, and his children Brian and Kimberly.