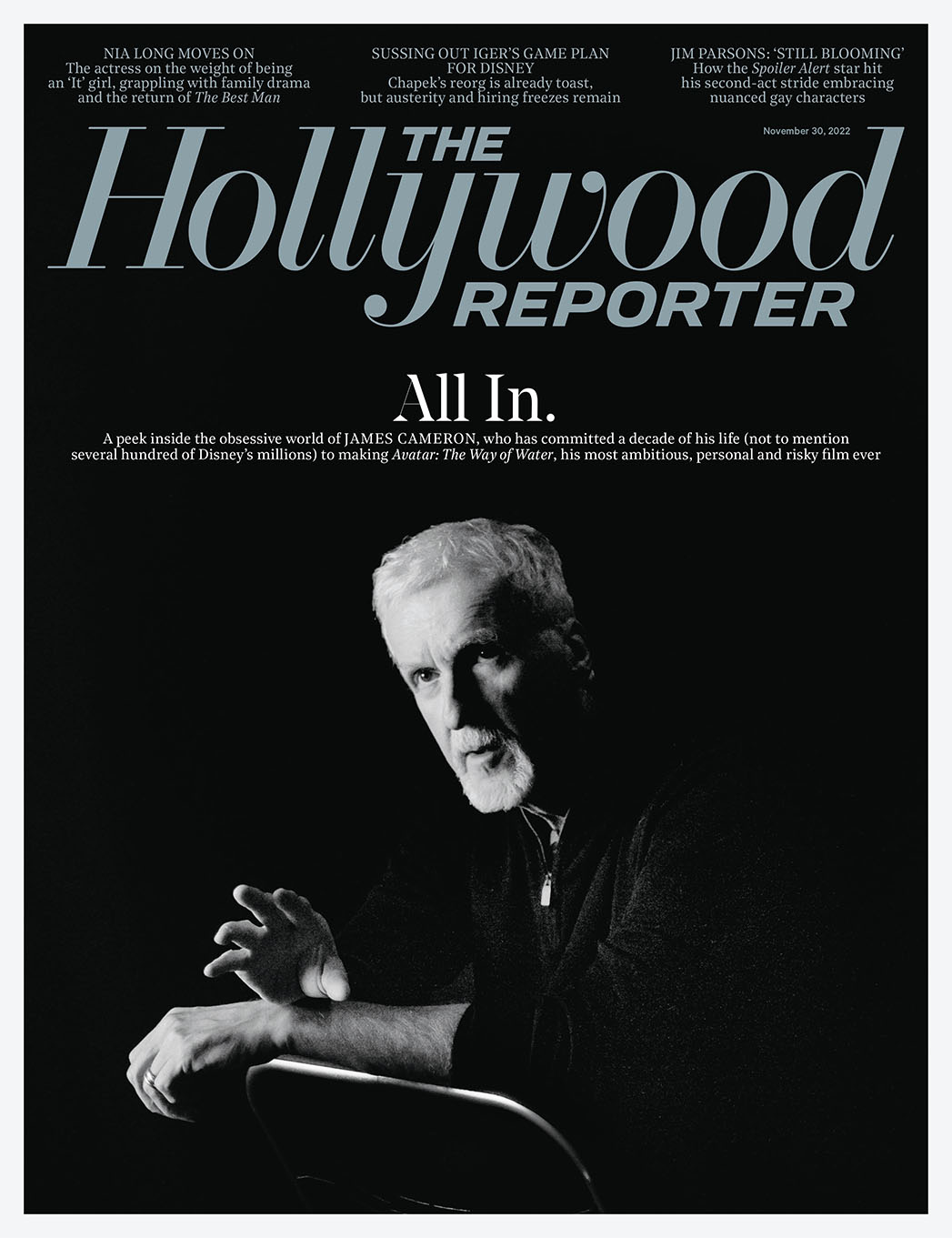

Photographed By Niki Boon

A few years ago, after James Cameron finished the first Avatar film, his kids called a family meeting to deliver some notes on his parenting. Some of the kids, who today range in age from 15 to 32, had attended the MUSE school in Calabasas that Cameron’s wife, Suzy Amis Cameron, founded in 2006. At MUSE, students are encouraged to provide feedback to their teachers, and now the Cameron brood was emboldened to apply that same technique at home.

