The COVID-19 pandemic and other U.S. efforts to stop asylum access significantly impacted immigration policy and enforcement in the United States in 2022.

In various reports, U.S. border officials and immigration advocates say border numbers reflect the deteriorating economic and political conditions in some countries that drive people to come to the southern border of the U.S.

One of the most talked about guidelines is Title 42, a public health policy that allows for immediate expulsion of migrants during public health emergencies. It was put in place under former President Donald Trump at the start of the coronavirus pandemic. President Joe Biden wants it to end by December 31.

“We need to recognize that, first of all, the justification for the policy no longer exists,” said Nicolas Palazzo, an immigration attorney at Las Americas Immigration Advocacy Center and border fellow at the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society. “The policy was implemented at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic and it was used as a means of properly containing transmission of the virus.”

Palazzo, who works directly with detained and non-detained migrants, said border policy has historically been mostly directed by executive action.

“Because Congress has failed to come together to actually legislate a policy proposal around immigration,” he told VOA, “and because you rely on executive action to dictate border policy, it creates this ad hoc way of enacting policy because it changes during each administration and gives the [U.S.] president unilateral power to essentially change what’s happening on the ground.”

Title 42 was expected to end on December 21 after a federal judge in Washington ordered enforcement of it to end.

But conservative-leaning states appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court, arguing that ending Title 42 would cause “irreparable harm” because they would be expected to spend resources on law enforcement, education, and other services to assist newly arrived migrants.

Chief Justice John Roberts granted a temporary stay pending a response by the Biden administration.

On Tuesday, the Biden administration urged the court to deny the request by 19 Republican-led states to keep in place Title 42 restrictions at the U.S.-Mexico border. It also asked for an extra week before the guideline is lifted to allow for an “orderly transition to Title 8 operations.”

Relying on Title 8

Title 8 is the immigration code adopted by Congress that deals with immigration and nationality.

Under Title 8, those arriving at the border without documents or trying to enter between ports of entry can be removed without their case being decided by an immigration court. However, if a migrant wants to claim asylum, they are interviewed by an asylum officer before removal or deportation.

Federal law allows people from other countries to seek asylum in the U.S. if they fear persecution at home. They must be present in the U.S. and prove a fear of persecution.

Immigration experts explained that Title 8 has always been in use at the border, even during the pandemic.

According to U.S. Customs and Border Patrol (CBP) data, 1,299,437 migrants were processed under Title 8 in fiscal 2022. That means they were either expeditiously removed without their case being decided by an immigration court or allowed entry into the U.S. after passing a credible-fear screening by the asylum officer and can continue their case in immigration courts where they apply for asylum as a defense against being deported.

If the migrant doesn’t pass the credible-fear screening or their case is denied in immigration court, they are removed from the U.S. If they try to return without documents, the penalties could be higher, including prosecution under criminal law and getting barred from applying for any legal immigration visa in the future.

In May, after the administration’s initial attempt to end Title 42, VOA spoke with Luis Miranda, a CBP spokesperson, who said officials were preparing to “simply go back to processing any encounters across the border the way we always have under Title 8, which is the immigration authority that has always been in place throughout the history of U.S. Customs and Border Protection.”

Miranda said the U.S. government was expecting arrivals to increase at the southern border but added that those unable to establish a legal basis to remain in the U.S. will be removed.

“We’ve been planning for that,” he said. “And to process any encounters effectively and humanely. But ultimately, if someone is trying to come in without legal authorization and doesn’t have the legal basis to stay, they will be placed in removal proceedings.”

Besides Title 8, the U.S. Department of Homeland Security in mid-December announced it is executing plans to manage an increased flow of migrants at the U.S.-Mexico border, including a new process for Venezuelan asylum-seekers who meet certain requirements to fly directly to the U.S. and stop them from making the journey to the Southwestern border by land.

U.S. immigration officials also requested more border patrol agents in their fiscal 2023 budget while also increasing the use of CBP One, a mobile application where asylum-seekers can submit documentation and schedule appointments at ports of entry.

The Biden administration also said it has streamlined the border process to quickly refer for prosecution any individuals who “evade apprehension,” are “repeat offenders,” or “engage in smuggling efforts.”

Demographics at the border

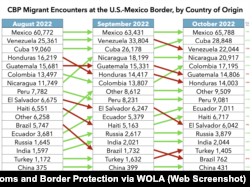

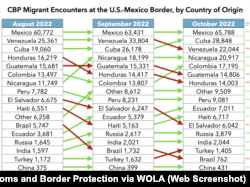

A November analysis by the Washington Office on Latin America (WOLA), a D.C.-based human rights organization, shows that until recently, Mexico was “nearly always the number-one country of origin for migrants at the U.S.-Mexico border. Until 2012, more than 85% of migrants apprehended by Border Patrol were Mexican citizens. By 2019, that had fallen to 20%.”

WOLA also shows that Cuban migrants at the border increased significantly after the Nicaraguan government in November 2021 eliminated visa requirements for Cubans, which in return made it less complicated for them to travel to the U.S.-Mexico border.

“Mexico does not allow U.S. authorities to expel Cubans across the land border under Title 42, and Cuba has not permitted U.S. expulsion flights; 98 percent of Cubans apprehended at the border in 2022 were processed in the United States under normal immigration law,” according to WOLA.

Under the Cuban Adjustment Act, passed in 1996, Cuban migrants will be allowed to apply for permanent resident status after a year in the United States. In November, the Cuban government agreed to once again accept U.S. deportation flights.

Other nations that saw increased arrivals at the U.S.-Mexico border in 2022: Venezuela, Nicaragua, Colombia, Haiti, China, and Turkey, among others.

Title 42 has been used in most encounters since March 2020. For the fiscal year 2022, however, the data indicates 1,079,507 were expelled and 1,299,437 were processed under Title 8 authority.

Not every encounter under Title 42 represents a unique person, as some migrants have tried to cross multiple times.

So far in fiscal 2023, which began October 1, U.S. border officials have registered 230,678 migrant encounters. Of those, 78,477 were expelled, which means they were sent back to Mexico under Title 42 without legal consequences. The rest were either detained, allowed to seek asylum, given humanitarian parole, or swiftly deported, meaning they were formally processed for expedited removal.

What is currently happening at the border?

With the imminent ending of Title 42, thousands of migrants have been lining up to present themselves to a border patrol officer — a development that had been anticipated by federal government officials, immigration advocates, and border nonprofits.

Migrant advocates in Reynosa, Mexico, told VOA that about 750 migrants a day have arrived over the last few days.

Hector Silva, a pastor in the area who also operates one of the largest migrant shelters south of the border, Senda de Vida, or “Path of Life,” told VOA that advocates and volunteers have been helping about 14,000 families in the last few weeks.

“We have seen in past years that people get encouraged to come and then they do not know where to go,” Silva said in Spanish.

“And what is happening right now from Tijuana to Matamoros is that people are waiting, and they have been waiting for months. [Some] have been waiting for years. And we tell them one thing: do not risk yourselves. Do not come without knowing what you will face at the border.”