Australia’s new leader signaled Tuesday that he would resist growing Chinese influence in the Indo-Pacific region — seeming to dismiss Beijing’s hopeful comments upon his election and portending a growing closeness between the United States and Australia.

“We will determine our own values,” newly elected Prime Minister Anthony Albanese said Tuesday, on the sidelines of a meeting of leaders of the Quad, an informal grouping of the United States, Japan, India and Australia. “We will determine Australia’s future direction. It’s China that’s changed, not Australia.”

He added that he had received a formal congratulatory note from Chinese Premier Li Keqiang but had not spoken to Beijing since his election win, three days earlier.

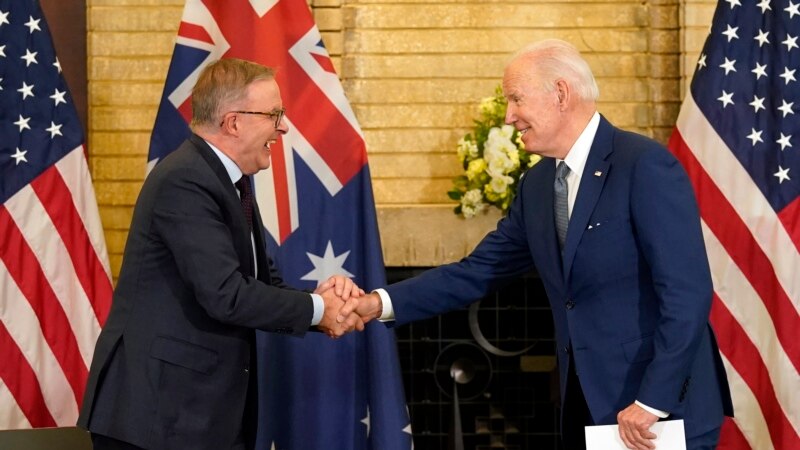

Also on Tuesday, the White House said in a statement that President Joe Biden “reaffirmed his steadfast support for the U.S.-Australia alliance and commitment to strengthening it further.”

Biden’s statement also alluded to China’s increased interest in the island of Taiwan, which Beijing says is part of China, saying that the U.S. president “commended Australia’s strong support for Ukraine since Russia’s invasion, and the leaders agreed on the importance of continued solidarity, including to ensure that no such event is ever repeated in the Indo-Pacific.”

Albanese, a left-leaning politician from Australia’s Labor Party, pledged that if elected, he would deepen relations with the Quad and with the U.S. In his initial comments as prime minister, he described the U.S. as Australia’s “most important ally.”

Albanese also said the four Quad leaders discussed China’s increasing boldness in the Asia-Pacific region, including how to “make sure that we push our shared values in the region at a time when China is clearly seeking to exert more influence.”

Albanese’s election came after nine years of declining Sino-Australian relations under conservative Prime Minister Scott Morrison. The relations took a further downward turn in 2021, when Chinese officials handed an Australian journalist a list of 14 grievances that Beijing allegedly had with Canberra.

The list included Australia’s foreign interference laws, decisions to ban Chinese provider Huawei from its 5G network, and siding with the U.S. “anti-China campaign” by calling for an inquiry into the origins of COVID-19.

In September, the U.S. announced a trilateral security partnership named “AUKUS” — for Australia, the United Kingdom and the United States. That agreement included the unprecedented decision to share U.S. nuclear submarine technology with Australia, a move widely seen as a bulwark against Chinese aggression in the Pacific. As a candidate, Albanese pledged to support the AUKUS deal.

Then in April, China inked a security deal with the Solomon Islands that would allow China to “make ship visits to, carry out logistical replacement in, and have stopover and transition in the Solomon Islands” — language that raised concerns in Canberra and Washington over Beijing’s possible ambitions in the Pacific.

Peter Jennings, executive director of the Australian Strategic Policy Institute, said this week that Australia has long ignored the “threat from the east that can watch and potentially target our military bases.”

“For decades we have over-estimated our influence in the Pacific; under-invested in promoting our security; and failed to appreciate China’s strategic intent,” he said in a column in The Australian, the nation’s largest national newspaper.

And former Prime Minister Kevin Rudd — a self-professed Sinophile who speaks Mandarin and who named Albanese as his deputy prime minister during his term — encouraged the new prime minister to work multilaterally to counter Beijing.

“A successful China strategy should be non-negotiable on our core values: our liberal democracy, our commitment to universal human rights and our alliance with the United States are not up for debate,” he wrote. “But we should talk less, do more, and — when we inevitably disagree with Beijing — we should always hunt in packs so that Australia cannot be easily singled out for retribution.”

Charles Edel, Australia chair at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, told journalists ahead of the summit that Australia has a front-row seat to China’s broader ambitions.

“Things have changed enormously across the region, and nowhere is that more true than in Australia, which has recently really been at the front of the pack on so many foreign policy and domestic decisions affecting relations with China,” he said.

But for all of this talk around and about China, a carefully worded Tuesday statement from the four Quad leaders strenuously avoided the mention of the country’s name.

“We strongly oppose any coercive, provocative or unilateral actions that seek to change the status quo and increase tensions in the area, such as the militarisation of disputed features, the dangerous use of coast guard vessels and maritime militia and efforts to disrupt other countries’ offshore resource exploitation activities,” it said.