Cameron is known in the film business for getting what he wants when he wants it, from release dates to budgets to the right to mount elaborate oceanic expeditions on a studio’s dime. The director admits he has sometimes brought his hard-driving style home, and there are moments when his fathering has resembled the Robert Duvall character in The Great Santini, the relentless Marine colonel patriarch. “I’m on a rules-based universe, and the kids weren’t into it,” Cameron says. “They said, ‘You’re never around half the time. And, then, when you come home, you try to make up for it by telling us all what to do. And Mom’s really the one that’s been making all the rules the whole time while you’ve been off shooting. So you don’t get to come home and do that.’” (The Camerons have three children together and one each from a previous marriage — his to Linda Hamilton, hers to Sam Robards.)

Photographed By Niki Boon

Cameron says he took the kids’ note, that he tries to listen more and control less. “I thought, ‘Well, that’s valid,’” he says. “I realized I was wearing the mantle of responsibility of a parent and overcompensating for the time I wasn’t there.”

Perhaps more than any new camera system or giant media merger, the humbling experience of parenting teenagers has had the greatest impact on how Cameron made his latest movie, both in the choice of subject matter and in the way he managed his cast and crew.

In Avatar: The Way of Water, which Disney will release Dec. 16, Cameron takes the stakes to the home— albeit an alien home, where Mom and Dad are blue and 9 feet tall. “I thought, ‘I’m going to work out a lot of my stuff, artistically, that I’ve gone through as a parent of five kids,’” Cameron says. “The overarching idea is, the family is the fortress. It’s our greatest weakness and our greatest strength. I thought, ‘I can write the hell out of this. I know what it is to be the asshole dad.’”

The Way of Water is Cameron’s first film in 13 years, since the original Avatar became the highest-grossing movie of all time ($2.92 billion worldwide), collected nine Oscar nominations, including best picture and best director, and introduced groundbreaking new filmmaking techniques. The sequel cost more than $350 million, and it’s scheduled to kick off a wave of three more Avatar movies, which, if completed, will represent a more than $1 billion investment for Disney on production costs alone.

It’s early November, and Cameron is at Park Road Post Production, Peter Jackson’s art deco-style facility in Miramar, a suburb of Wellington, the windswept capital of New Zealand that has become a low-key Hollywood Down Under since Jackson filmed the Lord of the Rings movies here in the early 2000s. Those fantasy films are so central to Wellington’s modern identity that a giant sculpture of Smaug the Dragon greets travelers at the Wellington airport. Cameron is at work on what he hopes will be Wellington’s next great epic, in an office that was once Jackson’s, a stately, wood-paneled room that he has made his own with some stacks of books — Kim Stanley Robinson’s climate change science fiction novel The Ministry of the Future is on top — and a mini-fridge stocked with vegan snacks (he’s been vegan for more than a decade).

Cameron is shuttling between the mixing theaters where the crew is tweaking the sound on the last four of 15 reels — Avatar: The Way of Water will run just over three hours — and a dark nearby visual effects office that he ducks into to oversee the last 60 or so of the movie’s jaw-dropping 3,350 visual effects shots. At 68, the director looks pretty much like he did on the first Avatar movie. He’s still lean, still wears a motocross jersey and jeans on set, and still focuses so intently on whatever he’s doing at the moment that his crew plays an “awoogah” sound effect of a submarine-style diving klaxon on speakers to get his attention. “I don’t even respond unless they do the ‘awoogah,’” he says.

