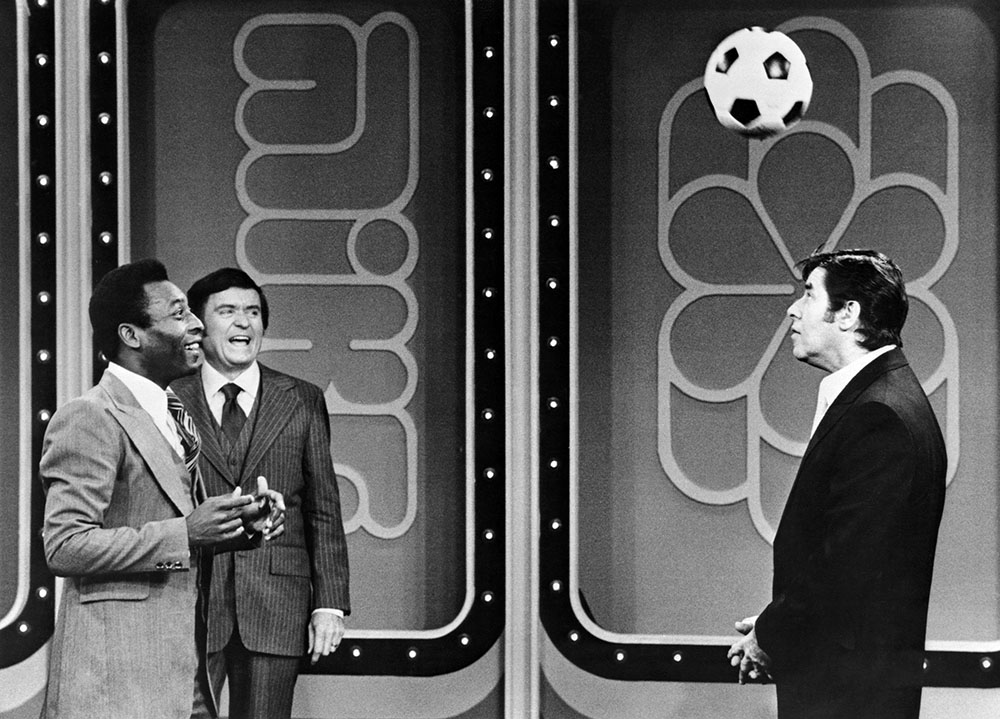

From left: Pelé appeared on ‘The Mike Douglas Show’ in 1978 with the host and Jerry Lewis.

Everett

Pelé, the Brazilian national treasure who in the 1960s and ’70s made soccer popular in places on the planet that hadn’t yet embraced the “beautiful game” — in particular the U.S. — has died. He was 82.

An unequaled hero of fútbol, Pelé died Thursday, his agent told The Associated Press, after being hospitalized in Sao Paolo, Brazil, for the past month. He was diagnosed with colon cancer in September 2021.

His daughter, Kely Nascimento, posted a tribute to her father on Instagram.

Pelé burst onto the international stage during the 1958 World Cup tournament, where he scored three goals in a semifinal match and two more in the final at the age of 17, capping a brilliant and emotional victory for the Brazil national team. He would win two more World Cup titles before joining the New York Cosmos in the North American Soccer League in 1975.

He remains the only player in history to play on three world champion teams, an amazing feat considering 140 countries vie for the World Cup every four years.

In 1969, Brazil issued a postage stamp with Pelé’s image in celebration of his 1,000th goal, and FIFA in 1999 named him its Co-Player of the Century along with the late Diego Maradona of Argentina, the same year the International Olympic Committee voted him Athlete of the Century. In 1970, a then-unparalleled 900 million viewers watched Pelé in his last televised World Cup game.

Even political statesmen remarked on his skill and his influence. “To watch him play was to watch the delight of a child combined with the extraordinary grace of a man in full,” former South Africa president Nelson Mandela said in 2000.

“Heroes walk alone, but they become myths when they ennoble the lives and touch the hearts of all of us. For those who love soccer … Pelé is a hero,” former U.S. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger wrote in Time magazine in 1999.

“My name is Ronald Reagan, I’m the president of the United States. But you don’t need to introduce yourself, because everyone knows who Pelé is,” Reagan joked when meeting him in the 1980s. And artist Andy Warhol once remarked, “Pelé was one of the few who contradicted my theory: Instead of 15 minutes of fame, he will have 15 centuries.”