The first Avatar followed paralyzed Marine Jake Sully, played by Sam Worthington, who takes on an avatar body to travel to the lush planet of Pandora, inhabited by the indigenous Na’vi people, and gets enlisted in a scheme to strip the planet of its precious resource, unobtanium. In the new film, which travels to Pandora’s oceans, Jake is a father and husband to Na’vi princess Neytiri (Zoe Saldaña). Their kids include a teenage Na’vi daughter played, thanks to the magic of visual effects, by Sigourney Weaver, 73, and an adoptive human son, Spider, played by Jack Champion, who is now 18 but was 13 when the film started shooting. Kate Winslet plays a character from another ocean-bound Na’vi clan. Cameron has already shot Avatar 3, due in 2024, and part of 4 (2026), and he has a script for 5 (2028). “It’s all written out, stem to stern, four scripts, and fully designed,” Cameron says. “We know exactly where we’re going, if we get the opportunity to do it. And that opportunity will simply be market-driven, if people want it, if they like this movie enough.”

Photographed By Niki Boon

Amid the studio’s massive financial outlay and his own commitment of years in the prime of his career, Cameron is aware that the Avatar franchise has its doubters. “There’s skepticism in the marketplace around, ‘Oh, did it ever make any real cultural impact?’” he says. ” ‘Can anybody even remember the characters’ names?’” If people are less likely to remember Jake Sully than, say, Luke Skywalker, that’s partly because Avatar is only one movie into its mythology, Cameron says. “When you have extraordinary success, you come back within the next three years,” he says. “That’s just how the industry works. You come back to the well, and you build that cultural impact over time. Marvel had maybe 26 movies to build out a universe, with the characters cross-pollinating. So it’s an irrelevant argument. We’ll see what happens after this film.”

When the first Avatar exploded at the box office in 2009, Cameron’s then-home studio, 20th Century Fox, was eager for an immediate follow-up. “I was actually the one putting the brakes on it and saying, ‘I don’t know if I want to go down this road again,’” Cameron says. Because of the outsized performance of the original, “we have to, literally, be in the top five grossing films in history to succeed. That’s a silly target.” At the time, Cameron was more interested in pursuing his other passions, including ocean exploration and environmental sustainability. “Being away and going in his submarines connects him back to the earth,” Worthington says. “It relaxes him.” In 2012, tucked inside the 43-inch-wide cockpit of a submarine he designed with the National Geographic Society, Cameron became the first person to complete a solo dive to the Mariana Trench, the deepest point in the world’s oceans. “I started confronting this issue of, ‘Do I even want to make another movie, let alone another Avatar movie?’” Cameron says. “Because I was having so much fun.”

Cameron’s environmentalism goes well beyond the Hollywood standard — drive a high-end electric vehicle, write a check. He drives a 2013 Kia Rio because he says a small quality used car has less of a carbon footprint than a new electric car. He has sold his two houses in L.A., and his family now splits time between what he describes as a “comparably modest” home in Wellington and a 5,000-acre farm about 20 miles away that grows hemp and organic vegetables. He’s also invested in agricultural land and a manufacturing facility in Saskatchewan, Canada, to make pea protein for vegan foods, and has executive produced a documentary, The Game Changers, about athletes with plant-based diets. “I don’t define success and wealth as things, but as experiences between people and between us and nature and places — things that really feed you,” he says.

Cameron believes most of us are suffering from what he calls “nature deficit disorder,” that our indoor, screen-bound, urban lifestyles have left us easily distracted and disconnected from our senses. Part of what convinced him to get back behind the camera was the potential he saw for his movies to impact the audience’s relationship with the environment. As he points out, “Avatar is the highest-grossing film, and it’s a movie that’s asking you to cry for a tree.” Audiences in 2022 are even more attuned to those themes and potentially more anxious about them. “You can’t hit environmental messaging over the head,” Cameron says. “People are angsty enough. We’ll be injecting this film into a marketplace in a different time. And maybe things that were over the horizon in 2009 are upon us now. Maybe it’s not entertainment anymore.” Avatar: The Way of Water, Cameron says, is not intended to make people fear climate change but to suggest, by way of choices made by the film’s Na’vi characters, some alternate paths forward. “We skipped from complete denial [of climate change] to fatalistic acceptance, and we missed the middle step,” he says. “The filmmaker’s role is not to make it all gloom and doom anymore but to offer constructive solutions.”

Courtesy of Mark Fellman20th Century Studios

***

“This looks like a 1960s dinosaur movie explosion.” Cameron is huddled in a small, dark office next to his own, reviewing a sequence of a helicopter crash with his visual effects supervisor, Eric Saindon, and a group of Weta FX artists participating by Zoom. During the workday, Saindon puts the shots that are ready for approval up on a monitor that’s visible as Cameron walks back to his office from the sound mixing stage, to serve as what the crew calls “director bait.”

Some 1,400 Weta artists are working on The Way of Water, but to be the one in charge of the helicopter crash is a particular burden. Cameron flies helicopters himself and puts them in most of his movies — he had a stunt pilot fly one under a freeway overpass in Terminator 2, dangled Jamie Lee Curtis out of one in True Lies and designed a futuristic helicopter that could actually fly for the first Avatar. There is probably no tougher audience on earth for a CGI helicopter crash scene than Cameron, and he wants a lot more from this one before he’ll approve it. “I’d love to see a couple more frames of the crumple,” he says. “Get with your destruction guys. I’d love to see the tail fin come flying out at me as it detaches. Give it some rotational movement. It just looks like it falls off and goes, ‘Eh.’”

Mark Fellman/20th Century Studios

Cameron’s shot critiques are direct and specific, but “anyone can give me shit,” he says. Weaver, for instance, says she objected to the initial design of her character, which she described as “too neat and pretty,” and instead successfully advocated for a more awkward teenager. Weaver’s character, scientist Grace Augustine, died in the first Avatar, but “the idea for Kiri came from, well, is Grace really dead?” Cameron says. “I thought, hang on, there’s this avatar. What could I do with the idea of bringing Sigourney back, playing a kid? It was just a fun idea. I couldn’t get it out of my head.” As at home, Cameron says he has also changed his leadership style at work. “I try to be more emotionally present for the crew and use more humor,” he says. Cameron loves New Zealand crews, which he says are less hierarchical than crews in the U.S. or England, more likely to shout, “Hey, Jim,” in the hall than to be deferential. “Here, everybody’s counted equal,” he says. “You have a job to do, but just because you have that job doesn’t make you better. I love that about this place. I wanted my kids to grow up in that environment, to not be, as they call it, ‘bougie,’ but what they mean is, ‘entitled.’” Cameron, who was born in Canada and retains his Canadian citizenship, is in the process of applying for New Zealand citizenship.

After the first Avatar, Cameron and his producer Jon Landau determined that Cameron was too much of a bottleneck because every virtual camera shot went through his hands. On The Way of Water, Cameron estimates that he shot 70 percent of the virtual camerawork, and Richard Baneham, an Irish visual effects supervisor who worked on the first Avatar, shot the other 30 percent. “That’s big growth for me,” Cameron says. Weaver, who first worked with Cameron on 1986’s Aliens, calls him “a much more relaxed director. … He’s making this dream of his, this saga, come true,” Weaver says. “He’s still driven, but it’s much warmer colors.”

Courtesy of Mark Fellman20th Century Studios

Cameron’s collaborators accept his intensity because it pays off, spectacularly. Of the 10 highest-grossing movies of all time, only two of them — Avatar and Titanic — were not based on preexisting intellectual properties like comic books, novels or prior films. With the studio’s appetite for more Avatar, Cameron felt he had an opportunity to go bigger, in a storytelling sense, than he ever had. “I want to tell an epic story over a number of films. Let’s paint on a bigger canvas. Let’s plan it that way. Let’s do The Lord of the Rings. Of course, they had the books. I had to write the book first, which isn’t a book, it’s a script.”