In 1967, at perhaps the height of his popularity, a 48-hour cease-fire was declared during the Nigerian Civil War so that both sides could watch Pelé play when he visited the war-torn African nation. Years later, a former Brazilian ambassador to the U.N. said that during the years Pelé played, “he did more to promote world friendship and fraternity than any other ambassador anywhere.”

In the introduction to Pelé’s 1977 autobiography, My Life and the Beautiful Game, Robert Fish puts the athlete’s popularity into perspective: “More people have seen him play football than any other athlete in any sport, anywhere, at any time. More people know his name and face than any other person who has ever lived; he has been photographed more than any person in history, including movie stars and statesmen. He has visited 88 countries, has met with 10 kings, five emperors, 70 presidents and 40 other chiefs of state, including two popes. He is an honorary citizen of more cities and countries than any person in history.”

Like many athletes of his caliber, Pelé also dabbled in acting, largely playing himself, such as when he co-starred in Hotshot, a 1987 movie about an American soccer player who seeks his advice. He also wrote and produced a few foreign films and appeared in the 1981 Sylvester Stallone movie Escape to Victory. A singer and musician, he even composed the soundtrack to the 1977 movie Pelé.

In 2016, Imagine Entertainment’s Brian Grazer produced Pelé: Birth of a Legend, which focused on his childhood, and a 2021 Netflix documentary looked at his life from 1958-70, when he went from young superstar to national hero.

From left: Pelé appeared on ‘The Mike Douglas Show’ in 1978 with the host and Jerry Lewis.

Everett

He was born Edson Arantes do Nascimento (named after Thomas Edison) on Oct. 23, 1940, in the small town of Tres Coracoes in the state of Minas Gerais in Brazil. Everyone called him Dico until the nickname Pelé came to him as a boy, though he admits he’s unsure why his playmates began to call him that. His father made a meager living as a professional footballer who never quite recovered from a serious knee injury, and his mother, for a long while, insisted that her son choose a different, more stable profession.

“Mother wasn’t too pleased by my constant attention to football. She put it in the same category as bank robbery,” wrote Pelé, who at first dreamed of becoming an aviator.

As a boy, he filled his days playing soccer barefoot with other children. “We would stuff the largest man’s sock we could find with rags or crumpled-up newspaper, roll it into as close a ball shape as we could manage and tie it around with string,” he wrote. “Brazilians learn to kick as soon as they learn to stand up; walking comes later.”

At age 7 he began shining shoes, sometimes at the Bauru Athletic Club, where his father played. Most of the money he earned went to the household, though he admits holding back a bit of it so he could attend a movie occasionally. When his dad finally succeeded in finding a second job — an aide in a health clinic — Pelé helped him by emptying bedpans and making coffee while his dad regaled him with tales of the famous soccer players he knew before his injury. “His love of the game came through in every word he uttered,” Pelé wrote.

He and his friends eventually created a soccer club and raised money for a ball and uniforms by collecting and selling soccer cards, stacking firewood and rolling fresh cigarettes from discarded butts they would find. When the gang was desperate, they sold peanuts they stole from a railcar, but this activity led to tragedy when one of the team members was killed in a mudslide near a cave where the team hid its stolen nuts. They named themselves the September 7th Club, honoring both Brazil’s Independence Day and the name of a street they played near, but they preferred their nickname, the Shoeless Ones, and Pelé writes that he doesn’t recall them ever losing a serious game.

When he accepted a cigarette from a friend, his father chided him for taking charity and he told his son that if he intended to smoke he should ask the family for enough money to do so, and Pelé never touched another cigarette. When he got drunk on wine, he got sick and his father spanked him, and he swore off liquor. As an adult, Pelé was overwhelmed with offers to endorse products — so many that he became soccer’s first millionaire — but never accepted offers to promote cigarettes or liquor.

When he was 12, his soccer got a serious boost when the mayor of Bauru created a youth tournament that pitted neighborhood teams against one another, but participants were required to wear shoes. A man with three sons on Pelé’s team agreed to supply the boys used shoes in exchange for being allowed to coach them and rename the team, “Ameriquinha,” which, in Portugese, means “Little America.” The final game of the tournament was played at BAC Stadium, where his father played his professional games. The stadium was packed to capacity with 5,000 fans, and Ameriquinha took first place. Some fans, as is tradition, threw coins onto the field, which were given to Pelé, the smallest member of his team, because he was the leading scorer. His mother, though, made Pelé share the money with his teammates.