In the fall of 2010, Cameron committed to make what was then going to be two more Avatar movies, with the unusual deal provision that Fox would co-fund, with Cameron, a nonprofit, the Avatar Foundation, to support Indigenous rights and the environment. Fox triumphantly announced a release date for the first sequel: December 2014. “I never really believed in any of the dates that they amused themselves by announcing,” Cameron says. After he returned from the Mariana Trench in 2012, Cameron started to think seriously about the movies, spending the first several months just jotting down notes — ideas for creatures, cultures, themes. Inspired by the experience he had producing the early 2000s sci-fi TV show for Fox, Dark Angel, he convened a TV-style writers room in mid-2013. “I walked in on day one and plopped down 800 pages of notes and said, ‘Do your homework, and we’ll meet next week.’” Eventually, he handed writing duties for Avatar 2 to Rick Jaffa and Amanda Silver, the married screenwriting duo behind the successful reboot of the Planet of the Apes series, with whom he shares screenplay credit. Ultimately, the writing process, which included finishing all four scripts before calling “action” on anything, took four years. Cameron finally started production on Avatar 2 in September 2017.

Courtesy of 20th Century Studios

Just three months after Cameron started shooting, Pandora suddenly found itself under new ownership, when Disney bought Fox for $71.3 billion. In some ways, Disney was an ideal home — the studio had already spent $500 million on a Pandora attraction at its theme park in Florida, and so was invested in Avatar succeeding. Disney was also moving in the direction of releasing fewer films theatrically, but bigger ones, the spectacle-driven kind Cameron is uniquely equipped to make. And Cameron and Disney had been flirting for years: Back in 2005, when Fox was wavering over whether to greenlight the first Avatar, Cameron and Landau had invited then-CEO Bob Iger, studio chief Dick Cook and CFO Alan Bergman to their soundstage in Playa Vista to watch some test footage. “We walked out of that and we said, ‘We have to have it,’” says Bergman, now chairman of Disney Studios Content. “Sitting there in that screening room, I’d never seen anything like it. The world, Jake’s character. It was so unique.” Disney started negotiations to make Avatar, which sparked Fox to convince its financial partners to raise their investments in the film, and ultimately Cameron stayed at the studio he had been in the trenches with for decades, on Titanic, True Lies and Aliens. In March 2019, when the Disney/Fox deal closed, one of the first things Bergman says he did was meet with Cameron and Landau. “I said, ‘See, Jim, we had to buy the company to get the next Avatar.’”

Four and a half weeks before The Way of Water‘s release, Disney delivered another shock, abruptly firing CEO Bob Chapek and reinstating Iger. The move came as a surprise to almost everyone in Hollywood, including the team working away in Wellington, although the news was not unwelcome. “Bob Iger was part of wooing us in the beginning,” Landau says. “He saw a value in Avatar across the company. We’re big fans.”

On Titanic and the first Avatar, Cameron clashed with Fox execs over budgets and the films’ potential to earn them back. But his relationship with Disney has, so far, been a smooth one. “Maybe it’s still a honeymoon phase,” Cameron says. “I don’t know. We’ll see. If the movie doesn’t make money, then, maybe, the honeymoon’s over.” He cites his transparency, telling the studio early on if he feels something may shift in the schedule, and says he respects Disney’s marketing prowess. It may also be that his era of F-bomb-laden shouting matches with executives is behind him. “A lot of things I did earlier, I wouldn’t do — career-wise and just risks that you take as a wild, testosterone-poisoned young man,” he says, declining to specify further. “I always think of [testosterone] as a toxin that you have to slowly work out of your system.”

TIMOTHY A. CLARY/AFP via Getty Images

Landau, who as a young Fox executive first met Cameron while working on True Lies, has been his producer and right hand since Titanic. If one of Cameron’s superpowers is the depth of his focus, that focus is partly made possible because Landau is somewhere nearby, with one Airpod sticking out of his ear, simultaneously having a phone conversation with Burbank about one deadline and an in-person conversation with a crewmember in Wellington about another. “I’ve seen an evolution of him,” Landau says of Cameron. “Jim learns from every one of his experiences. He looks back and goes, ‘This is what worked, this is what didn’t work, how do I make it better?’” As Landau is in the middle of this sentence, there’s a hard knock on his office door and Cameron pops in, Kramer-style. “Did he tell you we’re like an old married couple?” Cameron says. “I don’t want to say nice things in front of him — it’ll go to his head — but I feel like there’s no problem we can’t solve.”

Photographed By Niki Boon

The Avatar production certainly presented its share. For one thing, the shooting schedule on the Avatar films is so unusually long that crewmembers talk about their “Avatar-versaries.” The human characters in the movie, like Champion’s and a marine biologist played by New Zealand actor Jemaine Clement, are shot in live-action. The actors playing Na’vi characters, like Worthington and Weaver, are shot in performance-capture, on stages where cameras track their movements and, later, visual effects artists modify their appearance. This is how the character of Kiri manages to look recognizably like Weaver and like a teenage alien at the same time.

Huge chunks of the story take place underwater, and several castmembers had to learn to free dive to meet Cameron’s standard of realism. Weaver, who had observed classes at Laguardia High School to create the role of Kiri, needed her awkward character to finally find her comfort zone in the ocean. “I thought, ‘How am I going to get to that place of confidence and certainty when I’m underwater?’” Weaver says. “We work really hard trying to do these scenes, which are complicated and also delicate.” Water scenes aren’t just harder for the actors, they’re devilish for the effects artists. “Water, I wouldn’t say we perfected it. I think we fought it to a draw,” Cameron says. “Between waves and transparency and aeration and foam and spray and drips and shedding and splashing. It’s a layer on a layer on a layer of finer and finer simulations. It’s insane, actually.”

Courtesy of Mark Fellman20th Century Studios

Cameron had finished the 16-month performance-capture portion of the second, third and part of the fourth Avatar films and had shot some of the live-action portions when the COVID-19 pandemic arrived. In March, New Zealand closed its borders and imposed one of the strictest lockdowns in the world, moves that were credited with containing the virus there but that derailed shooting key scenes with Champion, a teenager who was growing so quickly it would be hard to match previous shots. That spring, Cameron, who had been in the U.S. when the lockdown was imposed, wrote a letter to the New Zealand government outlining why the production fit the government’s criteria that permitted international travel and describing the COVID-19 safety precautions they would take. Their arrival would enable the work pipeline to continue and, ultimately, to keep more than 1,000 people working, including hundreds of Weta artists at home. By May, the government agreed, and Cameron, Landau and 31 other crewmembers were allowed to enter the country together on a single plane.

COVID also shrunk the theatrical marketplace into which this movie will be released. “I knew it would never come back a hundred percent,” Cameron says of theatergoing. “I don’t think it ever will. But maybe 80 percent’s enough. We’ve got less competition because everybody’s working for streaming now.” When theaters were closed during the pandemic, Cameron would get on Zoom with Steven Spielberg and Guillermo del Toro and talk about the fate of their industry. “I’d say, ‘We might be out of work, guys,’” Cameron says. “Except we’re not. I got to a fatalistic but calm place. It’s like, ‘I’ll still have a job. I can still tell stories. I’ll still get to work with actors and shoot scenes. Might not be at the scale of an Avatar movie, but, I mean, they’re doing some pretty big stuff for streaming.’”