Ameriquinha’s coach moved from the city when Pelé was 13 and the team disbanded, but BAC was starting a juvenile team and it invited him to join. Valdemar de Brito, a former World Cup player, was hired to coach, and it was the first time Pelé was afforded new shoes. The coach permitted no swearing or arguing, even off the field, and asked his players to stop reading the local newspaper because it was publishing stories about the team and he feared that reading them would turn his players into “prima donnas.”

Valdemar de Brito taught Pelé to kick a ball so it would curve and also the famous “bicicleta” — the “bicycle kick,” which Pelé called “a beautiful thing to see” even though he recalled later that he used it to score a goal only about five times in his career. He joined an additional club at age 14, and at that age he was offered a tryout with the Bangu Club, a pro team larger than the one on which his father played. His mother, though, wouldn’t allow it because making the team would have involved Pelé moving to Rio de Janiero.

A year later, the Santos Football Club made him a similar offer, and this time his mother acquiesced. His parents bought him the first pair of long pants he ever owned and shipped him off to Vila Belmiro, where — after two failed attempts at sneaking back home because he feared he was too young and too small to compete — he settled into roles with the Santos Juvenile and Infantile teams, though he trained with the “first team.” Still underage in 1956, he was already under contract — technically illegal — with Santos and earning the equivalent of $60 per month.

His debut with the Santos Club first team was during a “friendship” game against Cubatao. Santos won 6-1 and Pelé scored four goals. The first time he scored in a game that counted was, ironically, on Sept. 7. It was 1956 and he was 15. At age 16, he got a 20 percent raise and signed a legal contract with Santos. Shortly thereafter, Pelé played for Santos in the Maracana Tournament in the nation’s capital in front of the largest crowd he had ever seen in his life, and he scored three goals. A year later, he was playing in the World Cup tournament, where he became the youngest player ever to score, at 17 years and 239 days old.

So legendary was Pelé’s ability to score that goalkeepers would often wave or bow at him after he’d beaten them, as if it were an honor to have been scored on by the great one. If a goalkeeper stopped a particularly good shot of his, Pelé would stop and shake his hand, and such displays of sportsmanship enhanced his already enormous reputation.

Pelé played his last game for Brazil in 1971 when 180,000 fans shouted in unison, “Fica! Fica!” [“Stay! Stay!”] In 1974, he attended the World Cup not as a player but as a TV commentator.

Pelé scored 400 goals for Santos before he even turned 20, even though he was often double- or triple-teamed by defenders, and Santos won 11 league championships during his tenure. On Oct. 2, 1974, at the 20-minute mark during his final game with Santos, he caught the ball with his hands in mid-play, placed it in the center of the field, knelt down and raised his arms, tears streaming down his face. The crowd roared, and Pelé disappeared into the stadium’s tunnel.

The gesture signaled his retirement from the game he loved, but a year later he signed for $1.4 million annually to play for the New York Cosmos, a team owned by Warner Communications that played in the North American Soccer League. While the NASL was not very popular, Pelé’s debut game with the team was broadcast by CBS to dozens of countries.

Fans unfurled a banner wishing Pelé well during the World Cup match between Brazil and South Korea on Dec. 5 in Doha, Qatar.

Francois Nel/Getty Images

Pelé played his last professional game on Oct. 1, 1977, an exhibition match between the Cosmos and Santos, where he played half the match on one team and the other half on the other in front of a capacity crowd at Giants Stadium in East Rutherford, N.J. The game was televised on ABC’s Wide World of Sports.

After two years with the Cosmos, Pelé wrote: “I believe the success of soccer in the U.S. is inevitable. Nor do I think it will come about at the expense of some other sport, such as baseball or American football, or hockey or any other sport; in fact, I feel it would be a major mistake to attempt to take fans from any other sport to support soccer. Soccer will be successful on its own.”

Indeed, youth soccer has become one of the biggest participation sports in the country since Pelé’s prediction, and viewership for pro soccer exploded in the U.S. in 2014, with 18.2 million viewers tuning in to see the U.S. play Germany in the World Cup.

Pelé began endorsing products shortly after his 1958 World Cup debut, beginning with a $1,000 deal to hawk Tetra-Pak’d milk. In 2014, his contracts totaled $73 million to endorse Volkswagen, Hublot watches, Emirates Airlines, Subway sandwiches and more, according to Sports Illustrated.

What set Pelé apart from Maradona and current soccer stars Lionel Messi and Cristiano Ronaldo, wrote SI‘s S.L. Price, “was that quality of kinetic joy. Every run and goal, all 1,283 of them, seemed to signal his thrill at being alive.”