The Way of Water is one of a number of films this holiday season with long running times, including Marvel’s Black Panther: Wakanda Forever and Paramount’s Babylon. Cameron says that was negotiated pre-Disney. “I said [to Disney], ‘You bought this from a bunch of guys at Fox who agreed to a three-hour movie,’ because that’s what we said we were going to do. We’re going to play the epic game.” Asked how audiences should time a bathroom break, Cameron says, “Any time they want. They can see the scene they missed when they come see it again.” He’s not kidding. A huge part of Cameron’s box office success on his previous films has been attributable to repeat viewing. He typically doesn’t have a massive opening weekend, à la Marvel movies, but instead holds or builds his audience over time. “We’ll know by the third weekend,” he says. “You’re not going to know by the first weekend. Titanic didn’t work that way. Avatar didn’t work that way.” Avatar, which opened to $79 million, dropped just 8 percent a week for 10 weeks.

Courtesy of 20th Century Studios

3D, a huge part of the original Avatar‘s success, remains Cameron’s preferred audience viewing format this time around as well. But it’s fallen out of favor in Hollywood. “Ironically, it’s less in-demand and more available,” he says, noting that, at the time Avatar was released, there were some 6,000 3D-enabled digital projectors worldwide; now there are roughly 110,000. Cameron attributes the drop in demand to screens that weren’t bright enough and to the poor quality of films that studios began releasing after Avatar — 2D films quickly converted to 3D in a bid for a cash grab rather than something originally created in 3D, like Avatar. There are signs audiences will still pay for 3D tickets for certain films — when Disney rereleased Avatar in September, it earned an impressive $76 million at the global box office, more than 97 percent of that from 3D. One of the surprises of the rerelease for Cameron was to learn that teens and 20-somethings, who hadn’t been old enough to see Avatar in theaters the first time around, were the audience most enthusiastic to see the movie.

With the future of the franchise already mapped out, Cameron is eager to see it through, but he recognizes the possibility that he might not. “We’ll probably finish movie three regardless because it’s all shot,” he says, figuring Disney has already spent more than $100 million of that budget. “We’d have to really crater for it not to seem like it was worth the additional investment. We’d have to leave a smoking hole in the ground. Now, hopefully, we get to tell the whole thing because five’s better than four, four’s better than three, and three’s better than two.”

He’s also got plans — should the world demand them — for Avatar 6 and 7. “I’d be 89 by then,” Cameron says. That sounds like a joke, but based on the fact that it took 25 years for him to make the first two Avatar movies, it’s pretty realistic. “Obviously, I’m not going to be able to make Avatar movies indefinitely, the amount of energy required.” He’s started giving some thought to a succession plan. “I would have to train somebody how to do this because, I don’t care how smart you are as a director, you don’t know how to do this.” He figures he may have five or six more movies in him and that three of them, probably, would be Avatar movies.

Tibrina Hobson/Getty Images

He certainly seems to have enough Avatar story in his head to live in that world indefinitely — he wrote an entire script of what takes place between minute four of Avatar: The Way of Water and minute five, in which a year passes and a great deal of backstory for Champion’s character, Spider, unfolds. Cameron peeled that story off and had it turned into a graphic novel, Avatar: The High Ground, penned by YA literature writer Sherri L. Smith, which Dark Horse Comics will publish Dec. 6. At this point, he can’t see making a version of Avatar as a streaming TV show, but perhaps he could in the future. “The problem with these CG characters is that they’re so cost- and labor-intensive that it really doesn’t work for TV,” Cameron says. “Now, come back in 10 years, with a lot of machine deep learning. Insert it into our pipeline, which we hope to do, over time. We might be able to get to a TV schedule, but it doesn’t interest me right now.”

And then there’s all of that life beyond the movies that Cameron is so interested in. The submarines, the farm, the kids. “I’m not trying to build an empire here,” Cameron says. “I’m just trying to make some cool movies.”

This story first appeared in the Nov. 30 issue of The Hollywood Reporter magazine. Click here to subscribe.